Contents

Preview

About this topic

Topic objectives

The Costs of Compliance

The costs of compliance

The costs of non-compliance

The Benefits of Compliance

1987 Equity Market Cash

Facts

Key Issues

1991 Junk Bond Debacle

Facts

Key Issues

1997 Long-Term Capital management

Facts

Key Issues

Sumitomo

Facts

Key Issues

1997-198 Asian Financial and Economic Crisis

IOSCO Reports

Key Issues

The Financial Crisis of 2007-2009

Facts

Key Issues

Appendices

Checklist

Preview

About this topic

Compliance is a costly business, involving additional staff in the compliance team and audit committees and additional responsibilities for managers and supervisors as well as every staff member. To be effective, a compliance programme requires the staff to be trained and kept updated on a timely and continuous basis in addition to their daily responsibilities. Combined with fees which need to be paid to regulatory bodies, allocation of capital to adequacy requirements and additional paperwork, the

compliance programme needs to be included in a firm’s budget as one of the costs of business.

However, at every level of compliance, these costs need to be balanced against the risk. Obviously, greater resources need to be allocated to an area of greater risk. As we have seen, one of the Compliance Officer’s roles is to balance the need to comply (on a risk assessment basis) against the cost to the firm.

The costs of compliance also need to be viewed in the context of the benefits to the firm. It is very difficult to quantify the amount saved by avoiding fines or litigation or even the threat of litigation, or even the benefits, particularly in terms of enhanced reputation and the ability to attract well-qualified staff which flows from an effective compliance programme.

In this topic, we look at both the costs and benefits of compliance.

We will describe some major compliance failures, to highlight the compliance function and the consequences of failure.

Parings, the Junk Bond Debacle of 1991, Long-Term Capital Management and the 2007-2009 financial crisis are events which have become reminders to everyone in the financial markets of where things can go wrong, the magnitude of the consequences and provide lessons to help us identify what went wrong and how to avoid similar incidents from recurring.

In general, a common weakness was the assumption that the market and the

counterparties being dealt with were operating within limits that were manageable. The (weeding of those limits resulted in “disaster”.

Topic Objectives

At the end of this topic, you should be able to:

(a) explain the costs of compliance

(b) list the benefits of compliance

(c) explain the compliance failures and what went wrong

The Costs of Compliance

The costs of compliance

There are many different costs which relate to compliance. Firstly, there is a need for every firm to appoint a Compliance Officer who meets the relevant requirements. From previous topics, it is obvious that it may not be possible for one individual to undertake all of the functions of a Compliance Officer and he/she may need the support of a Compliance unit. These staff members would be an additional cost to the firm.

Monitoring and review need to be continuous and timely and are costly in terms of the extra time and resources required to undertake them. The frequency of reviewing and monitoring can be determined by assessing the level of risk involved and the nature and frequency of regulatory changes.

Training and education require an additional allocation of resources, and the time involved can be viewed as a cost to the firm. Similarly, regular meetings between the Compliance Officer and the supervisors are time-consuming and added responsibilities.

The financial requirements imposed on firms by the exchanges and/or clearing houses require capital adequacy in order for firms to operate in those markets. This limit on the use of capital is another cost.

The need for documentary evidence of compliance increases the amount of

administration and paperwork which has to be undertaken and completed by staff.

Another cost is, of course, the regulatory fees which have to be paid to the regulators and the generation of the required reports which must be lodged with the exchanges.

Research by the London Business School City Research Project in 1997 indicated that the cost of compliance in the securities and investment management sectors alone amounted to between £162 million and £221 million in 1996.

The costs of non-compliance

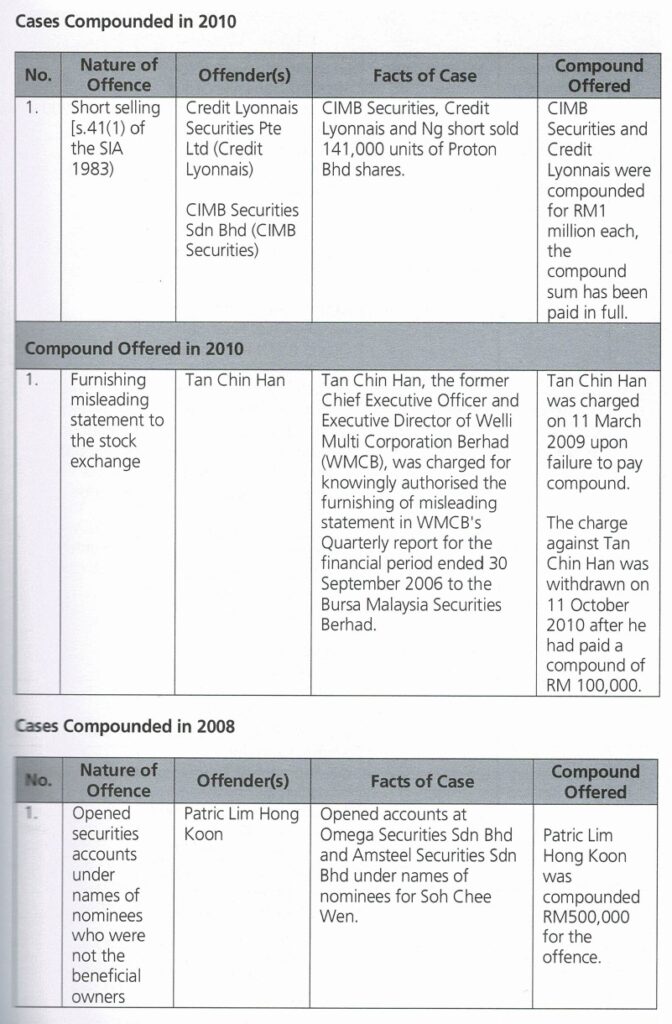

These Malaysian cases illustrate the costs of non-compliance to the firms involved.

The Benefits of Compliance

A compliance programme reduces the risk of potential and severe consequences of failure to comply with the law, rules of the exchange or appropriate business conduct.

There are many benefits of compliance, including:

(a). Better management of risk (due to effective compliance and prudential requirements), particularly operational risk, can enhance risk-adjusted returns and provide greater certainty in managing cash flow.

(b). Reduction in the incidence of disciplinary actions imposed on a firm such as fines or suspension from trading which may disrupt business as well as damage the firm’s reputation.

(c). Removal of the fear of litigation and the fear of imposition of penalties (some of which are personal) for failure to comply.

(d). A reduction in customer complaints and the costs of restitution and the time taken to “put things right”.

(e) Protection of business assets by decreasing the occurrence of unintentional errors or unethical or unfair practices (such as fraud) through quick detection and rectification and thus, a reduction in operating costs and financial risk.

(f) An enhancement of the company's reputation (particularly in comparison with the consequences of failure) and the reputation of its staff. This has a flow-on effect in terms of employee morale and the ease of attracting competent employees.

(g) Public confidence in the integrity of a firm can foster relationships with business partners.

(h) A basis for updating employee knowledge on legal and other changes in a regular and formal manner.

(i) The adoption of high standards assists the minimisation of credit, systemic and operational risk, which promotes long-term development in the industry. The Compliance Guidelines for Futures Brokers conclude that: Obviously, compliance will result in a lower incidence of disciplinary actions imposed on an organisation, e.g. fines and suspension from trading which may disrupt the business as well as damage the broker's reputation. More importantly, compliance by way of establishing control principles like segregation of duties and independent review serves to protect business assets by decreasing the occurrence of unintentional errors or outright fraud through quick detection and rectification. The effective penetration of a proper compliance culture into all business and administrative units of an organisation will bring about lower operational risk, facilitate earlier detection of market risk or concentration risk resulting in a higher level of operational efficiency, which in turn will translate into a reduction of operating costs and financial risk.

3 1987 Equity Market Crash 3.1 Facts The stock market prospered from 1982 to 1987 with many issuances of new securities followed by a surge in underwriting, trading and sales. The bond market expanded rapidly, large corporate profits resulted in new capital investments and new funds were raised for expansion. New funds were raised on the market using bonds and common stock financing. Interest rates began to creep upward from 1985 (when they had bottomed out) and by 1987, there were growing fears that worldwide interest rates would rise. During the week of 12 October, the market began to slide and the reaction spread very quickly worldwide. The date 19 October 1987 has become known as "Black Monday" --- the day the Dow Jones Industrial Average recorded the largest drop in one day, 508 points, the Standard & Poor's 500 stock index fell by 58 points (30%) and the NASDAQ Composite index fell 50 points (15%). In a matter of hours, the problem became of international concern as the other major markets felt the effects. </code></pre></li>

Key issues

International investment, the global economy and market linkages —

One of the major factors put forward in evaluating the cause of the 1987 crash is money that can be quickly moved from one market to another, seeking high returns (known as “hot money” or “high-velocity money”). The speed with which such money was moved at the time of the market break, caused all the markets to fall together. William McDonough of the New York Federal Reserve noted later that “the speed at which international investors redirect their capital has greatly shortened the time frame in which global situations have to be identified and agreed upon”. So fast was the market decline that regulators were caught unaware. Not only were world markets linked, but even the different markets in any one jurisdiction. The Crash demonstrated the linkages between the differing financial markets and that significant effects in one market can spill over into others.

- Programme trading — The development of software to automatically buy or sell in different markets to allow arbitrage between stocks, options and financial futures executed orders according to a predetermined strategy. It was certainly one of the contributing factors to the market collapse.

- Capital adequacy — The stockmarket crash on Wall Street threatened the viability of the exchanges and the stockbroking firms. The firms had relatively small amounts of capital which made them vulnerable to withdrawals by lenders given the loss of large amounts on stockmarket investments.

- Systemic risk — By 20 October, specialists had much larger inventories than usual as there were virtually no buyers, investors had margin calls to meet as prices fell and many were extended credit by stockbroking firms. The clearing houses, although well capitalised, weren’t able to bear such a large default risk.

All of the market players needed additional credit to continue functioning, but banks were reluctant to lend as the drop in asset prices affected creditworthiness and this increased the default risk. What happened? The Federal Reserve Bank intervened to prevent the systemic risk, by acting as lender of last resort so that the risk was transferred from the market participants to the banks and ultimately to itself, allowing the intermediaries to act as usual in the markets. This can be contrasted with the 1929 stock market crash where no intervention took place, intermediaries failed and the banking system collapsed, which prolonged the Depression. The 1987 crash highlighted the links between the banks and the investment banking community. - Market confidence — By intervening, the Federal Reserve Bank gave

confidence to the markets and avoided the expectation of a market meltdown. By increasing liquidity, the Federal Reserve helped to prevent a recession. However, foreign investors remained scared and money flowed to bonds for about six months and domestic investors abandoned the market. - Internationalisation of markets — The NYSE collapse caused serious market corrections for the rest of the world; no major market was exempt. In some countries the share prices fell by even greater amounts than those listed on the New York Stock Exchange.

Key changes in US financial market after the 1987 Crash — The New York

Stock Exchange, in response to the Crash restricted some forms of programme trading and instituted “circuit-breaker” mechanisms to reduce market volatility and promote investor confidence. The “circuit-breaker” will halt trading on the exchange if the Dow Jones Average falls by a certain amount on any day,

depending on the time of day and the amount of the drop. The rationale is that this time would allow dealers and brokers to contact clients and get new instructions or additional margin in relation to any large price movements.

Detractors have argued that circuit breakers induce trading in anticipation of a trading halt which would increase risk. It has also been noted that circuit breakers are much more difficult to impose when trading activity can move to markets that do not participate in the trading halt, given the continuing growth in international activity. Another change introduced after the 1987 Crash was uniform margin requirements aiming to reduce volatility for stocks, index futures and stock options. Changes were also made to clearing systems including back-up facilities to allow payments to clearing members to be made, even if a clearing member has defaulted and sounder agreements put in place.

Since 1987, there has also been a greater focus on risk management by both

supervisors and market participants.

1991 Junk Bond Debacle

Facts

The 1980s on Wall Street are remembered as the decade of junk bond take-overs, insider trading scandals, general financial excess and enormous merger deals. A complete review of the facts would require a book, so a brief overview follows.

A junk bond is a once highly rated bond of investment grade. The issuing company behind was performing badly, and so the bond price fell. Would the company be able to come back? If it did, the bondholder who purchased it cheaply would be rewarded with a rise in price. They were referred to as “junk” bonds because the businesses which issued them were more likely to default, in which case the investor would lose everything.

Michael Milken of Drexel Burnham Lambert developed a new issues market for companies that were unable to access the corporate bond market due to low credit ratings. In the junk bond market, the yield offered to investors had to be higher than for high quality bonds to balance the additional risk. So, the new bonds were issued at a discount to face value resulting in a higher yield for investors. The underwriting fees on

such issues were double those for ordinary bonds due to the substantial risks involved.

The market for junk bonds was mainly institutional, including savings and loans, insurance companies and bond funds. This market grew rapidly and remained extremely popular in 1985; however, it suffered in the market collapse of 1987 and began a serious decline as the junk bonds behaved like stocks and were as risky, and if the company which had issued the bonds had a decline in earnings, they were often not strong enough financially and found themselves on the verge of default. By 1988 the

junk bonds were difficult to sell and new accounting regulations made the savings and loans mark the bonds to market prices. As the prices tumbled, a crisis emerged. In 1989 the junk bond market collapsed. As a result, in 1990 Drexel itself began to run short of capital having paid several government fines and a large inventory of unsold junk bonds on its books. In February 1990, it filed for bankruptcy.

During the good days of the junk bond market, Milken devised elaborate schemes to sell junk bonds which ensured that buyers were well compensated for buying the issues which originated from Drexel. One example was a high-yield fund, Finsbury Management, managed by David Solomon. The fund inflated the price of the junk bonds it bought, sold them to investors and returned cash to Drexel and Milken (a kickback). In return, Milken provided benefits to Solomon’s private trading account at Drexel. It was deals such as this that ultimately caused Milken’s downfall.

From 1984, Milken used junk bonds to raise huge amounts of capital to fund hostile take-overs, acquisitions and leverage buy-outs which shook corporate America. He has been credited with fuelling the merger mania of the 1980s. For example, in 1985 the Coastal Corporation acquired American Natural Resources Company for US$2.46 billion — US$1.6 billion from bank loans and US$600 million from Milken’s junk bonds.

After a long government investigation, Milken pleaded guilty to six felonies including racketeering charges and securities fraud, and spent two years in prison. The US Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) settled with Drexel Burnham Lambert Inc.

Key Issues

- Lack of supervision — The SEC insisted on major changes to Drexel’s

compliance procedures and structure on the basis that “the Beverly Hills office (Milken’s office and department) functioned as a virtually autonomous unit” and “it is apparent that there wasn’t effective control by New York of that office.” However, it is interesting to note that, despite the Securities Act which provides for action to be taken against securities firm officials for failing to reasonably supervise with a view to preventing violations, the Chief Executive of Drexel was not charged with any wrongdoing. It was shown that Milken’s operations were not subjected to meaningful scrutiny by Drexel management and that compliance and supervisory officers at Drexel never questioned the eighteen transactions said to have involved unlawful activity. The people to whom Milken in fact reported and those who oversaw his trading activities did not truly hold positions of power over him, particularly as the junk bond operation was highly profitable. When an internal Drexel investigation took place, Milken and other staff members refused to answer questions. This would usually cause a firm’s management to seriously question its supervisory role and it is often the case that if an employee refuses to supply information, a firm would reassign them, place them on leave or dismiss them. - Conflict of interest — Milken chose his own compliance official who

participated in the junk bond department profits, which was a clear conflict of interest. - Non-recognition of suspicious trading patterns — It has been said that the records of the compensatory trades which were done by Drexel with Boesky (who confessed to insider trading) in which Drexel bought back securities it sold to Boesky within the previous 10 days at a 20% price increase, clearly evidenced a pattern of suspicious trading. Yet none of these were apparently questioned by Drexel’s management.

- Lack of Segregation — Milken ran the Beverly Hills office and was a trader, salesman, deal structurer, credit analyst, merger tactician and securities venturer. He had appropriated all of these diverse functions and did not have organisational demarcations within his group. Thus he was a walking

- contradiction of the principles of segregation and Chinese walls. There were, therefore, no appropriate checks. For example, Milken invested for himself, the firm, his group and his customers in real estate investment trusts, many of which Drexel had restructured; and he invested in both the debt and equity of Drexel deals for his investment partnerships.

- more, the hedge fund was unregulated and could operate in any market without capital or onerous reporting requirements. LTCM became one of the biggest players on the futures exchanges of the world in both debt and equity products. However, in order to return 40%, capital leverage had to be applied. Despite returning US$2.7 billion to its investors in 1997, its positions in the market were not reduced relative to the reduction in capital and so leverage in fact increased. In addition, LTCM increased its risks by, for example, investing in emerging markets such as Russia, playing the credit spread between mortgage-backed securities or double-A corporate bonds and taking

- speculative positions in take-over stocks. In 1998, its capital was US$4.8 billion.

- In August 1998, a moratorium was declared on Russia’s rouble and domestic dollar debt, and spreads widened in the bond markets. Instead of convergence between LTCM’s liquid instruments and other instruments which required a liquidity or credit premium, there was divergence and LTCM had to liquidate assets to meet margin calls.

- A letter to investors stated that in the year to September 1998, the fund had lost 52% of its value (US$2.5 billion). Meriwether was unable to find new capital. In fact, LTCM’s leverage was about 30 times on its balance sheet assets, but more like 300 times when the off-balance sheet business (for which the value of collateral had dropped significantly) was taken into account.

- The deterioration of LTCM’s situation caused concern about its effect on the markets.

- That concern centred around the fear that a default by LTCM would trigger default clauses in other swap agreements and the over-the-counter derivatives market could suffer a mass close-out and even system failure, or at least a mass panic.

- In order to avoid this occurring, the US Federal Reserve called meetings with large banks to find a solution. It was decided to try to put together a consortium of creditors to recapitalise the portfolio. Eleven banks put up US$300 million each, Societe Generale US$125 million and Credit Agricole and Paribas US$100 million, injecting fresh equity of US$3.625 billion. This avoided any fire sale of assets and allowed LTCM to be managed as a going concern. This was of particular importance to the regulators as the markets were volatile and investors nervous and it was considered a matter of public policy to resolve the LTCM problems quickly and efficiently. In July 1999, LTCM paid the consortium members US$1 billion and repaid US$300 million to its original investors.

Key Issues

(a) Inadequate risk management — LTCM in its risk management did not

sufficiently take into account stress testing, gap and liquidity risk, but instead relied heavily on theoretical models of market risk. Therefore, they were unprepared when credit spreads widened in September 1998, in practically every market at the same time. LTCM did not consider the liquidity risk involved in the derivatives transactions and the instruments underlying them.

(b) LTCM as a counterparty — LTCM was a not a bank counterparty, and yet it was not charged an initial margin on its swap and other transactions. LTCM’s collateral was thought to be sufficient, but did not adequately take into account margin calls on its deteriorating positions. The counterparties which dealt with LTCM did not have an informed view of LTCM’s leverage or its relationship with other counterparties. The Basel Committee on Banking Supervision stated in its report that “….heavy reliance on collateralisation of direct market-to-market exposures… in turn made it possible for banks to compromise other critical elements of effective credit risk management,

including upfront due diligence, exposure measurement methodologies, the

limit setting process and ongoing monitoring of counterparty exposure,

especially concentrations and leverage”.

Lack of regulation — LTCM was virtually unregulated, and while the SEC and NYSE had ascertained that no individual broker had an exposure to LTCM which jeopardised its capital or financial stability, they had not concerned themselves with the aggregate exposure of the market to LTCM.

Possibility of systemic risk — As there was in fact no systemic disruption, this is a matter for pure speculation. However, some have put forward the view that had LTCM not been bailed out, the liquidation of its highly leveraged positions would have had significant effect on the markets and could have led to systemic failure. In this regard, note the book Capital Ideas and Market Realities by Bruce Jacobs, Blackwell, 1999.

The article in Appendix 1 “How Long-Term Lost its Capital” analyses in detail what went wrong with risk management at LTCM.

Sumitomo

Facts

Hamanaka, a lawyer, worked for Sumitomo. He was known to work long hours and often late, refused transfers and was highly regarded. Unusually, he had authority to create brokerage and bank accounts, authorise cash payments (not usually a power given to a trader) and execute loan documents alone. These usually require more than one signature. It can be assumed that he knew what he was doing and his overtime was for reasons other than promotion. Hamanaka was well known in the world copper market, and recognised as an off-market trader — selling below the market, buying above it and selling over-the-counter options cheaply and in large quantities. In fact, his market dominance earned him the nickname of Mr. 5%.

Why trade off-market? Usually, to move prices (called “painting the tape”). Why sell cheap options? Usually, the primary motivation is to create income to cover bad price trading.

Hamanaka granted brokers power of attorney over Sumitomo trading accounts. This, in effect, lent Sumitomo’s debt capacity to third parties. His trading pattern increased in complexity and became larger and more transparent, and after 1993, this was accelerated by the use of futures, options and swaps. The positions were financed through credit lines and prepayment swaps with major banks (swaps that could be off balance sheet helped him to create liquidity). The trading volume, however, was relatively small and undertaken through offshore brokers which were newly formed and small and for whom he was a large proportion of their business. The firms, with the powers of attorney, were doing highly leveraged transactions in the name of Sumitomo, when Sumitomo thought they were trading cash and futures with the firm.

By the time Mr Hamanaka confessed, Sumitomo already had a large exposure to copper prices and even after unwinding some of the positions, Sumitomo announced a loss of $1.8 billion which had occurred over a 10-year period.

Key Issues

(a) Involvement of senior management — It is possible that senior

management did not understand that they were financially backing trades,

particularly those that were highly leveraged or involved mathematical

formulas. Perhaps they signed documents without understanding them or the

size of the risks inherent in the trades.

(b) Reputation — the transactions undertaken by the brokerage firms with power of attorney were highly leveraged, and “abused” the name of Sumitomo. In addition, the extreme adverse publicity surrounding these events and any law suit or potential law suit is extremely damaging.

(d) Accounting records— How did Hamanaka hide cash payments? Perhaps the

cash reports were falsified. If so, where were the control procedures which would have exposed this via a lack of reconciliation?

(e) Limits and risk management — The positions in the market were likely to exceed company limits or capital allocations and needed to be reduced so that there was appropriate diversification. This highlights procedural weaknesses that did not detect the exceeding of these limits and insufficient supervision and risk management. With more and more leveraged transactions, systems need to be developed to measure and assess leverage accurately and leverage risk from feedback producing positions like options. In addition, debt is easier to access as it can be generated using derivatives, and there needs to be an understanding of how to define debt and use liquidity to manage it.

- Proprietary trading — a firm needs to be careful to look for and avoid

conflict of interest between trading in a market itself and trading on behalf of a

client. This is of greater concern in small, highly concentrated markets where

there is value in information.

1997-98 Asian Financial and Economic Crisis

IOSCO reports

The lOSCO report entitled Causes, Effects and Regulatory Implications of Financial and Economic Turbulence in Emerging Markets contains an examination of “the causes, effects and regulatory implications of the financial and economic turbulence arising from the East Asian crisis of 1997-98”. This report can be accessed at www.iosco.org.

In addition to dealing with the background to the crisis, the report looked at issues including:

the role and functions of capital market regulators and the objectives of capital market regulation;

- systemic stability and market integrity including prudential regulation and risk

management by market participants;

- corporate governance;

• international financial architecture; and • implications of the crisis on securities 7.2 Key Issues What follows is a brief summary of the major issues. For more information, it is suggested that you obtain the entire report. • Credit risk -- The crisis highlighted the fact that sudden, sharp and sustained interest rate increases which occurred during the speculative attacks on their respective currencies rendered many long-term borrowers insolvent, thus transforming interest rate risk into credit risk. • Regulation and supervision — Regulatory reforms were viewed to be partial and incomplete, giving rise to loopholes which were exploited by firms. It has also been suggested that the absence of a strong culture of enforcement and accountability, led to prudential limits being breached on a regular basis without penalties being imposed. • Disclosure and corporate governance — It has been argued that inadequate disclosure and weak corporate governance allowed significant problems to build up in the financial and corporate sectors of many of the worst-afflicted jurisdictions. International investors and external creditors — due to a lack of due diligence on their part and also to the lack of transparency arising from inadequate disclosure and weak corporate governance on the part of domestic financial institutions and corporations — did not accurately appraise the situation. As a result, apparently questionable commercial decisions were argued to be insulated from market discipline. At the corporate level, the World Bank noted that the ownership structure of public-listed companies in certain jurisdictions were typically owner-managed. It was argued that such ownership structures did not readily promote the appropriate incentives for strong corporate governance and despite recent improvements in disclosure and other requirements there were perceived to be inadequate protection for minority shareholders. Poor corporate governance was also evident in the lack of impartial audit committees and of independent directors in some of the East Asian corporations. The absence of such oversight resulted in a lapse of discipline in corporate behaviour. • Investor confidence — A decline in market confidence poses a threat to the preservation of the systemic integrity of capital markets. Even the perception of financial distress can threaten systemic stability. This can be seen at three different levels. The first, over-confidence in considering some corporations as "too big to fail" with consequent excessive risk-taking on their part and the extensive system of cross guarantees which contributed to the "erosion of investor confidence when the situation began to deteriorate". The second is that "even a reasonably sound economy can be subject to panic and devastating runs on its currencies due to self-fulfilling rumours". According to this view, "a combination of panic on the part of the international investing community, policy mistakes at the onset of the crisis by Asian governments and poorly-designed rescue programmes turned the withdrawal of capital into a </code></pre></li>

full-fledged financial panic and deepened the crisis by more than was either necessary or inevitable”. The third relates to the loss of investor confidence as a result of the distortion of the price-discovery process, precipitating “further and more serious misalignments in asset prices”. Thus it was argued by some that the very existence of the price floor might have intensified selling pressure, resulting in a “magnet effect”. Investor confidence can generate positive side effects in the form of systemic stability.

Trading restrictions — As prices plummeted, trading restrictions and circuit breakers on many exchanges worldwide were activated. The efforts of the authorities to smooth the market movements and inhibit panic when selling pressure was high had “come under close scrutiny in view of their impact on liquidity and pricing efficiency”.

Systemic disruption —The crisis increased pressure on the stability and

integrity of the financial markets. “The… crisis increased the possibility of a collapse or default of key financial institutions or market intermediaries as a result of their exposure, directly or indirectly through clients, to capital markets and the broader financial system. Asset-specific and cross-asset volatility spill-over had an adverse impact on financial institutions and companies with large (often unhedged) exposures to currency and equity price risks. Currency volatility also led to higher and more volatile interest rates as monetary authorities intervened to stabilise exchange rates. This in turn raised concerns

over the integrity of the overall financial system…. Sharp movements in prices caused stockbrokers to activate their credit facilities at a time when banks were most likely either to reduce or withdraw these facilities”. Tight liquidity and weak market intermediaries and financial institutions exacerbated these risks. Prudential standards — As prices fell, the value of collateral pledged for margin loans was eroded. There was a high frequency of forced sales and margin calls. It was reported that "market intermediaries had difficulty in maintaining minimum prudential requirements and in financing their daily operations and short-term obligations throughout the crisis. This would have made it difficult to conduct core businesses.. ..Often the financial problems experienced by market intermediaries and the corporate sector were aggravated by the large number of links between securities markets, the rest of the financial system and the wider economy. The collapse and subsequent mass-suspension of financial institutions increased the pressure on market intermediaries. For example, stockbrokers in one jurisdiction suffered a credit- squeeze after the suspension of domestic finance companies".

The Financial Crisis of 2007-2009

Facts

The bursting of the US housing bubble is one of the major factors which led to the 2007-2009 Financial Crisis. With the bursting of the housing bubble, the values of securities which were tied to the US real estate pricing plummeted causing damage to financial institutions around the world. The crisis had, among others, resulted in the collapse of big institutions such as Lehman Brothers, the bailout of institutions such as

Federal National Mortgage Association (Fannie Mae), Federal Loan Mortgage

Corporation (Freddie Mac) and American International Group (AIG), and acquisitions of institutions such as Bear Stearns and Washington Mutual by JPMorgan Chase.

Key issues

The US housing market — Following the dotcom bust, the Federal Reserve

had lowered the federal funds rate from 6.2% to 1.0% between the years

2000 to 2003. The low interest rates had encouraged borrowing and banks

had given out more loans to potential homeowners. As more loans are given

out, the housing price starts to appreciate. However, between the months of July 2004 to July 2006, the Federal Reserve had raised the federal funds rate.

The increased rates contributes to an increase in the adjustable-rate mortgage (ARM), making the ARM interest rate resets higher. As the rates increased, the housing price starts to drop and borrowers’ ability to refinance became more difficult. As a result, defaults and foreclosure increased. The problem that arose from the US housing market then spread to the financial markets because of the manner loans were re-packaged and distributed to the global financial markets.

Role of the financial industry — Complicated financial instruments such as mortgage-backed securities (MBS) and collateralised debt obligations (CDO) which generally derived their value from mortgage loans and housing prices were introduced. Such instruments enabled institutions and investors from around the world to invest in the U.S. housing market. As the U.S. housing prices dropped, financial institutions which had borrowed and invested heavily in the aforementioned financial instruments were also affected.

Risk pricing — The risk inherent to financial instruments such as MBS and

CDOs was not accurately measured. Market participants also failed to

understand the impact of such financial instruments to the overall stability of the financial system.

Lack of regulation — There was lack of regulation particularly in the

unregulated over-the-counter credit default swap (CDS). The lack of regulation allowed firms like AIG to make as many CDS as they wanted. As long as the insurer remained AAA-rated, they did not need to put up any collateral.

Checklist

Below is a checklist of the main points covered in this topic. Use this checklist to test your learning:

(a) To be effective, a compliance programme requires the staff to be trained and kept updated on a timely and continuous basis in addition to their daily responsibilities.

(b) There are many different costs which relate to compliance.

(c) There are many benefits of compliance, including:

(d) Better management of risk (due to effective compliance and prudential requirements), particularly operational risk, can enhance risk-adjusted returns and provide greater certainty in managing cash flow.

(e) Reduction in the incidence of disciplinary actions imposed on a firm such as fines or suspension from trading which may disrupt business as well as damage the firm’s reputation.

(f) Removal of the fear of litigation and the fear of imposition of penalties (some of which are personal) for failure to comply.

(g) A reduction in customer complaints and the costs of restitution and the time taken to “put things right”.

(h) Protection of business assets by decreasing the occurrence of

unintentional errors or unethical or unfair practices (such as fraud) through quick detection and rectification and thus, a reduction in operating costs and financial risk.

(i) An enhancement of the company’s reputation (particularly in

comparison with the consequences of failure) and the reputation of its

staff. This has a flow-on effect in terms of employee morale and the ease

of attracting competent employees.

(k) Public confidence in the integrity of a firm can foster relationships with business partners.

(l) A basis for updating employee knowledge on legal and other changes in a regular and formal manner.

(m) The adoption of high standards assists the minimisation of credit,

systemic and operational risk, which promotes long-term development in

the industry.