The Financing Decision is a crucial decision that is to be made by the financial manager, the decision is about the financing-mix of an organization. Financing Decision is focused on the borrowing and allocation of funds required for the investment decisions of the firm.

The financing decision comes from two sources from where the funds can be raised – first is from the company’s own money, such as the share capital, retained earnings. Second is from borrowing funds from the outside the corporate in the form debenture, loan, bond, etc. The objective of the financial decision is to balance an optimum capital structure.

What are the Basic Financial Decisions?

Basic Financial Decisions that financial managers need to take: (a) Investment Decision (b) Financing Decision and (c) Dividend Decision.

Investment Decision – Also known as the Capital Budgeting Decisions. A company’s assets and resources are very rare and thus must be put to use with much analysis. A firm should pick those investments where he can gain the highest conceivable returns. Investment decision involves careful selection of the assets where funds will be invested by the corporates.

Financing Decision – Financial decision is the utmost important decision which is to be made by business individuals. These are wise decisions indeed that are to be chalked out with proper analysis. He decides when, where and how should the business acquire the fund. An organization’s increase in share is not only a sign of development for the firm but also to boost the investor’s wealth.

Dividend Decision – Dividend decisions relate to the distribution of profit that are earned by the organization. The main criteria in this decision are whether to distribute to the shareholders or to retain the earnings. Dividend decisions are affected by the earnings of the business, dependency on earnings.

What Is Corporate Finance?

Corporate finance is a subfield of finance that deals with how corporations address funding sources, capital structuring, accounting, and investment decisions.

Corporate finance is also often concerned with maximizing shareholder value through long- and short-term financial planning and implementing various strategies. Corporate finance activities range from capital investment to tax considerations.

Contents

Introduction

The Financing Decision

– Ordinary shares

– Corporate debts

– Preference shares- Convertible securities

– Trends in raising capital

– Debt Vs Equity

Capital Structure

– The effects of leverage

– Determining the optimal capital structure

Financial Decisions in a Perfect Market

– The Modiliani-Miller Theorem

– Taxes and capital structure

– Transaction costs

-Bankruptcy costs

The Stakeholder Theory

– Liquidation

– Financial distress

– Conclusion

In Summary

Introduction

In our lives, we must make numerous financial decisions. Some are minor, such as whether or not to purchase a new car. Others are significantly more significant, like whether to invest in a new business endeavor. Whatever the magnitude of the decision, it is critical to examine all of your options before making a final decision. This article has discussed some of the various types of financial decisions that you may have to make over your lifetime. It has improved your understanding of the process and how to handle each sort of decision appropriately.

After a company has made the decision to invest in an asset, whether through this through the evaluation of net present value or some other methods of evaluation (the investment decision), the company would have to decide on how to finance its investments (the financing decision).

Financial decision is the utmost important decision which is to be made by business individuals. These are wise decisions indeed that are to be chalked out with proper analysis. He decides when, where and how should the business acquire the fund. An organization’s increase in share is not only a sign of development for the firm but also to boost the investor’s wealth.

Financing can come in many forms. The company has to analyse the trade-off between the many different alternatives. Should the company use internal or external funds? If it chooses external funding, should the company raise its funds through debt, a combination of debt and equity or purely equity? In making a financing decision, the company would have to determine the optional structure for the company and be aware of the different instruments available in the market.

In this topic, we shall look at the common forms of financing, namely, ordinary shares, corporate debts, preference shares and convertible securities and discuss how a company can determine its optimal capital structure. We shall also briefly address one of the foremost theories of capital structure, the Modigliani-Miller Theorem. Finally, we shall provide an outline of the Stakeholder Theory of Capital Structure.

Objectives

(a) Provide an overview of the common forms of financing;

(b) Show how a company’s optimal capital structure can be determined

(c) Discuss the Modigliani-Miller Theorem and its implications, and

(d) Provide an overview of the Stakeholder Theory of Capital Structure

The Financing Decision

The financing decision is considered separate and independent of the investment decision and is in many ways, more complicated. In making a financing decision, the manager must know the different financial instruments and the providers of capital.

Capital markets from the area where companies that funds will come together with individuals and institutions that are willing to invest for a certain rate of return. Capital markets have grown in completely and sophistication over the years with an increasing number of instruments and players.

The financial system of a country comprises of individuals, households, institutions, corporations, financial intermediaries and the government. Financing can either be in the form of equity where investors can finance a company by buying an equity stake in it or debt, where funds are lent to those who need financing by those with excess funds.

The sources of financing discussed in this topic are not meant to be exhaustive. The increase sophistication and complexities of capital markets have brought about a bust of new innovation in instruments and sources of funding. in the following sections, we will be highlighting the salient features of four common forms of external financing.

Besides obtaining funds externally, companies can also finance their investments by using internally generated funds.

2.1 Ordinary shares

Ordinary shares are ownership claims on the company. Some of the features of ordinary shares are as follows:

(i) The maximum number of shares that can be issued by a company is its authorised share capital. The authorised share capital is specified in the company’s Articles of Association and can only be increased with the approval of the shareholders of the company Authorised shares which are issued to shareholders are called issued and paid-up share capital.

(ii) The issued shares are accounted for at par value.

(iii) When a company sells shares, any difference between the price it was subscribed at the par value is recorded in the books as share premium.

(iv) Ordinary shareholders are owners of the company and are therefore entitled to the refusal value of the company. Shareholders of the company have ultimate control of the company and they exercise this control by way of voting on the affairs of the company. shareholders can vote on general matters which are specified in the Articles of Association, including the appointment of directors,. in addition, under the Listing Requirements of Bursa Malaysia Securities Berhad, certain transaction proposed by public-listed companies would require shareholders approval, and

(v) In Malaysia, most companies would issue just class of ordinary shares. however, some companies may have more than one class of ordinary shares and shareholders of the different classes may have different voting rights. such variations are set out in the Article of Association of the company.

2.2 Corporate debts

A debt is bassially characterised by regular interest payment and an agreement to repay the principal amount according to an agreed upon schedule. unlike shareholders, lenders do not have proprietary rights to the company and hence do not have voting power. If the company defaults, lenders with collateral will have rights to the pledged assets. In the event of a winding up, lenders will have priority over shareholders in the distribution of assets. Debt can also come in many forms. They can be raised from financial intermediaries or directly from capital markets. Some major features of corporate debts (including bonds) are summarised as follows.

(i) maturity – corporate debts have fixed maturities, can be either short-term (one year or less) or long-term (more than one year).

(ii) Repayment – long-term debts are usually repaid based on an agreed upon schedule. Bonds can be repurchased and retired using internally generated funds or through funds being raised from other sources (such as proceeds from the exercise of warrants or disposal of assets). Some debt papers may carry a right to call which the company the right to repay retire the bonds prior to maturity. The call price is usually determined at the time of issue of the bond. Debt papers which carry a right to put, give the debtholder the right to sell the papers back to the company.

(iii) Security – debts can be secured by charges on landed properties, plant and equipment or other assets. It the event of default, the debtholders have the first right to the pledged assets.

(iv) Default risk – debtholders face the risk of default, i.e. the risk of the borrower falling to pay. The level of default risk will affect the credit-worthiness of the debt. There are two rating agencies in Malaysia, namely the RAM Holdings (formerly known as Rating Agency Malaysia Berhad or RAM) and Malaysian Rating Corporation Berhad (MARC), which provide rating on the creditworthiness of debt issues. Generally, a debt security is investment grade if it qualities for one of the top four ratings (i.e. RAM’s and MARC’s rating scale of AAA, AA,. A and BBB).

(v) Like listed ordinary shares, certain debt papers can be publicly traded.

(vi) interest rate – the interest rate can be either fixed or floating. In general, most corporate bonds will carry a fixed, which is determined at the time of issues. Loan agreement may sometimes incorporate a spread above a certain base interest rate, eg. the base lending rate (BLR). For example, if a corporate loan has an interest rate of 1.25% above BLR, the interest rate will change correspondingly with any change in the BLR and

(vii) When companies have investments overseas, they may choose to borrow from abroad to hedge against exposure to currency fluctuations. For some riskier investments, companies may find it easier to obtain financing from more developed equity markets that have demand for risky investments. Moreover, in some situation, the regulator may require funding to be raised overseas.

2.3 Preference shares

Preference shares are considered as hybrid security, which are legally equity in nature although they do exhibit some debt characteristics. Some common features of preference shares are:

(i) Preference shareholders receive a fixed dividend like debt but the dividend payment is at the discretion of the directors of the company. No dividends will be paid to ordinary shareholders until the preference shareholders are paid. Preference share dividends can also be cumulative, in such a situation, dividends may not be paid on ordinary shares until all past dividends have been paid on preference shares;

(ii) Preference shares do not have a final repayment date but some issues make provision for periodic retirement or redemption in accordance with section 61 of the Companies Act 1965, redemption of p[reference shares must be out of profits or proceeds from a fresh issue of shares made specifically for the purpose of redemption;

(iii) The claim of the preference shareholder on winding up ranks below that of debt holders but in priority to ordinary shareholders;

(iv) Preference shareholders are rarely given voting privileges like ordinary shareholders. The rights of preference shareholders are set out in the Memorandum and Articles of Association of the company in most cases, consent of preference shareholders must be obtained on all matters affecting the seniority of the claim; and

(v) Unlike interest, dividend paid to preference shareholders are not tax-deductible from corporate income. Preference dividends are paid out of after-tax income.

Due to their unique features, preference shares are usually treated as a third component of capital, in addition to equity and debt, in capital structure analysis and in cost of capital estimation.

2.4 Convertible securities

A convertible instrument (like convertible bonds or convertible loan stocks) can be converted into a predetermined number of other securities, usually ordinary shares in the issuing company. Some convertible give the holder the option to convert while others are mandatory converted at a specified time (e.g. irredeemable convertible unsecured loan stock). The main difference between a convertible instrument and a warrant or option is that the holder of the convertible instrument uses the value of the convertibles as consideration for conversion into the other security. Some convertible instruments give the holders the option to convert by paying partly in cash and partly by tendering the convertible instrument.

2.5 Trends in raising capital

Capital and financial markets throughout the world are undergoing changes, which could affect the company’s financing decision. There are several notable trends in capital markets that need to be considered.

Globalisation

Globalization is a term used to describe how trade and technology have made the world into a more connected and interdependent place. Globalization also captures in its scope the economic and social changes that have come about as a result.

Much has been said about globalisation and its ability to create wealth in an economy while bring about economic and financial impoverishment in others. Whatever the case may be, globalisation of capital markets is very real. Companies are now able to raise funds both in and out of the country, taking advantage of differences in taxes and regulations to lower their cost of funding. However, with globalisation, the cost of funding in different economies is expected to equalise as regulations around the world become similar and taxes associated with raising capital decline.

Globalisation has also led to the design of new finances instruments that are tailored to appeal to new sets of investors resulting in the availability of a large range of financial instruments being made available in the global capital markets.

Deregulation

Deregulation is the reduction or elimination of government power in a particular industry, usually enacted to create more competition within the industry. Over the years, the struggle between proponents of regulation and proponents of government nonintervention has shifted market conditions.

In embracing globalisation, there must also be a deregulation of economies and capital markets. This is based on the belief that the market is self-correcting and self-regulating in an ideal world, the dismantling of rules and regulations governing capital and trade flows will bring about growth in economies. However, some countries have found that free capital flows may also result in the destruction of their economies in general, capital will flow to countries where restriction are low and returns are high. As such, trends have shown that countries are finding it difficult to maintain a mighty regulated capital market as capital will flow to countries that have fewer regulations. At the same time, with deregulation, there are demands for greater transparency, higher levels of disclosures and good corporate governance.

Technology

Technology, the application of scientific knowledge to the practical aims of human life or, as it is sometimes phrased, to the change and manipulation of the human environment.

Technology has enabled the world to become a truly “borderless” world where trillions of dollars can be transacted across the globe in a fraction of time. Technology has also brought about better valuations and pricing of securities. The use of technology has allowed some markets to practice continuous 24-hour trading around the world, producing a true world market for securities.

Securitisation

Securitization is the process in which certain types of assets are pooled so that they can be repackaged into interest-bearing securities. The interest and principal payments from the assets are passed through to the purchasers of the securities.

It is the process of bundling assets that are not securities, registering the said bundles as securities and selling to investors in the United States, the five largest sectors of asset-backed securities are credit card receivables, secondary mortgage balances on home equity lines of credit, automobile loans, student loans and instalment credit issued to buyers of factory built homes. Securitisation will allow companies to sell their assets like account receivables, that were previously not marketable.

Debt vs. equity

A company which has decided to raise funds externally must decide on the type of funds to raise, i.e. debt or equity. The three main distinctions between debt and equity are summarised as follows:

(i) Debtholders have a contract specifying their claims or the company and ensuring their priority of claims over equity holders.

(ii) Interest payments to debtholders are tax-deductible expenses of the company while dividend payments to equity holders are not tax-deductible expenses and

(iii) Debt usually has a fixed maturity date, at which point the principle repayment is due, while equity has an infinite life.

Some of the risks arising from debt and equity financing are summarised as follows.

(i) Risks in debt financing

One of primary concerns in debt financing is the increased probability of bankruptcy. This happens when the company is not reasonably able repay the loan, causing it to default. While this may not necessary result in bankruptcy, default has its negative consequences, e.g. less operating and financial flexibility due to conditions imposed by the creditors.

(ii) Risks in equity financing

There are basically two main risks in raising funds through equity. The first is volatility, which can be defined as changes in the price of the share and the value of the market as a whole. Excessive volatility can make planning very difficult. For example, a company which has decided to raise funds throughout an initial public offering exercise may suddenly find that the value of the value of the market as a whole has dropped, resulting in the risk of low demand for the shares of that company. Most initial public offerings will be underwritten. However, the underwriting commission may be high if the underwriter perceives the issue to be risky in the situation, the next amount of funds raised from the offer may be much lower than expected.

Another risk in equity financing is the risk of dilution of control and earnings per share. Dilution of control occurs when a company issues new shares to non-shareholders, resulting in a dilution in the current shareholders control. Dilution of earnings reduces the EPS of the existing shares. While thre are many arguments against the reliances on EPS as a measure of corporate performance, a deterioration of EPS is still nomally negatively perceived by the market.

Like the investment decision, the financing decision also involves a risk-return trade off in order to decide on the appropriate form of financing, a company has to first assess its current capital structure and the risk and rewards of the same. Then the company has to decide whether this structure is optimal or not. The use of debt or leverage will result in higher profitability but also higher or not. The use of debt or issuance of new equity may result in dilution of shareholders’ control and EPS. The company would have to weighthe cost and benefit of its options and strike an optimum balance to increase shareholder value.

3. Capital Structure

A company’s targeted capital structure is the debt equity ratio that the company wants to maintain over time. In determining its capital structure, a company must consider the implication of using debt. in general, increased use of debt will result in an increase in the risk borne by shareholders, which in turn leads to an increase in the expected rate of return required by the shareholders. As such, the company must balance this risk and return effect of using debt in order to determine the optimal capital structure for the company, that is one that maximises shareholder value.

Several factors influence the company’s capital structure decision. Among them are:

(a) Business risk – this is the risk inherent in the operations of the company. Generally, companies with higher business risk should have lower debt to equity ratios.

(b) Taxes – interest paid to debt holders is generally tax-deductible. This implies that a company with a high effective tax rate would be motivated to have a higher debt-to equity ratio.

(c) Financial flexibility – this refers to the company’s ability to raise capital under any condition.

(d) Management’s attitude towards risk – a conservative management would hesitate to use too much debt while an aggressive management will maximise the use of debt to increase the rate of return.

3.1 The effects of leverage

As mentioned above, the optimal structure is one where shareholder value is maximised. In this section, we shall take a brief look at operating and financial leverage and their effects on EPS. Our discussions will show that an increase in financial leverage will result in an increase in expected rates of return and at the same time, an increase in volatility risk. In the next section, we shall demonstrate how a company can determine its optimal capital expenditure.

Operating leverage

Operating leverage is a cost-accounting formula that measures the degree to which a firm or project can increase operating income by increasing revenue. A business that generates sales with a high gross margin and low variable costs has high operating leverage.

Operating leverage is the relationship between fixed cost and variable cost of a company. the higher the percentage of fixed cost to the total cost of a company, the higher the operating leverage. All things held constant, for a company with high operating leverage, relatively small changes to sales will result in a large change in operating income.

The degree of operating leverage (DOL) is the percentage change in earning in writing before interest and tax (EBIT) that results from a given percentage change in sales.

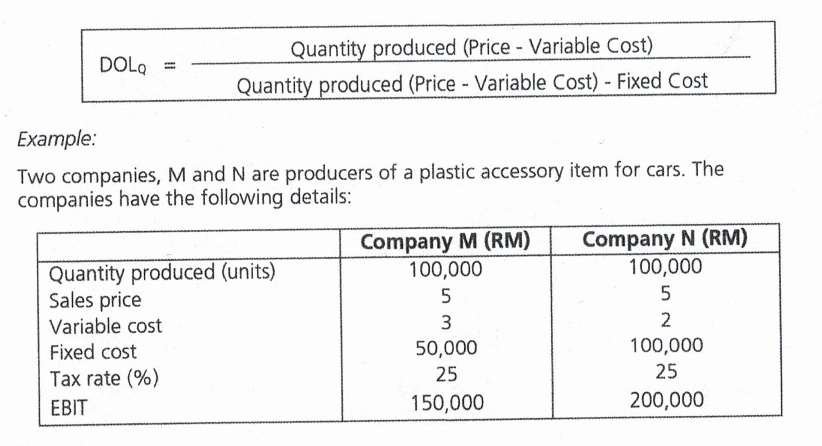

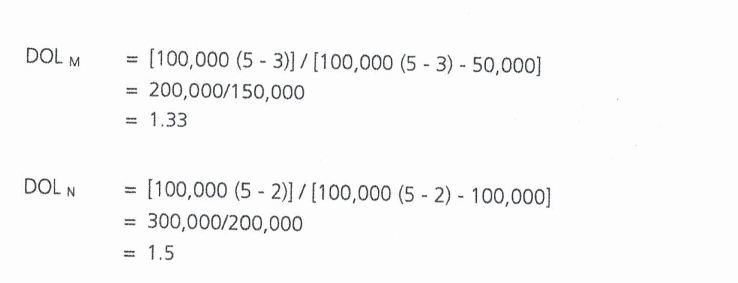

DOL = %ΔEBIT / %ΔSales

Another way to estimate DOL is:

The above suggests that if Company M increase its sales by 10%, EBIT will increase by 10% X 1.33 times. If Company N increases its sales by 10%, EBIT will increase by 10% X 1.5 times. As Company N has a higher fixed cost that Company M, DOLN > DOLM. Put another way, Company N’s EBIT is more sensitive to changes in the company’s sales than Company M.

Financial leverage

Financial Leverage refers to the use of debt (borrowed funds) to amplify returns from an investment or project. Investors use leverage to multiply their buying power in the market. Companies use leverage to finance to invest in their future to increase shareholder value rather than issue stock to raise capital.

Financial leverage refers to the use of interest bearing debt and measures the variability of earnings due to interest payments. As financial leverage increases, financial risk will increase (i.e. the additional risk that will be borne by shareholders due to financial leverage). This is shown by the increased sensitivity of the gross EPS to changes in the EBIT as a result of the interest payments.

The degree of financial leverage (DFL) shows the effect of changes on gross EPS due to the change in EBIT. The DFL is the percentage change in gross EPS for a given percentage change in EBIT.

If EBIT increases bt 10%, the EPS of the company will increase by 10% X 1.15 = 11.5%

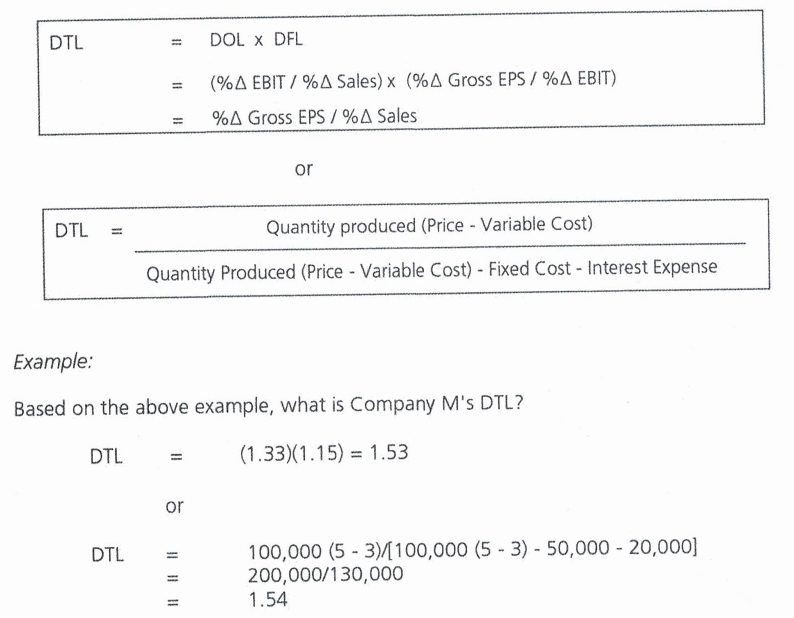

Degree of Total Leverage

The degree of total leverage (DTL) combines the effects of financial leverage and operating leverage. the degree of operating leverage shows that the greater the fixed operating coost, the more sensitive EBIT will be to sales while the degree of financial leverage shows that the greater the use of leverage, the more sensitive EPS will be to a change in EBIT. therefore, for a company that uses a high degree of operating leverage and financial leverage, EPS will be very sensitive to changes in sales.

Therefore, if Company M’s sales increase by 10%, Company M’s gross EPS is expected to increase by 10% X 1.54 = 15.4%.

Determining the optimal capital structure

The capital structure of a company refers to the proportion of debt and equity it uses to finance its business (i.e. finance its operations, capital expenditures, acquisitions, etc.). Having stated this, the optimal capital structure refers to the best or right mix of debt and equity that minimizes a company’s cost of capital, more specifically, the weighted average cost of capital (WACC), while maximizing its market value (i.e. shareholder wealth). The lower the cost of capital, the higher will be the company’s market value.

The optimal capital structure of a company is impacted by WACC, cost of debt, and cost of equity. Cost of capital is one of the major considerations that companies must take into account while deciding on their optimal capital structure. For any worthwhile investment, the expected return on capital must be higher than the cost of capital.

The above analysis shows that an increase in leverage will result in an increase in the sensitivity of EPS to changes in EBIT. theoretically, an increase in leverage will result in an increase in the returns of the company. However, an increase in leverage will also result in an increase in risks (volatility). In order to determine the optimal level of debt, a company would have to consider if the higher expected returns associated with the increased debt is enough to compensate shareholders for the increased risks.

We shall demonstrate this in the following example.

Example,

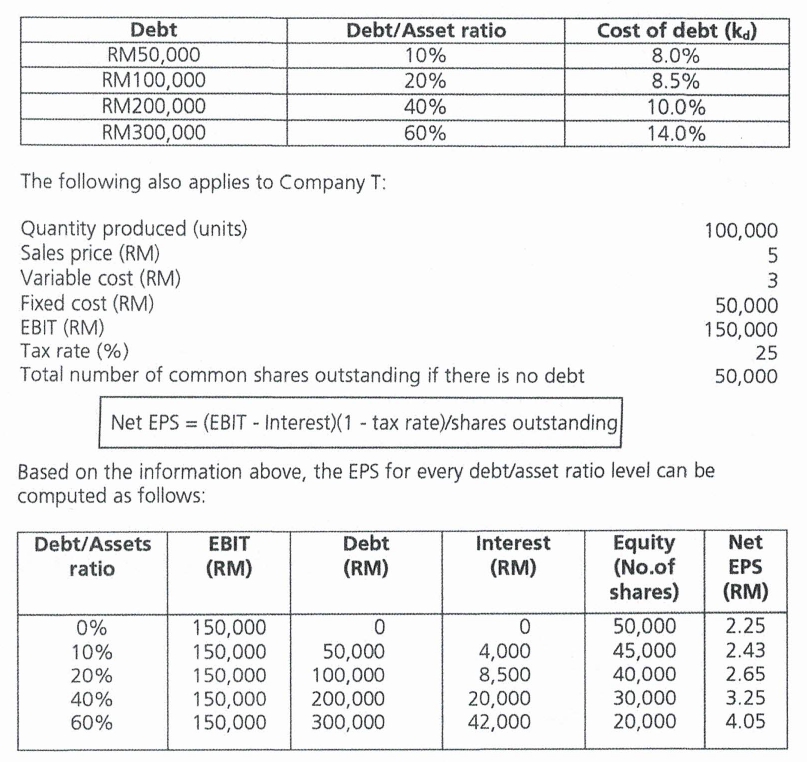

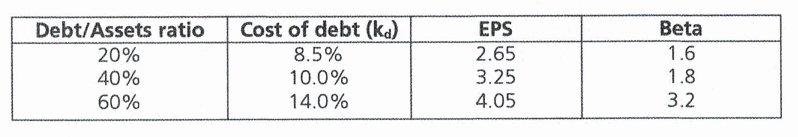

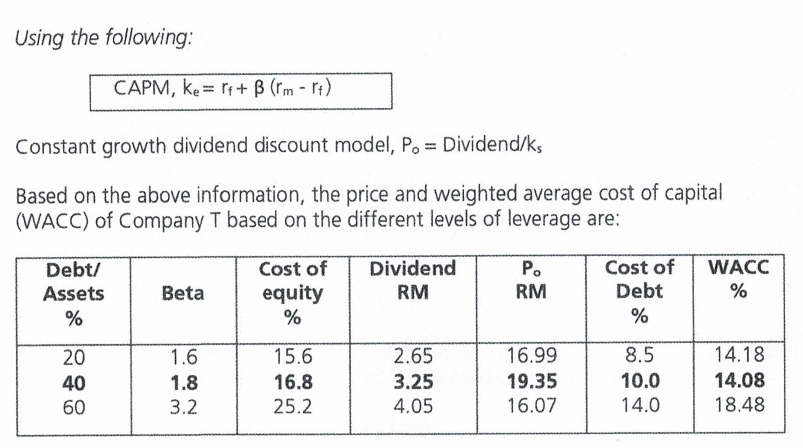

Let’s look at Company T. Suppose Company T has total assets of RM500,000. The table below sets out the cost of debt for each level of debt for Company T. Rationally, the cost of debt will increase as total amount of debt increases because debtholders recognise that, all things held constant, an increase in debt will result in an increase in risks so they will require higher rates of return.

Based on the above example, the optimal capital structure for Company T is a debt/asset ratio of 40% where the cost of capital is optimal. As the company increases its debt/asset ratio from 20% to 40%, its WACC declines. However, as debt increases further, both the cost of equity and cost of debt will also increase, resulting in an overall increase in WACC.

Financial Decisions in a Perfect Market

The concept of a perfect or efficient market has been discussed in Topic 7 of this Module. Briefly, an efficient market is where assets can be transferred with little loss in wealth, resulting in a “fair” pricing of assets in the market. A perfect market can be characterised by low or no barriers to entry, perfect competition, no transaction costs, information that is fully and readily available, no taxes and no restrictions on trading.

Before we carry on, let us briefly look at the concept of arbitrage. Arbitrage refers to buying an asset in one marketplace for the purpose of immediately reselling it at a higher price in another market. In other words, opportunities for arbitrage happen when an asset is sold at different prices in different markets. Riskless arbitrage occurs when the assets are acquired and sold for a riskless profit simultaneously. Competition among arbitrageurs contributes to market efficiency as this group is constantly looking for mispricing in securities with the aim of making a gain from the mispricing.

The actions of arbitrageurs will correct a mispricing.

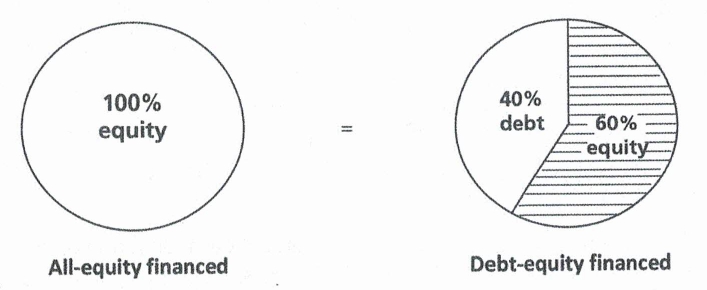

The funding mix of a company is called the capital structure of the company. When a company is fully financed by equity, the cash flows produced by its assets belong wholly to the shareholders of the company. On the other hand, when a company is financed by a mix of debt and equity, these cash flows are split into two streams — a fixed stream to debt holders and a residual stream to equity holders.

The value of a company can be expressed as the value of claims of its debtors and its shareholders. Thus, the value of a levered company equals the market value of its liabilities plus the total market value of equity [VL = EL + DJ. The value of an unlevered company is the value of its equity [Vu = Eu]. In the real world, the financing decision will have an effect on the value of the company.

The Modigliani-Miller Theorem

In 1958, Franco Modigliani and Merton Miller (M&M) published their work on Capital Structure Theory’. The initial Modigliani-Miller Theorem (MM Theorem) states that, in a perfect world, the capital structure decision will have no effect on the cash flows generated by the company and will also have no effect on the total value of the company. Thus, under their set of very restrictive assumptions, capital structure is irrelevant. It is important to understand the MM Theorem as it provides managers with a framework to focus on the important determinants of an optimal capital structure.

The MM Theorem holds only under certain restrictive assumptions:

(i) the sum of all future cash flows distributed to the company’s debt and equity investors are unaffected by the capital structure of the company;

(ii) there are no transaction costs;

(iii) there are no arbitrage opportunities exist;

(iv) there are no taxes;

(v) there are no bankruptcy costs;

(vi) investors can borrow at the same rate as corporations;

(vii) investors have the same information as management about the company’s future investment opportunities; and

(viii) EBIT is not affected by the use of debt.

In their original theorem, M&M recognised interest tax shields but did not value them properly. They subsequently presented an article in 1968, which recognised the effect of taxes.2

Based on the perfect market view of the capital structure, the value of the company or the “pie” is not affected by the way the company finances its investment. To simply illustrate:

Value here is determined by the size of the pie and not by how it is sliced.

M&M proved the theory that capital structure is irrelevant by demonstrating that arbitrage opportunities cannot exist in a perfect world and investors can undo the capital structure determined by the company.

Arbitrage opportunity

The MM Theorem is simple in its application. It basically states that, assuming we have two streams of cash flows, A and B, the present value of the sum of the two cash flows [PV(A+B)] is the same as the sum of the present value of cash flow A and cash flow B (PVA + PVB). Stated simply, the total value of a company’s debt and equity (total cash flows of the company) is fixed, no matter what the debt-equity mix is.

Example:

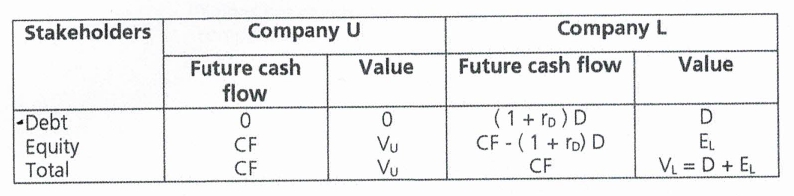

Assuming there are two companies, U and L that are identical in every way except for their capital structure. U has no debt while L has a debt obligation of RM(1+rD)D due in one year (assuming the debt is risk-free and rD is the risk free rate). Total cash flow for both these companies is CF.

Given the above, at the end of the year, the cash flows and market values of U and L are:

According to the MM Theorem, Vu must equal D + EL. If not, an arbitrage opportunity will exist. To illustrate this point, let’s assume that Vu > D + EL. Company U has an equity value of RM 100 million while Company L has debts of RM40 million and an equity value of RM50 million ERM100 million (Vu) > RM40 million (D) + RM50 million (EL)].

Theoretically, an investor could take advantage of this discrepancy by buying for instance 20% of the shares of Company L (RM10 million) and providing 20% of its debt (RM8 million) and short selling 20% of the shares of Company U (RM20 million).

In this example, the investor will earn a riskless RM2 million (in reality, investors may not be able to do this as short selling is not permitted in Malaysia). Based on the above example, under the MM Theorem conditions where no arbitrage opportunities can exist, the same investor should receive 20% x (CF – (1 + rD)D) and 20% x (1 + from Company L and has to pay out 20% (CF) for the short sale of shares in Company U. The total cash flows will add up to zero. Arbitrage opportunities will also exist if Vu <D + EL.

Given the assumption that arbitrage opportunities cannot exist, the total value of these two companies must be equal.

Undoing a capital structure

Another way of proving the MM Theorem is to demonstrate that investors are indifferent to the capital structure and changes to the capital structure of the company.

Example:

Company ABC is considering a change to its capital structure. The market value of the company’s equity is RM8 million (800,000 shares at RM10 each) while the value of the company’s debt is RM2 million. Let’s assume that the cost of debt is 6% per annum. Assume also that CF is the company’s cash flow to shareholders. Assume that any of the cash flows not used to service debt is paid to shareholders.

Investor Y owns 80,000 shares (10% of total equity). At the end of the year, investor Y’s share of the company’s cash flow can be computed as:

= 10% (CF – (1 + 0.06)2,000,000)

= 0.1 CF – 212,000

The company plans to change its capital structure by reducing its equity and increasing leverage. The company plans to do this by repurchasing 400,000 shares (50% of its equity) from its shareholders and funding the repurchase by issuing RM4,000,000 of debt at 6%. After the change in capital structure, assuming investor Y does not change his portfolio, investor Y will now own 20% of total equity in the company and the payoff will change to:

= 0.2 (CF – (1.06)6,000,000)

= 0.2 CF – 1,272,000

Investor Y could also adjust his portfolio to result in the same payoff as before the change in capital structure by selling 50% of his shares and using the proceeds to buy RM400,000 in bonds issued by the company (therefore bringing back his equity stake to 10%). His payoff after this adjustment is:

= 0.1 (CF – (1.06)6,000,000) + (1.06)(400,000)

= 0.1CF – 212,000

This example illustrates that based on the MM Theorem, without transaction costs and taxes, investors will be indifferent to the company’s capital structure because they can undo the effects of the change in the capital structure by changing their portfolios.

Taxes and capital structure

While the MM Theorem seems to show the irrelevance of capital structures, it is undeniable that financing decisions made by managers will have an effect on the value of the company. A decision perceived to be wrong could be detrimental to share prices and vice versa. In addition, the capital structure is still relevant because the assumptions of the initial MM Theorem are unrealistic. Recognising this, M&M subsequently presented a paper in 1968 in which the effects of debt on the cash flows and value of a company when taxes are present are recognised.

Effects of debt on the cash flows and value of a company

Let’s examine how corporate taxes will affect the cash flows and value of a company by looking at an illustration.

Illustration:

ABC is an all-equity company that has an equity value of RM40 million (4 million shares at RM10 each). Assume also that ABC’s corporate tax rate is 25% per annum. Other than the need to pay corporate taxes, we assume that ABC operates in a perfect market environment.

ash flows

For simplicity, we shall assume that ABC has a perpetual net cash inflow (before tax) of RM6 million per annum. Therefore, the expected after-tax income is (1- 0.25) x RM6 million = RM4.5 million, which will be fully paid out to shareholders. Assuming that ABC’s cost of equity is 15%, the value of equity in ABC will be RM4.5 million/0.15 = RM30 million.

Let’s assume ABC changes its capital structure by repurchasing 50% of its equity. The equity repurchased is financed by debt of RM20 million at the rate of 10% per annum. As such, there will be an interest payment of RM2 million (0.1 x RM20 million) per annum. However, because interest payments are tax deductible, the effective after-tax interest cost is only RM1.5 million [RM2 million x (1 – 0.25)]. The residual expected cash flow to be paid out to equity holders would then be RM3 million (RM4.5 million – RM1.5 million).

Value

Under the leveraged structure, shareholders would receive an additional RM20 million from the share repurchase and at the same time obtain RM3 million per year to invest at the rate of 15%. (Note that increased leverage usually means increased risk for the equity holders. With an all-equity structure, equity holders will bear all the risk of the company spread out over an investment value of RM30 million. With a debt-equity structure, equity holders will still have to bear all the company’s risk, but the risk is spread out over a smaller investment value of RM20 million (RM3 million/0.15). As such, investors would usually demand a higher required rate of return. However, for purposes of this example, we have used the same required rate of return of 15%.)

With annual cash flows of RM3 million invested at a required rate of return of 15% and the RM20 million cash from the share repurchase, total shareholder value will be:

Shareholder value,

= RM3 million/0.15 + RM20 million

= RM20 million + RM20 million

= RM40 million

Based on this example, use of leverage by the company had resulted in an increase in shareholder value by RM10 million (RM40 million – RM30 million).

At the same time, the total value of ABC, which was originally RM30 million, will increase by the same amount and the value of the company will be:

ABCaue,

= Value of debt + Value of equity

= RM20 million + RM20 million

= RM40 million

The above demonstrates that the use of leverage will result in an increase in shareholder and company value. What about the implications for corporate taxes?

Based on an all-equity structure, ABC would have paid corporate taxes amounting to RM1 .5 million per year (RM6 million x 0.25). With a 50% gearing ratio, ABC will pay only RM1 million taxes per year ((RM6 million – RM2 million) x 0.25). This is because the company would be able to enjoy tax deductions on interest.

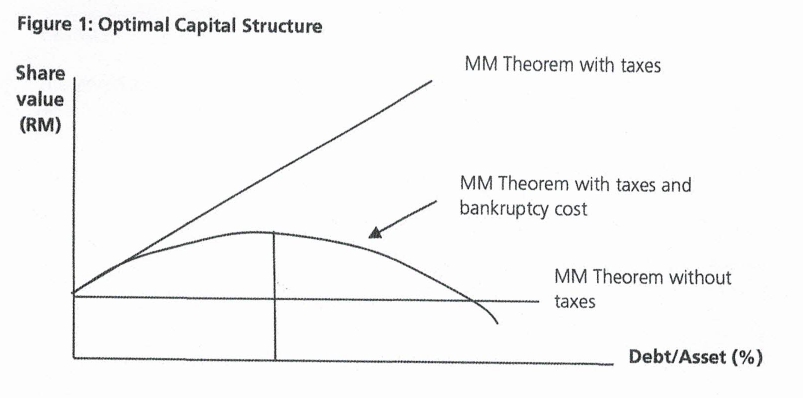

Based on the above, in a world with taxes, companies would be encouraged to use more debt in their capital structures in order to maximise values. In fact, based on the MM Theorem, in a perfect world with only taxes, the optimal capital structure should be 100% debt. We shall demonstrate later that this may not be entirely true.

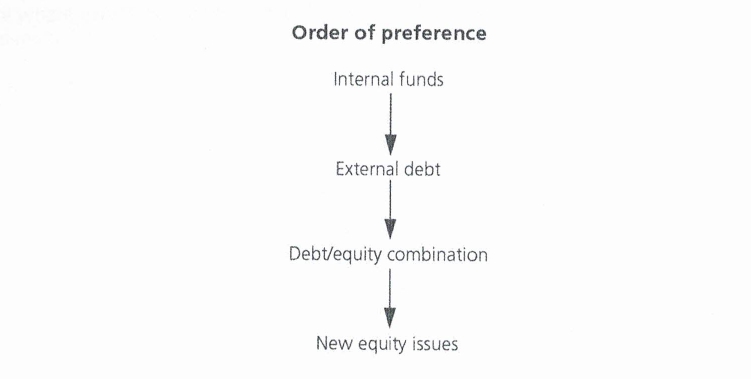

Transaction costs

Transaction costs play an important role in the financing decisions. Transaction costs result in the pecking order view of capital structure, which can be illustrated as follows:

An optimal capital structure is the best mix of debt and equity financing that maximizes a company’s market value while minimizing its cost of capital. Minimizing the weighted average cost of capital (WACC) is one way to optimize for the lowest cost mix of financing.

In practice, the transaction costs per RM1 of new equity raised will decline with increases in the size of the issue. This implies that companies should raise issues less frequently with a larger amount raised each time in order to minimise transaction costs. This also implies that as a result of transaction cost, the management of the company’s capital structure is important in ensuring that leakages of resources through issuance expenses is avoided or minimised.

In general, the total cost of obtaining new debt is typically lower than other forms of external financing. As such, in general, debt is generally more attractive relative to other methods of external financing.

Bankruptcy costs

In the previous section, it was stated that in a perfect world with only taxes, the optimal capital structure is 100% debt. We shall now introduce bankruptcy costs into the analysis. The MM Theorem discussed in the previous sections assumes no bankruptcy costs. Bankruptcy costs relate to costs that affect the cash flows of the company as a result of bankruptcy or the threat of bankruptcy.

There are two types of bankruptcy costs, direct and indirect. Direct bankruptcy costs relate to the legal process involved in a bankruptcy. Indirect bankruptcy costs arise in financially distressed companies which may find it difficult to obtain credit due to its financial situation (e.g. lenders may demand a higher rate of return for the increased risk of financial distress).

Let’s look at a company operating in an MM world with bankruptcy costs and taxes. As the company initially introduces small amounts of debt into its capital structure, the WACC of the company will fall (due to the tax deductibility of debt coupled with the lower cost of debt compared to cost of equity). However, as the company continues to increase its debt past a certain level, lenders and shareholders will increase their required rates of return (due to the increased risk of financial distress).

The rates of return will rise slowly at first and then rapidly as the percentage of debt to total assets ratio increases. At some point in time, WACC will bottom out and start to rise. Therefore, in a world with taxes and bankruptcy costs, there is an optimal capital structure where WACC is minimised and the share price is maximised. This can be graphically depicted as follows:

The Stakeholder theory

The stakeholder theory of capital structure basically suggests that the interaction of a company and its non-financial stakeholders is an important determinant of the company’s capital structure. Stakeholders of a company include not only the providers of capital but also the company’s suppliers, customers, employees and the community in which it operates. At the very extreme, where a manager makes a financial decision that puts the company at risk of financial distress, the stakeholders of the company will be affected. Customers may receive inferior products, suppliers may lose business, employees may lose their jobs the community may be disrupted. Companies under financial distress may find it more difficult for obtain continued support from their stakeholders.

Let’s examine how leverage affects the stakeholders of the company.

Liquidation

The liquidation of a company may have different effects on the debt and equity holders. As equity holders are the last ones to get paid in the event of liquidation, they would usually have strong motivations to avoid liquidation, even when it is financially rational to liquidate (i.e. the company’s liquidation value is more than its going concern value). On the other hand, lenders, who will get priority payment in the event of liquidation, may prefer liquidation to keeping a bankrupt company going (resulting in the deterioration of asset values).

Stakeholders will usually prefer not to do business with companies that are financially distressed or that may become financially distressed in the future in order to avoid any potential cost to them from liquidation. As increases in leverage will result in an increase in the probability of bankruptcy, the following example demonstrates that in deciding to take on more leverage, a company would have to consider whether the benefits from increased leverage (i.e. tax savings and increased rate of return) justify the cost of increased leverage resulting from stakeholders perception of an increased risk of financial distress (e.g. higher returns required by shareholders, shorter credit terms).

Example:

The engineers at a car manufacturer have recently completed a prototype design for a new model. The production department estimates a production cost of RM20,000 per unit. After conducting an initial marketing survey, the manufacturer estimates that it will be able to sell the car for RM40,000 per unit. This will result in gross profits of RM20,000 per unit, which will be subjected to 25% tax.

Management is considering using borrowings to fund 50% of the production cost of this new model, which will result in tax savings for the company. However, this will also result in an increase in the risk of financial distress to the company from say 10% to 20%. Although this is clearly a financing decision, management decided to conduct a market survey on the market perception of this decision. The results of the survey show that, customers are less prone to buy from the manufacturer if they perceive that there is a possibility of bankruptcy for whatever reason (i.e., fear of loss of technical and mechanical support and lack of automobile parts). The indicative price of RM40,000 is only applicable if the possibility of financial distress is at its original 10%.

Let’s assume that management estimates that the car is only worth RM18,000 if the company goes bankrupt. Based on a 20% probability of bankruptcy, customers would only be willing to pay RM35,600 per unit (0.8 (RM40,000) + 0.2 (RM18,000)).

Assuming the manufacturer estimates that it can sell 1,000 units per month, let’s see if it is worthwhile taking on extra leverage.

Assume that the company expects to sell 1,000 cars per month. Assume also that 50% of the production costs (or RM10,000) is financed by debt and the cost of debt is 8%. As such, interest cost is RM9.6 million (RM10,000 x 1,000 units x 12 months x 8%).

Without leverage, the company will make gross profits of RM240 million (RM20,000 x 1,000 x 12) per year and net profits of RM180 million.

The added leverage will result in tax savings of RM2.4 million per year (RM9.6 million x 0.25). However, the company’s gross profits will be reduced to RM187.2 million [(RM35,600 – 20,000) x 1,000 units x 12 months] and net profits reduced to RM 133.2 million KRM187.2 million -9.6 million)(1 -0.25)].

Based on the above, the company and its shareholders are better off without the additional leverage.

Financial distress

Not all companies that are in financial distress face the threat of liquidation. Increasing leverage may result in the company making a decision which may jeopardise the long-term interest of the company and its stakeholders. For example, under normal circumstances, companies are desirous of maintaining a good reputation to ensure their long-run profitability. However, companies under financial distress may discard long-run objectives and focus on the short-term need to generate cash and earnings to avoid bankruptcy. Companies may lower the quality of their products, cut corners or lengthen the period of the payables in order to generate sufficient cash to meet their debt obligations.

Conclusion

The purpose of this discussion on the Stakeholder Theory is basically to show that financial decisions made by a company have to take into consideration the effects on the stakeholders of the company. The financial condition of a company will have an effect on its decision as to whether to continue as a going concern and the quality of its products. A company’s financial condition will also affect how it is perceived by its stakeholders. The stakeholders view is especially important for companies that sell products or services that require a continuous relationship with the customers and products where quality is important but unobservable. For these kinds of companies, it is implied that they should have relatively less debt in their capital structures. Based on the stakeholder view, one of the reasons why some companies do not borrow, even when financing terms are attractive, is the perceived increase in the threat of bankruptcy or reduction in profits.

Financing decision involves the capital structure of the company. the finance manager has to determine what the optimal capital structure for the company is, i.e. one that maximises shareholder value. In so doing, the finance manager has to be aware of the risk and return trade-offs associated with the use of debt and to achieve an optimal balance structure between debt and equity for the financing of its investments.

The MM Theorem basically states that the capital structure decision is irrelevant in a perfect world. In this topic, we have shown that, after including taxes and bankruptcy costs, capital structure decisions are important in ensuring that shareholder value is maximised. The Stakeholder theory of Capital Structures which basically states that the capital structure decision made by the company will have an effect on its stakeholders. As such, the impact on shareholders is a determinant of capital structure.

Questions

1. Which of the following is a key determinant of operating leverage?

a. The company’s beta

B. Level and cost of debt

C. The competitive nature of the business

D. The trade-off between fixed and variable costs.

2. The company’s target capital structure should tend towards which one of the following?

A. Maximising risk

B. Minimising cost of equity

C. Maximising earning per share

D. Minimising weighted average cost of capital

Use the following information for questions 3 to 6.

Company Stud sells 10,000 units of its products at RM5 per unit. the company’s costs are RM8,000, interest expenses are RM2,000 and variable costs per unit is RM3,00.

3. What is Company Stud’s operating profits?

A. RM11,000

B. RM11,500

C. RM12,000

D. RM13,500

4. What is Company Stud’s degree of operating leverage?

A. 1.25

B. 1.50

C. 1.67

D. 1.75

5. What is Company Stud’s degree of financial leverage?

A. 1.00

B. 1.20

C. 1.33

D. 1.67

6. What is Company Stud’s degree of total leverage?

A. 1.25

B. 1.50

C. 1.75

D. 2.00

7. All of the following statements regarding the MM Theorem are TRUE, EXCEPT.

A. Under the MM Theoram with taxes, the company’s optimal capital structure is 100% debt.

B. Under the MM Theoram with taxes and bankruptcy cost, the value of the company will be maximised when WACC is maintained.

C. Under the MM Theoram with no taxes, the value of the company is dependent on the company’s capital structure.

D. Under the MM Theoram with taxes and bankruptcy costs, at a certain point, the WACC will increase with an increase in leverage.

.