Outline/Topics

(1) Introduction

(2) Nature of Money in Shariah

(3) Riba and Its Prohibition

(a) Classification of riba

(b) Verses on absolute prohibition of Interest

(c) The Nature of Loan in Shariah

(d) Overall Effects of Interest

(4) GHARAR: Concept and Forms

(a) Gharar in modern contracts

(5) Qimar: Concept and Forms

(a) Conditions of Qimar

(b) Forms of Qimar

(6) Shariah Perspective on Time Value Of Money

(7) Calculation of time value of money

(a) Simple Interest

(b) Compound Interest

(c) Nominal Interest Rate

(d) Effective Interest Rate

(e) Present Values & Future Values

(f) Net Present Value (NPV)

(g) Internal Rate of Return (IRR)

(h) Amortization

(8) Conclusion

Study/Reading Objectives:

Upon completion of this chapter you should have basic knowledge of:

(a) Nature and Identity of Money in Shariah

(b) Ribā (Interest) and Its Prohibition

(c) Gharar (Uncertainty): Concept and Forms

(d) Qimār/Maysir (Gambling): Concept and Forms

(e) Time Value of Money from the Perspective of Shariah

(f) Calculation of Time Value of Money

Definitions:

Mu’amalat – Mu’amalat is an Arabic word, meaning Financial Transactions.

Shariah – Shariah is the practices or activities in conformity to the Islamic law.

(1) INTRODUCTION

Financial planning is about managing one’s finances and planning for future financial activities. This involves monetary transactions and various computations pertaining to money. A financial transaction – Fiqh al-Mu`amalat is the traditional Islamic discipline concerned with the jurisprudence of financial transactions. In Shariah financial planning, a financial planner should have a clear idea about the nature and function of money in accordance with Shariah. Shariah has imposed various controls in the form of prohibitions to ensure that money performs its expected function in the economy and is not abused in a manner that leads to exploitation and injustice. A major prohibition in Shariah with regard to financial dealings is ribā, followed by gharar (uncertainty in contracts) and qimār (gambling). This chapter aims at explaining briefly the essential concepts pertaining to these.

Financial planning is to set financial goals relating to the future. In order to meet such financial goals, investments have to be made at present, which results in sacrificing present money for monetary returns in the future. This is why the time value concept of money is important in financial planning. In setting financial goals, it is helpful to express the client’s goals quantitatively and numerically. Using time value concept, values related to retirement planning, education planning for children, assessing the adequacy of existing financial resources and assets to meet various goals, etc., could be measured in a clear manner. The outline of the time value concept as presented in modern commerce and finance, together with the basic computation models related to financial planning, namely, the single sum model and the annuity (regular cash flow) model are discussed in this chapter with examples. Finally, some clarification is provided on the Shariah perspective of the time value of money.

(2) NATURE OF MONEY IN SHARIAH

One of the presumptions on which all theories of interest are based is that money is treated as a commodity. It is, therefore, argued that just as a merchant can sell his commodity for a higher price than his cost, he can also sell his money for a higher price than its face value; or, just as he can lease his property and charge a rent against it, he can also lend his money and claim interest thereupon.

Islamic principles, however, do not subscribe to this presumption. Money and commodity have different characteristics and therefore, they are treated differently. The basic points of difference between money and commodity are as follows:

(a) Money has no intrinsic utility. It cannot be utilized in direct fulfillment of human needs. It can only be used for acquiring goods or services. A commodity, on the other hand, has intrinsic utility and can be utilized directly without exchanging it for some other thing.

(b) Commodities can be of different quality while money has no quality except as a measure of value or a medium of exchange. Therefore, all units of money of the same denomination, are hundred per cent equal to each other. This means an old and dirty note of RM100.00 has the same value as a brand new note of RM100.00.

(c) In commodities, the transactions of sale and purchase are effected on an identified particular commodity. If A has purchased a particular car by pin-pointing it, and the seller has agreed, he deserves to receive the same car. The seller cannot compel him to take delivery of another car, though of the same type or quality. Money, on the contrary, cannot be pin-pointed in a transaction of exchange. If A has purchased a commodity from B by showing him a particular note of RM100.00 he can still pay him another note of the same denomination.

Based on these basic differences, Islamic Shariah has treated money differently from commodities, especially on two scores:

(i). Money (of the same denomination) is not held to be the subject matter of trade or lease, like other commodities. Its use has been restricted to its basic purpose i.e., to act as a medium of exchange and a measure of value.

(ii). If for exceptional reasons, money has to be exchanged for money or it has to be borrowed, the payment on both sides must be equal and such that it is used for the defined purpose only. The trading of money is prohibited, unless when money is traded at par at the current exchange value, which is termed as AL-SART in Islamic finance. Any premium on the exchange of money amounts to RIBA.

(3) RIBĀ AND ITS PROHIBITION

The word RIBA means excess, increase or addition. This term, in Shariah terminology, implies “any excess compensation which is not matched by a counter value/consideration”.

A more comprehensive definition of ribā could be “an excess not matched by a return, according to Shariah criteria, that is stipulated for one of the contractors”.

The meaning of ribā has been clarified in the following verses of Qur’ān: “Those who devour interest will not stand except as stands one whom Evil One by his touch hath driven to madness. That is because they say: ‘Trade is like usury’, but Allah hath permitted trade and forbidden usury. Those who, after receiving direction from their Lord, desist, shall be pardoned for the past; their case is for Allah (to judge); but those who repeat (the offence) are Companions of the Fire: they will abide therein (for ever)” (al-Baqarah (2): 275)

“O ye who believe! Fear Allah, and give up what remains of your demand for usury, if ye are indeed believers. If ye do it not, take notice of war from Allah and His Messenger: but if ye turn back, ye shall have your capital sums: deal not unjustly, and ye shall not be dealt with unjustly” (al-Baqarah (2) :278-279).

The verses clearly indicate that the term ribā means any excess compensation over and above the principal which is without due consideration. However, the Qur’ān has not altogether forbidden all types of excess as it is present in trade, which is permissible. The excess that has been rendered prohibited (ḥarām) in Qur’ān is a special type termed ribā. Prior to Islam, the Arabs used to accept ribā as a type of sale, which unfortunately, is still being an accepted meaning at present times. Islam has categorically made a clear distinction between the excess in capital resulting from sale and excess resulting from interest. The first type of excess is permissible but the second type is forbidden and rendered ḥarām, as clearly laid down in the Qur’anic verse: “They say: ‘Buying and selling is but a kind of interest’, even though Allah has made buying and selling lawful, and interest unlawful” (al-Baqarah (2): 275). Classification of Ribā

There are two types of ribā, namely RIBA AL-NASI’AH and RIBA AL-FADL.

(a) Ribā al-Nasī’ah

Ribā al-Nasī’ah is defined as excess against deferment. This result from predetermined interest that a lender receives over and above the principal sum lent (ra’s al-māl). It is defined with regards to financial transactions as any contractual increment in a loan or debt due to the time element, for example, lending RM100.00 for repayment in a month, where the borrower is required to pay RM110.00.

This is the real and primary form of ribā. Since the verses of the Qur’ān have directly rendered this type of ribā as prohibited, it is also called ribā al Qur’ān. It is a loan where against a specified repayment period an amount in excess of capital is predetermined. The Holy Prophet (s.a.w.) said:

“Every loan that draws interest is Ribā”

Ribā al-Nasī’ah refers to the addition of the premium which is paid to the lender in return for his waiting as a condition for the loan and is technically the same as interest. The prohibition of Ribā al-Nasī’ah is one of those issues which have been confirmed in the revealed laws of all Prophets (peace be upon them). (See Exodus 22:25, Leviticus 25:35-36, Deuteronomy 23:20, Psalms 15:5, Proverbs 28:8, Nehemiah 5:7 and Ezekiel 18:8,13,17 & 22:12). Also, various verses of the Qur’ān stated its prohibition of ribā. It warns those who persist in practicing it of a war which is certain to be declared on them by Allah Himself and His messenger, especially on those engaged as writers, witnesses and dealers in ribā transactions.

According to the above definition of ribā al-nasī’ah, the giving and taking of any excess amount in exchange of a loan at an agreed rate is included in interest irrespective of the rate. The fact that ribā al-nasī’ah is categorically prohibited has never been disputed in the Muslim community.

Riba al-nasi`ah is one of the two categories into which riba is often divided by the fuqaha’, the other being riba al-fadl. Riba al-nasi’ah takes place when two ribawi substances (see al-amwal al-ribawiyyah) are exchanged, one immediately and the other with a delay.

An example of riba al-nasi’ah: Two parties agree to exchange 10 kilos of gold for 2 kilos of silver such that the former is handed over immediately and the latter is to be delivered 2 weeks from the date the contract is signed. Another example: Two traders exchange 1 metric ton of wheat for 2 metric tons of barley such that the latter is delivered after one year.

In short, the ribā of today which is supposed to be the pivot of human economy and features in discussions on the problem of interest is nothing but this ribā, the unlawfulness of which stands proven on the authority of the seven verses of the Qur’ān, more than forty ḥadīth or the Prophet’s sayings and of the consensus of the Muslim community.

The wisdom of the prohibition of ribā al-nasī’ah is that it prohibits the overall effect of loss resulting in a debtor having to pay an addition to the amount owed. In ribā al-nasī’ah, the consumer of ribā does have some casual and transitory profits apparent to him, but its curse in this world and in the Hereafter is much too severe compared to this benefit. The ribā consumer suffers such spiritual and moral loss that it virtually takes away the great quality of being ‘human’ from him. No sane and just person will say that personal and individual gain which causes loss to the whole community or group is useful. The evil effects of ribā on the economy are outlined below under “overall effects of interest”.

(b) Ribā al-Faḍl

The second classification of ribā is ribā al-faḍl. Since the prohibition of this ribā has been established on Sunnah, it is also called ribā al-ḥadīth. Ribā al-Faḍl is defined as excess compensation not matched by a countervalue/consideration in the sale of goods. This means an excess which is taken in the exchange of specific homogenous commodities in their hand-to-hand purchase and sale.

The Prophet (s.a.w.) said, “Sell gold in exchange of equivalent gold, sell silver in exchange of equivalent silver, sell dates in exchange of equivalent dates, sell wheat in exchange of equivalent wheat, sell salt in exchange of equivalent salt, sell barley in exchange of equivalent barley, but if a person transacts in excess, it will be usury (ribā). However, sell gold for silver anyway you please on the condition it is hand-to-hand (on the spot) and sell barley for dates anyway you please on the condition it is hand-to-hand (on the spot)”.

The six commodities, if they are exchanged among the same category/genus, can only be exchanged in equal quantities and on the spot. An unequal sale or a deferred sale of these commodities will constitute ribā. These six commodities in Islamic legal terminology are called AMWAL RIBAWIYYAH.

These commodities refer in general to what is used as mediums of exchange (such as, gold and silver) and eatables. Therefore, this law will apply to everything edible or having the natural ability of becoming a medium of exchange (currency). Any exchange of these items should be done in equal quantities only when the exchange involves homogenous items. For example, 1 ton of wheat may be exchanged only against 1 ton of wheat. Any excess on one side would form ribā.

Similarly, when eatables are exchanged with eatables of another genus, or currencies are exchanged with currencies of another denomination, the transaction must take place on the spot. For example, exchanging 100kg of rice against 90kg of wheat is permitted, provided it is done on the spot. Selling 10g of gold for RM1000.00 is permitted, provided the transaction is carried out on the spot.

Verses on Absolute Prohibition of Interest

Allah Says: “O ye who believe! Fear Allah, and give up what remains of your demand for usury, if ye are indeed believers. If ye do it not, take notice of war from Allah and His Messenger: but if ye turn back, ye shall have your capital sums: deal not unjustly, and ye shall not be dealt with unjustly” (al-Baqarah (2): 278-279).

The above two verses demand one to abandon the amount of ribā and direct that only the principal amount should be paid back with nothing in excess. The second verse explains that any excess on principal, no matter how insignificant, is cruel.

The following ḥadīth also proves that interest is forbidden: “Listen! All Ribā that were due in the pre-Islamic days have been completely eliminated. You have to pay back the principal amount only”.

Shariah prohibited the normal ribā, and also extend the prohibition to the compounding ribā. The compounding ribā occur normally when there is a delay or default. Hence both are prohibited in Shariah.

Allah Says: “O believers, take not doubled and redoubled interest, and fear God so that you may prosper. Fear the fire which has been prepared for those who reject faith, and obey God and the Prophet so that you may receive mercy” (Ól-ʿImrān (3): 130-132)

The Nature of Loan in Shariah

Another major difference between the secular capitalist system and the system based on Islamic principles is that under the former system, loans are purely commercial transactions meant to yield a fixed income to the lenders. Islam, on the other hand, recognize qarḍ hasan but does not recognize loans as income-generating instruments. They are meant only for those lenders who do not intend to earn a worldly return through them. They, instead, lend their money either on humanitarian grounds to achieve a reward in the Hereafter, or merely to save their money through a safer hand. So far as investment is concerned, there are several other modes of investment-like partnerships and others which may be used for that purpose. The transactions of loans are not meant for earning income.

The basic philosophy underlying this scheme is that the one who is offering his money to another person has to decide whether:

(a) He is lending money as a sympathetic act; or

(b) He is lending money to the borrower, so that his principal may be saved; or

(c) He is advancing his money to share the profits of the borrower.

In the former two cases (a) and (b) he is not entitled to claim any additional amount over and above the principal, because in case (a) he has offered financial assistance to the borrower on humanitarian grounds or any other sympathetic considerations; and in case (b) his sole purpose is to save his money and not to earn any extra income.

However, if his intention is to share the profits of the borrower, as in case (c), he shall have to share the latter’s losses too, should such losses occur. In this case, his objective cannot be served by a transaction of loan. He will have to undertake a joint venture with the borrower, whereby both of them will have a joint stake in the business and will share its outcome on a fair basis.

For case (c), the advancing of money for the purpose joint venture is Shariah compliant as this is similar to the mushārakah contract in Islam.

Overall Effects of Interest

Conversely, if the intent of sharing the profit of the borrower is designed on the basis of an interest-based loan, it would mean that the financier wants to ensure his own profit, while he leaves the profit of the borrower at the mercy of the actual outcome of the business. If the business fails, the borrower will not only bear the losses of the business, but will also have to pay interest to the lender. This means the profit or interest of the financier is guaranteed at the price of the loss to the borrower, which is obviously, a glaring injustice.

On the other hand, if the business of the borrower earns huge profits, the financier will have a sizeable share in the profits. However, in an interest-based system, the profit of the financier is restricted to a fixed rate of return which is governed by the forces of supply and demand of money and not on the actual profits produced on the ground. This rate of interest may be much less than the sizeable portion a financier might have deserved, had it been a joint venture. In this case the major part of the profit is secured by the borrower, while the financier gets much less than deserved by his input in the business, which is another form of injustice.

Thus, financing a business on the basis of interest creates an imbalance which has the potential of bringing injustice to either of the two parties in different situations. Hence, the Shariah does not approve of an interest-based loan as a form of financing.

Once interest is banned, the role of “loans” as practiced in the conventional banks for commercial activities becomes very limited, and the whole financing structure turns out to be equity-based or transactions backed by real assets such as in case of raising finance through ṣukūk. In order to limit the use of loans, the Shariah has permitted the borrowing of money only in cases of dire need, and has discouraged the practice of incurring debts for living beyond one’s means or to grow one’s wealth.

The Holy Prophet (s.a.w.) refused to offer the funeral prayer (ṣalāt al-janāzah) to a person who died indebted was, in fact, to establish the principle that incurring debts should not be taken as a natural or ordinary phenomenon of life. It should be the last thing to resort to in the course of economic activities.

Abū Saʿīd al-Khudrī reported that a dead body was brought to the Messenger of Allah for his funeral prayer. He enquired. “Is there any debt due from your companion? Yes”, said them. He asked again. “Has he left anything for payment? No”, they said. He then said; “Pray for your companion”. ʿAlī ibn Abī Ṭālib said, “O Messenger of Allah! His debt is upon me”. Then, he stepped forward and offered his funeral prayer.

In a narration of the same meaning he said, “May Allah save your surety from Hell as you saved the loan of your brother Muslim. There is no Muslim who pays off the debts of his brother but Allah will save his surety on the Resurrection Day”.

Conversely, once interest is allowed, and advancing loans becomes a form of profitable trade, the whole economy turns into a debt-oriented economy. It will then not only dominate the real economic activities and disturb its natural functions, but will also put the whole of mankind under the slavery of debt. It is no secret that many nations in the world, including the developed countries, are drowned in national and foreign debts to the extent that the amount of payable debts in a large number of countries exceeds their total income.

Interest-based loans have a persistent tendency in favor of the rich and against the interests of the common people. It carries adverse effects on production and allocation of resources, as well as on the distribution of wealth. Some of these effects are as follows:

(a) Evil Effect on Allocation of Resources

Loans in the present banking system are given mainly to those who, on the strength of their wealth, can offer satisfactory collateral. The banking system thus, tends to reinforce the unequal distribution of capital.

(b) Evil Effects on Production

Since in an interest-based system funds are provided on the basis of strong collateral and the end-uses of the funds do not constitute the main criterion for financing, it encourages people to live beyond their means. The rich do not just borrow for productive projects, but also for conspicuous consumption. Similarly, governments borrow money not only for genuine development programs, but also for their lavish expenditure and for projects motivated by their political ambitions rather than by sound economic assessment.

(c) Evil Effects on Distribution

In the present banking system, the injustice brought to the financier is more pronounced and much more disturbing to the equitable distribution of wealth. In the context of modern capitalist system, it is the banks which advance depositors’ money to the industrialists and traders. Almost all giant business ventures are financed by banks and financial institutions. In numerous cases the funds deployed by the big entrepreneurs from their own pockets are much less than the funds borrowed from the common people through banks and financial institutions.

The net result, in this case, is that all the profits of the big enterprises are earned by persons whose own financial input may be marginal, while the people whose financial contribution may have formed the largest part of the investment get nothing in real terms. This is because the amount of interest given to them is often repaid by them through the increased prices of the products, and therefore, in a number of cases the returns received becomes negative in real terms.

(4) GHARAR: CONCEPT AND FORMS

Gharar is another factor that plays a role in deciding the Shariah validity or otherwise of a transaction. The Arabic word gharar means risk, uncertainty, and deceit. While the prohibition of ribā is absolute, some degree of gharar or uncertainty is acceptable in the Islamic framework. Only conditions of excessive gharar need to be avoided.

Gharar is defined as any bargain where the outcome is hidden. Gharar sale is defined as the sale of probable items whose existence or characteristics are not certain, due to the risky nature which makes the trade similar to gambling.

The Qur’ān has clearly forbidden business transactions which cause injustice in any form to any of the parties. It may be in the form of hazard or peril leading to uncertainty in any business; or deceit, fraud or undue advantage.

Allah says: “And eat not up your property among yourselves in vanity, nor seek by it to gain the hearing of the judges that ye may knowingly devour a portion of the property of others wrongfully” (al-Baqarah (2): 188).

Allah says: “O ye who believe! Squander not your wealth among yourselves in vanity, except it be a trade by mutual consent, and kill not one another. Lo! Allah is ever Merciful unto you” (al-Nisā’ (4): 29).

There is no text in Qur’ān expressly concerning the ruling of gharar, whether of a general or particular nature. However the Qur’ān contains a general ruling which include all the specific rulings stated by the scholars about the gharar which is prohibited. The ruling indicates the prohibition of consuming others property unjustly as mentioned in the above versus.

Forms of Gharar

Any bilateral transaction that comprises the following involves gharar:

· The liability of the party in the transaction is either uncertain or contingent.

· Consideration of either is not known.

· Ultimate outcome of any one party is uncertain.

· Delivery is not in the control of the obligor.

· Payment from one side is certain, but from the other side is contingent. Typical examples of gharar include the sale of fish in the water, birds in the sky, an unborn calf in its mother’s womb, a runaway animal, unripened fruits on the tree, etc. All these cases involve the sale of an item which may or may not exist. In such circumstances, to mention but a few, the fish in the sea may never be caught, the calf may be stillborn, and the fruits may never ripen. In all such cases, it is in the best interest of the trading parties to be very specific about what is being sold and for what price. The Prophet (s.a.w.) has forbidden the purchase of the catch of a diver. The prohibition in this ḥadīth pertains to a person paying a fixed price for whatever a diver may catch on his next dive. In this case, he does not know what he is paying for. On the other hand, paying a fixed price to hire the diver for a fixed period of time (where whatever he catches belongs to the buyer) is permitted. The object of this contract (the diver’s labour e.g. for one hour) is well defined. In many cases, gharar can be eliminated from contracts by carefully stating the object of sale and the price in order to eliminate unnecessary ambiguities.

Gharar in Modern Contracts

In contemporary financial transactions, the two areas where gharar most profoundly affects common practice are insurance and financial derivatives. Jurists argue against the financial insurance contract, where premiums are paid regularly to the insurance company, and the insured receives compensation for any insured losses in the event of a loss. In this case, there is a possibility that the insured may collect a large sum of money after paying only one monthly premium. On the other hand, there is also the possibility of the insured making many monthly payments without ever collecting any money from the insurance company. Since “insurance” or “security” itself cannot be considered an object of sale, this contract is rendered invalid because of the forbidden gharar. Of course, conventional insurance also suffers from prohibition due to ribā since insurance companies tend to invest significant portions of their funds in government bonds which earn them ribā. The other set of relevant contracts which are rendered invalid because of gharar are forwards, futures, options, and other derivative securities. Forwards and futures involve gharar since the object of the sale may not exist at the time the trade is to be executed. Islamic law permits certain exceptions to this rule through the contracts of salam and istiṣnāʿ. However, the conditions of those contracts make it very clear that contemporary forwards and futures are not permitted under Islamic law. Classical jurists called such contracts al-bayʿ al-muḍāf, where both the prices and the goods are to be delivered at a future date (for example, “I shall sell you this car for so much at the beginning of the next month”) and considered them unconcluded and thus, invalid. Contemporary options (e.g. “I shall sell you my house for so much if my father returns”) were also discussed by traditional jurists who called them suspended conditional sale (al-bayʿ al-muʿallaq). They have also rendered such sales invalid due to gharar.

(5) QIMĀR: CONCEPT AND FORMS

Gambling (qimār or Maysir) as well as speculation that falls under gambling in terms or Shariah is not permissible in Islamic law. IslamicMarkets.com defined Qimar/Maysir as any type of prohibited arrangement in which the acquisition of property is contingent upon the occurrence of an uncertain event, as is the case in gambling. Therefore, a Shariah financial planner must possess an understanding of the essential nature of qimār. Qimār/maysir has been clearly prohibited by Qur’ān and the Sunnah (traditions of the Holy Prophet (s.a.w.). A type of prohibited arrangement in which the acquisition of property is contingent upon the occurrence of an uncertain event, as is the case in gambling. Gambling discourages honest labour and encourages greed, materialism and discontent. It encourages ‘getrich-quick’ thinking and reckless investment of God-given resources. It is, in its essence, a form of misappropriation, which borders on stealing. Each gambler wants to get the prize money. The Qur’ān specifically bans qimār or gambling in al-Mā’idah (5:90-91): “O ye who believe! Intoxicants and gambling, sacrificing to stones, and (divination by) arrows, are an abomination, of Satan’s handiwork: eschew such (abomination) that ye may prosper Satan’s plan is (but) to excite enmity and hatred between you, with intoxicants and gambling, and hinder you from the remembrance of Allah, and from prayer: will ye not then abstain?”. Gambling has been defined as a transaction where a contractor gains contingent ownership of a countervalue. Both sides of the transaction are equal; that is, its outcome is uncertain. Consequently, there are two equal possibilities of gaining total profit or suffering total loss. For instance, it is possible that the penalty may fall on A, and it is possible that it may fall on B. All forms of transactions and deals that reflect these elements come under the domain of gambling. Hence, gambling is an activity in which the players voluntarily transfer money or something else of value amongst themselves, but this transaction is contingent upon the outcome of some future uncertain event. Examples of such activities are when A says to B: ‘If it rains today, I will give you RM100.00, and if it does not rain today, then you will have to give me RM100.00’; or two people compete in a race on the condition that the loser will have to pay the winner RM100.00.

Conditions of Qimār There are four ingredients for a transaction to be categorized as qimār:

(a) It is a transaction between two or more people;

(b) In order to gain someone else’s wealth in the transaction, one places his wealth at stake, whether actually, or by promising to pay later;

(c) Gaining another’s wealth is contingent upon some uncertain event in the future, and both possibilities of it occurring and not occurring are present;

(d) The wealth which one puts at stake is either lost completely without anything in return (one suffers a complete loss), or it brings with it some wealth of the other person without giving anything in return (the other person suffers a complete loss).

Any transaction that has the above-mentioned four elements will be considered a transaction of gambling, and hence unlawful.

Forms of Qimār

(1) The first form of gambling is when no party is obliged to pay any amount for certain; rather, the payment of each party is dependent upon an uncertain event in the future. That is the payment and consequence of the event both only be known in the future. For example, A and B compete in a race, with the promise of the loser paying the winner RM100.00. In this example, there is no certainty of payment to/from any one party; rather the payment is contingent upon winning or losing.

(2) The second form of gambling is where payment is certain for one party and uncertain for the other. The one paying for certain is actually staking his wealth, in that it may bring more wealth or it may be lost totally. This is probably the most widespread type of gambling and has many different forms.

In this category we have the prevalent forms of insurance, in that the premiums are paid for certain, whereas the return is uncertain. One may lose all the premiums paid or may receive in return more than the amount paid. This is one of the reasons why insurance has been declared unlawful.

(6). SHARIAH PERSPECTIVE ON TIME VALUE OF MONEY

It was discussed in the earlier sections on nature of money and ribā that Islamic principles dictate that money and commodity have different characteristics. The commodities can be of different qualities while money has no quality except that it is a measure of value or a medium of exchange. Therefore, all the units of money of the same denomination are equal to each other. Due to this, in an exchange of money against money, any excess amount charged against deferred payment is ribā, since the excess is charged only against time.

In contrast, a seller may take into account the time factor in fixing a higher price for his commodity in a credit sale, but the increased price is being fixed for the commodity and not exclusively for the time element. However, once a commodity is sold, the resultant debt established on the buyer may not be increased in view of any further extension granted for payment; nor could a debt be sold to another at a discounted price in view of the latter’s cash payment.

This could indicate that the Shariah admits the effect of time on the value of commodities and recognizes the innate human preference of what is in hand to what is deferred. It is permissible to place a premium on time in credit sale of commodities. However, time valuation is possible only in business and trade of goods, and not in the exchange of monetary values or loans and debts. Thus, time in itself may not be the subject matter of a contract. Negation of the economic value of time in the case of a loan means that time is treated differently in loans and sales.

Shariah accepts the value of time in sale contract. One example is in the case of deferred payment sale or BAI’ AL-MUAJJAL‘. In deferred payment sale, credit price can be higher than the cash price. This is to compensate the seller for his inability to use the assets relinquished to the buyer, when he is not taking the full price of assets sold.

Another prove that Islam accepts the concept of time value of money in sale contract is the permissibility of bayʿ al-salam. Bayʿ alsalam is sale of goods to be delivered in the future with the price paid immediately by the buyer. The price of sold item is cheaper at the point of sale compared to when the goods are delivered to the buyer in the future. The concept also applies to bayʿ al-istiṣnāʿ where the buyer of manufactured items must pay immediately upon contract conclusion whilst the manufactured items to be delivered in the future.

As far as financial planning operations are concerned, for the purpose of computation of present and future values of cash flows etc, there could be no bar to considering time value of money among other factors. This is because here the valuation only serves the purpose of making a comparison of the relative values of assets and cash flows, which could assist a person in taking prudent investment decisions etc. Such valuation itself does not result in any ribā contract. What is disapproved in Shariah is time value of money being allowed to come into active play in a transaction involving a monetary exchange or a loan, resulting in the actual occurrence of ribā.

As cleverly put forward by some, this means that what is prohibited in Shariah is monetary value of time.

(7). CALCULATION OF TIME VALUE OF MONEY

After learning about the Islamic approach to loans and interest, it is important to have an idea of how interest is explained in conventional finance. Interest is usually treated in modern commerce as a fee, paid on borrowed capital. Assets lent include money, shares, consumer goods through hire purchase, major assets such as aircraft, and even entire factories in finance lease arrangements. Interest is calculated upon the value of the assets in the same manner as upon money. Interest can be thought of as “rent on money”. For example, if you want to borrow money from the bank, there is a certain rate you have to pay according to how much you want to borrow.

The fee is explained as compensation to the lender for foregoing other useful investments that could have been made with the loaned money. These foregone investments are known as opportunity cost. Instead of the lender using the assets directly, they are advanced to the borrower. The borrower then enjoys the benefit of using the assets ahead of the effort required to obtain them, while the lender enjoys the benefit of the fee paid by the borrower for the privilege. The amount lent, or the value of the assets lent, is called the principal. This principal value is held by the borrower on credit. Interest is therefore the price of credit, not the price of money. The percentage of the principal that is paid as a fee (the interest), over a certain period of time, is called the interest rate.

Time Value of Money (TVM) is an important concept in financial planning. It can be used to compare investment alternatives and to solve problems involving loans, mortgages, leases, savings, and annuities. TVM and its application in regular financial planning will be discussed first, and thereafter its Shariah perspective will be explained.

The time value of money is based on the premise that an investor prefers to receive a payment of a fixed amount of money today, rather than an equal amount in the future, all else being equal. In particular, if one received the payment today, one can then earn interest on the money until that specified future date.

TVM is based on the concept that a dollar that you have today is worth more than the promise or expectation that you will receive a dollar in the future. Money that you hold today is worth more because you can invest it and earn interest. After all, you should receive some compensation for foregoing spending. For instance, one can invest RM1.00 for one year at a 6% annual interest rate and accumulate RM1.06 at the end of the year. You can say that the future value of RM1.00 is RM1.06 given a 6% interest rate and a one year period. It follows that the present value of the RM1.06 you expect to receive in one year is only RM1.00.

A key concept of TVM is that a single sum of money or a series of equal, evenly spaced payments or receipts promised in the future can be converted to an equivalent value today. Conversely, you can determine the value to which a single sum or a series of future payments will grow at some future date.

Time value computation is done with reference to principal and interest.

Principal is the amount the client has in possession, through savings, investments or borrowings. In savings and investments, the principal sum is an asset, while if borrowed, it is a liability (it is an asset for the lender).

Interest denotes the monetary return for the person who saved, invested or lent the principal sum. Interest is also the cost of borrowing money.

Interest rate is the price a borrower pays for the use of money he does not own, and the return a lender receives for deferring the use of funds, by lending it to the borrower. Interest rates are normally expressed as a percentage rate over the period of one year.

To calculate interest, three elements should be known:

(i). Amount of principal

(ii). Rate of interest

(iii). The period

Therefore: Interest = Amount of Principal X Interest Rate X Period Example: If a bank pays 10% interest per year, the annual interest on a deposit of RM 50,000 is RM 5000 (RM 50,000 X 10% X 1).

(1) Simple Interest

Simple interest is calculated on the original principal only. Accumulated interest from prior periods is not used in calculations for the following periods. Simple interest is normally used for a single period of less than a year, such as 30 or 60 days.

Simple Interest = p X i X n

Where:

p = principal (original amount borrowed or loaned)

i = interest rate for one period

n = number of periods

Example: You borrow RM10,000 for 3 years at 5% simple annual interest. Interest = p X i X n = 10,000 X .05 X 3 = 1,500

Example 2: You borrow RM10,000 for 60 days at 5% simple interest per year (assume a 365 day year). Interest = p X i X n = 10,000 X .05 X (60/365) = 82.1917

(2) Compound Interest

Compound interest is calculated for each period on the original principal and all interest accumulated during past periods. Although interest may be stated as a yearly rate, the compounding periods can be yearly, semiannually, quarterly, or even continuously.

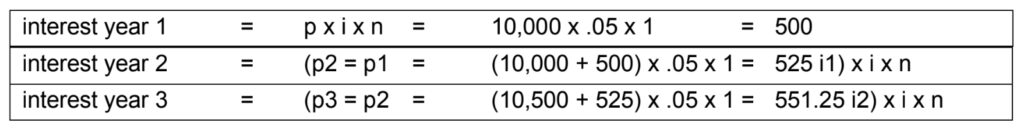

You can think of compound interest as a series of back-to-back simple interest contracts. The interest earned in each period is added to the principal of the previous period to become the principal for the next period. For example, you borrow RM10,000 for three years at 5% annual interest compounded annually:

Total interest earned over the three years = 500 + 525 + 551.25 = 1,576.25. Compare this to 1,500 earned over the same number of years using simple interest.

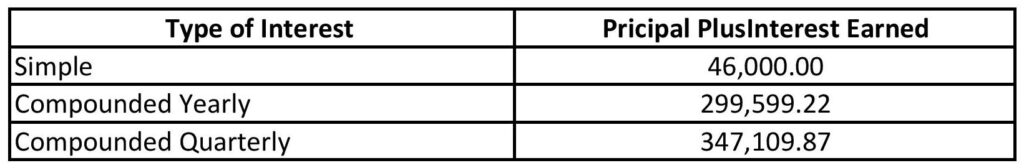

The power of compounding can have an astonishing effect on the accumulation of wealth. This table shows the results of making a onetime investment of RM10,000 for 30 years using 12% simple interest, and 12% interest compounded yearly and quarterly.

(3) Nominal Interest Rate

This is the rate that is stated in a loan contract. It is the stated rate or the contractual rate.

E.g. Interest is paid by X bank on deposits at 8% per annum. This is the nominal rate.

(4) Effective Interest Rate

Effective interest rate takes into consideration whether the nominal rate is subject to compounding. It is an investment’s annual rate of interest when compounding occurs more often than once a year.

Ieff = [1 + i/n]n – 1

Where:

Ieff = Effective interest rate

I = Stated nominal interest rate

n = Number of compounding periods within a year, e.g. if quarterly, n = 4 Consider a stated annual rate of 10%.

Compounded yearly, this rate will turn RM1000 into RM1100. However, if compounding occurs monthly, RM1000 would grow to RM1104.70 by the end of the year, rendering an effective annual interest rate of 10.47%.

Basically, the effective annual rate is the annual rate of interest that accounts for the effect of compounding.

(5) Present Values and Future Values

For comprehending present and future values pertaining to cash flows, it is necessary to know the principles related to compounding and discounting.

Compounding is the process of computing how the future values of an amount will become at the end of a selected period if it grows at certain assumed interest rates.

Discounting is the reverse of this process. It shows the value of a future amount in today’s terms, reducing at a certain assumed interest rate over the relevant period.

Periods per annum are the frequency based on which interest is applied in a calendar year in the compounding or discounting process.

Compounding and discounting are influenced by some factors including the following:

(i). The frequency or number of periods that interest is charged, such as annual, semiannual, and quarterly. An increase in the number of compounding periods results in an increase of the future value (see below) and vice versa; increase in the discounting frequency results in a decrease of the present value (see below) and vice versa.

(ii). The interest rates assumed in the compounding or discounting process. An increase in the interest rate increases the future value and vice versa; an increase of the interest rate decreases the present value and vice versa.

(a) Present Value of a single sum

Present Value is an amount today that is equivalent to a future payment, or series of payments, that has been discounted by an appropriate interest rate. Since money has time value, the present value of a promised future amount is worth less the longer you have to wait to receive it. The difference between the two depends on the number of compounding periods involved and the interest (discount) rate.

The relationship between the present value and future value can be expressed as:

PV = FV [ 1 / (1 + i)n ]

Where:

PV = Present Value

FV = Future Value

i = Interest Rate per Period

n = Number of Compounding Periods

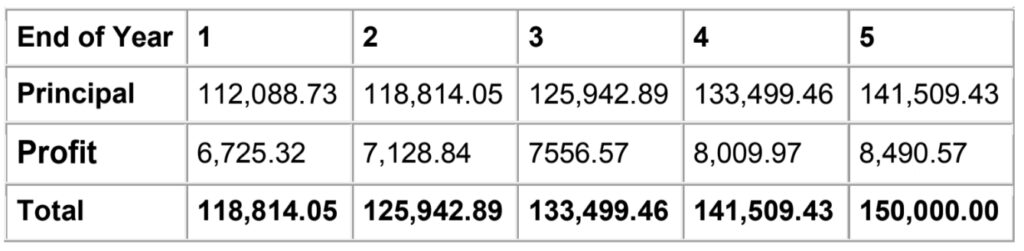

Example: You want to buy a house 5 years from now for RM150,000. Assuming a 6% interest rate compounded annually, how much should you invest today to yield RM150,000 in 5 years?

FV = 150,000

i = 0.06

n = 5

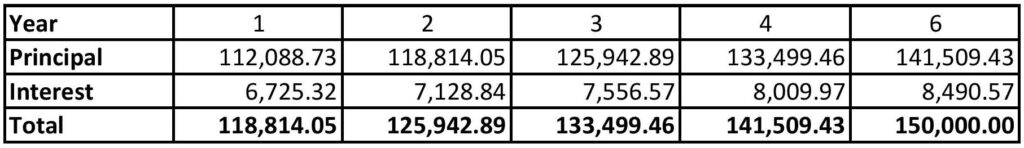

PV = 150,000 [ 1 / (1 + .06)5 ] = 150,000 (1 / 1.3382255776) = 112,088.73

Example 2: You find another financial institution that offers an interest rate of 6% compounded semiannually. How much less can you deposit today to yield RM150,000 in five years?

Interest is compounded twice per year, so you must divide the annual interest rate by two to obtain a rate per period of 3%. Since there are two compounding periods per year, you must multiply the number of years by two to obtain the total number of periods.

FV = 150,000

i = .06 / 2 = .03

n = 5 X 2 =10

PV = 150,000 [ 1 / (1 + .03)10] = 150,000 (1 / 1.343916379) = 111,614.09

(b) Present Value of Annuities

An annuity is a series of equal payments or receipts that occur at evenly spaced intervals. Leases and rental payments are examples. The payments or receipts occur at the end of each period for an ordinary annuity while they occur at the beginning of each period for an annuity due.

Present Value of an Ordinary Annuity

The Present Value of an Ordinary Annuity (PVoa) is the value of a stream of expected or promised future payments that have been discounted to a single equivalent value today. It is extremely useful for comparing two separate cash flows that differ in some ways. PV-oa can also be thought of as the amount you must invest today at a specific interest rate so that when you withdraw an equal amount each period, the original principal and all accumulated interest will be completely exhausted at the end of the annuity. The Present Value of an Ordinary Annuity could be arrived at by calculating the present value of each payment in the series using the present value formula and then summing the results. A more direct formula is:

PVoa = PMT [(1 – (1 / (1 + i)n )) / i]

Where:

PVoa = Present Value of an Ordinary Annuity

PMT = Amount of each payment

i = Discount Rate Per Period

n = Number of Periods

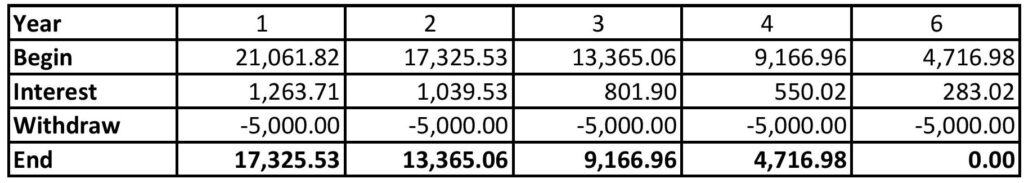

Example 1: What amount must you invest today at 6% compounded annually so that you can withdraw RM5,000 at the end of each year for the next 5 years?

PMT = 5,000

I = 0.06

n = 5

PVoa = 5,000 [(1 – (1/(1 + .06)5 )) / .06] = 5,000 (4.212364) = 21,061.82

Example 2: In practical problems, you may need to calculate both the present value of an annuity (a stream of future periodic payments) and the present value of a single future amount:

For example, a software dealer offers to lease a program to you for RM50 per month for two years. At the end of two years, you have the option to buy the program for RM500. You will pay at the end of each month. He will sell the same system to you for RM1,200 cash. If the going interest rate is 12%, which is the better offer?

You can treat this as the sum of two separate calculations:

1. The present value of an ordinary annuity of 24 payments at RM50 per monthly period, plus

2. The present value of RM500 paid as a single amount in two years.

PMT = 50 per period

i = 0.12 /12 = 0.01 Interest per period (12% annual rate / 12 payments per year)

n = 24 number of periods

PVoa = 50 [(1 – (1/(1.01)24)) / .01] = 50 [(1- (1 / 1.26973)) /.01] = 1,062.17

FV = 500 Future value (the lease buy out)

i = 0.01 Interest per period

n = 24 Number of periods

PV = FV [ 1 / (1 + i)n ] = 500 ( 1 / 1.26973 ) = 393.78

The present value (cost) of the lease is RM1,455.95 (1,062.17 + 393.78). So if taxes are not considered, you would be RM255.95 better off paying cash right now if you have it.

Present Value of an Annuity Due (PVad)

The Present Value of an Annuity Due is identical to an ordinary annuity except that each payment occurs at the beginning of a period rather than at the end. Since each payment occurs one period earlier, we can calculate the present value of an ordinary annuity and then multiply the result by (1 + i).

PVad = PVoa (1+i)

Where:

PV-ad = Present Value of an Annuity Due

PV-oa = Present Value of an Ordinary Annuity

i = Discount Rate Per Period

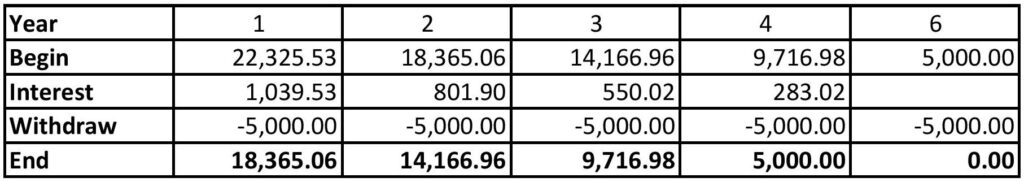

Example: What amount must you invest today at 6% interest rate compounded annually so that you can withdraw RM5,000 at the beginning of each year for the next 5 years?

PMT = 5,000

i = 0.06

n = 5

PVoa = 21,061.82 (1.06) = 22,325.53

(c) Future Value of a Single sum

Future Value is the amount of money that an investment made today (the present value) will grow to by some future date. Since money has time value, we naturally expect the future value to be greater than the present value. The difference between the two depends on the number of compounding periods involved and the going interest rate.

The relationship between the future value and present value can be expressed as:

FV = PV (1 + i)n

Where:

FV = Future Value

PV = Present Value

i = Interest Rate per Period

n = Number of Compounding Periods

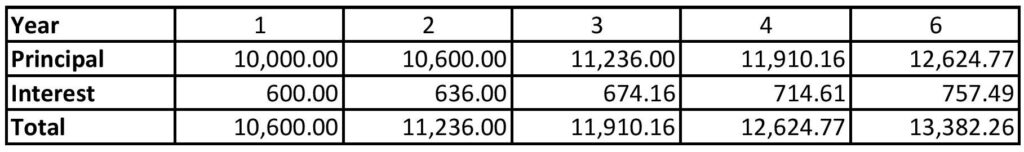

Example 1: You can afford to put RM10,000 in a savings account today that pays 6% interest compounded annually. How much will you have 5 years from now if you make no withdrawals?

PV = 10,000

i = 0.06 n = 5

FV = 10,000 (1 + .06)5 = 10,000 (1.3382255776) = 13,382.26

Example 2: Another financial institution offers to pay 6% compounded semiannually. How much will your RM10,000 grow to in five years at this rate? Interest is compounded twice per year so you must divide the annual interest rate by two to obtain a rate per period of 3%. Since there are two compounding periods per year, you must multiply the number of years by two to obtain the total number of periods.

PV = 10,000

i = 0.06 / 2 = 0.03

n = 5 X 2 = 10

FV = 10,000 (1 + .03)10 = 10,000 (1.343916379) = 13,439.16

(d) Future Value of Annuities

An annuity is a series of equal payments or receipts that occur at evenly spaced intervals. Leases and rental payments are examples. The payments or receipts occur at the end of each period for an ordinary annuity while they occur at the beginning of each period for an annuity due.

Future Value of an Ordinary Annuity

The Future Value of an Ordinary Annuity (FVoa) is the value that a stream of expected or promised future payments will grow to after a given number of periods at a specific compounded interest. The Future Value of an Ordinary Annuity could be arrived at by calculating the future value of each individual payment in the series using the future value formula and then summing the results. A more direct formula is:

FVoa = PMT [((1 + i)n – 1) / i]

Where:

FVoa = Future Value of an Ordinary Annuity

PMT = Amount of each payment

i = Interest Rate per Period

n = Number of Periods

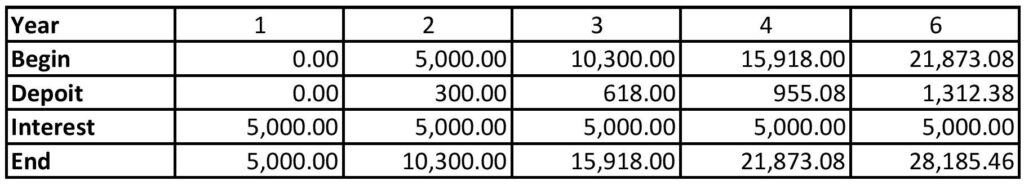

Example 1: What amount will accumulate if we deposit RM5,000 at the end of each year for the next 5 years?

Assume an interest of 6% compounded annually.

PV = 5,000

i = 0.06

n = 5

FVoa = 5,000 [(1.3382255776 – 1) /.06] = 5,000 (5.637092) = 28,185.46

Example 2: In practical problems, you may need to calculate both the future value of an annuity (a stream of future periodic payments) and the future value of a single amount that you have today. For example, you are 40 years old and have accumulated RM50,000 in your savings account. You can add RM100 at the end of each month to your account which pays an interest rate of 6% per year. Will you have enough money to retire in 20 years?

You can treat this as the sum of two separate calculations:

1. the future value of 240 monthly payments of RM100 plus

2. the future value of the RM50,000 now in your account.

PMT = RM100 per period

i = 0.06 /12 = 0.005 Interest per period (6% annual rate / 12 payments per year

n = 240 periods

FVoa = 100 [ (3.3102 – 1) /.005 ] = 46,204

+

PV = 50,000 Present value (the amount you have today)

i = 0.005 Interest per period

n = 240 Number of periods

FV = PV (1+i)240 = 50,000 (1.005)240 = 165,510.22

After 20 years you will have accumulated RM211,714.22 (46,204.00 + 165,510.22).

Future Value of an Annuity Due (FVad)

The Future Value of an Annuity Due is identical to an ordinary annuity except that each payment occurs at the beginning of a period rather than at the end. Since each payment occurs one period earlier, we can calculate the present value of an ordinary annuity and then multiply the result by (1 + i).

FVad = FVoa (1+i)

Where:

FVad = Future Value of an Annuity Due

FVoa = Future Value of an Ordinary Annuity

i = Interest Rate per Period

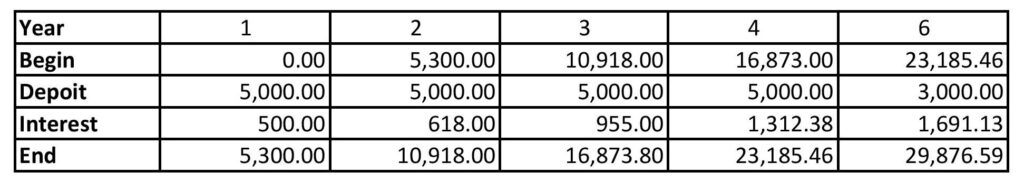

Example: What amount will accumulate if we deposit RM5,000 at the beginning of each year for the next 5 years? Assume an interest of 6% compounded annually.

PV = 5,000

i = 0.06

n = 5

FVoa = 28,185.46 (1.06) = 29,876.59

7.6 Net Present Value (NPV)

NPV of an investment is the present value of the stream of cash inflows minus the present value of the stream of cash outflows. Both values are computed based on an assumed rate of interest or discount rate, which is normally the minimum rate that is acceptable to the investor based on the risk of the investment. NPV = PV of Cash Inflows – PV of Cash Outflows If NPV is positive, the investment is sound; if negative, it is unprofitable.

7.7 Internal Rate of Return (IRR)

IRR of an investment is the interest rate that equates the present value of the stream of cash inflows to the present value of the stream of cash outflows. The IRR is the interest rate that makes the net present value of all cash flow equal to zero. In financial analysis terms, the IRR can be defined as a discount rate at which the present value of a series of investments is equal to the present value of the returns on those investments. Generally speaking, the higher a project’s internal rate of return, the more desirable it is to undertake the project.

7.8 Amortization

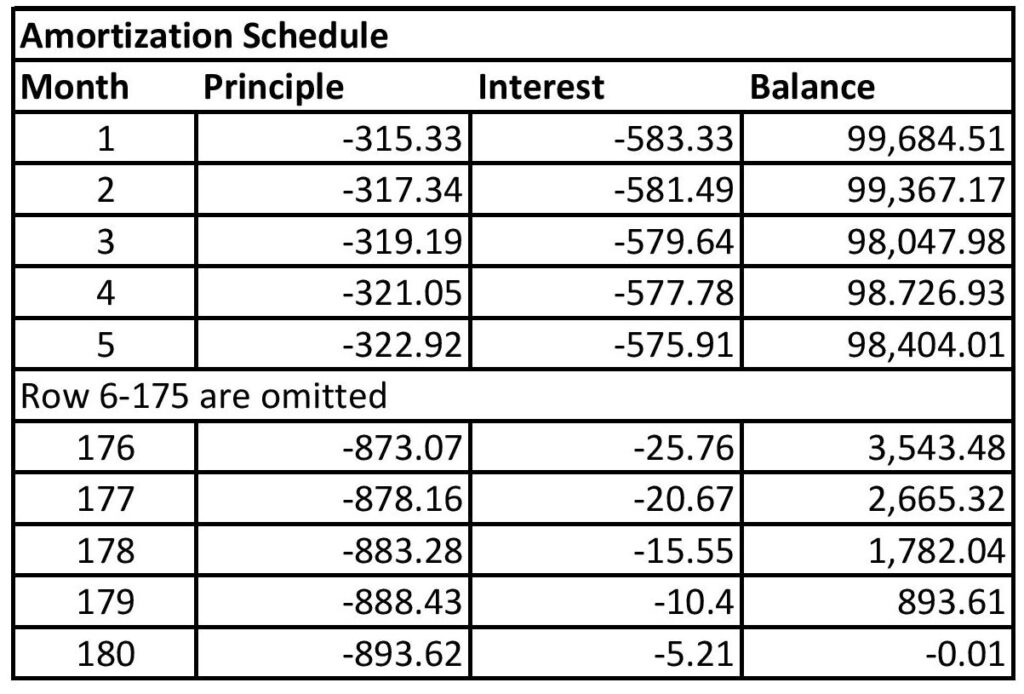

Amortization is a method for repaying a loan in equal installments. Part of each payment goes toward interest due for the period and the remainder is used to reduce the principal (the loan balance). As the balance of the loan is gradually reduced, a progressively larger portion of each payment goes toward reducing principal. For example, the 15 and 30 years fixed-rate mortgages are usually fully amortized loans. To pay off a RM100,000, 15 years, 7%, fixed-rate mortgage, a person must pay RM898.83 each month for 180 months (with a small adjustment at the end to account for rounding). RM583.33 of the first payment goes toward interest and RM315.50 is used to reduce principal. But by the 179th payment, only RM10.40 is needed for interest and RM888.43 is used to reduce the principal.

An amortization schedule is a table with a row for each payment period of an amortized loan. Each row shows the amount of the payment that is needed to pay interest, the amount that is used to reduce principal, and the balance of the loan remaining at the end of the period.

The first and last 5 months of an amortization schedule for a RM100,000, 15 year, 7%, fixed-rate mortgage will look like this:

Amortization Schedule Month Principal Interest Balance

Negative amortization occurs when the payment is not large enough to cover the interest due for a period. This will cause the loan balance to increase after each payment – a situation that should certainly be avoided. This might occur, for instance, if the rate of the adjustable-rate loan increases, but the payment does not.

Self-Assessment

Circle the letter of the correct choice for each of the following:

1. Which of the following is the type of riba that relates to the trade of goods of unequal quantities or unequal qualities?

A. Riba al-Nasiah

B. Riba al-fadl

C. Riba Al-Quran

D. Riba Al-Jahiliyyah

2. The following are examples of the application of discounting in project evaluation EXCEPT:

A. Net Present Value (NPV)

B. Internal Rate of Return (IRR)

C. Payback period

D. Discounted cash flow

3. The following statements on time value of money are TRUE EXCEPT:

A. Time belongs to Allah S.W.T. He will reward the reduction of money due to time factor.

B. The cost of capital used to compensate the loss of the value of money is the interest rate.

C. Time value of money is allowed as long as contractual reward determined ex-ante is stated in exchange for a loan.

D. Uncertainty of future events leads to the usage of rate of return on equity as the cost of capital.

4. Shariah prohibits all of these EXCEPT:

A. Risk taking B. Maysir C. Gharar D. Riba

5. An investor would like to know the amount he would be receiving if he invests a sum of money at a certain rate of return. Which concept of discounting is to be used?

A. Future Value

B. Present Value of Annuity

C. Present Value of a Perpetuity

D. Present Value

6. Gharar exists in the following conditions EXCEPT:

A. Participative Islamic insurance B. Insurance

C. Buying goods that do not exist at the time of purchase

D. When the price of goods is not specified

7. Which of the following DOES NOT amount to Qimar?

A. Buying lotteries.

B. Buying shares with the hope that their prices will increase in the future.

C. Selling goods to potential sellers using the random mechanism.

D. Betting on palm oil futures, buying low to sell it high in the future.

8. Insurance contract is haram because the contract contravenes the following Shariah principles, EXCEPT:

A. It involves maysir as payments will be paid to insurance holders upon certain occurrences, such as death or accidents.

B. It involves riba related activities.

C. It amounts to gharar as the price is determined via the use of uncertain variables.

D. Saving through insurance provides low percentage of returns as compared to other types of investment.

9. What is the opinion of money in the Shariah?

A. Money has no intrinsic utility.

B. Money cannot be a measure of value or a medium of exchange.

C. Money can be exchanged at different values.

D. Money of a currency can be exchanged with other currencies in the forward market.

10. You want to buy a house 5 years from now for RM150,000. Assuming a 6% rate compounded annually, how much should you invest today to yield RM150,000 in 5 years?

FV = 150,000

i = 0.06

n = 5

PV = 150,000 [ 1 / (1 + .06)5 ] = 150,000 (1 / 1.3382255776) = 112,088.73

The above calculation is

A. Correct in all years

B. Correct in 5th years only

C. Correct in the 1st year only

D. All the above

Answer: 1-b, 2-c, 3-b, 4-a, 5-d, 6-a, 7-b, 8-d, 9-a,10-a