Contents

Preview

About this topic

Topic objectives

Framework

Dis6rdsure-based regulation

Corporate Governance

Principle of Regulations

Disclosure information

Prudential capital requirements

Transparency

Market manipulation and other unfair trading practices

Management of large exposures, default risk and market disruption

Single Licensing Framework for the Capital Markets

Appendices

IVan Boesky’s choice

Self Assessment

Exercises

Preview

About this topic

This topic sets out the rationale for regulatory emphasis on compliance — the need for self-regulation and corporate governance in a disclosure-based regulatory environment.

We describe the basic principles which underlie this regulatory approach to Malaysia’s capital market. In so doing, we focus on the principles existing in the relevant Securities Commission Malaysia’s regulations and guidelines and rules of the exchanges, which include full disclosure of information, prudential capital requirements, transparency, market manipulation and other unfair trading practices and management of risk and

market disruption. We conclude with a brief discussion of the licensing framework for intermediaries in the Malaysian capital market.

Topic Objectives

At the end of this topic, you should be able to:

(a) describe the importance of corporate governance under disclosure-based

regulation

(b) explain the principles of capital market regulation and how they can be addressed in terms of compliance

(c) explain the licensing framework for intermediaries in the capital market

Framework

Disclosure-based regulation

Disclosure-based regulation (DBR) is integral to the Securities Commission Malaysia’s (SC) aim to ensure that the Malaysian capital market is transparent, efficient, sound and credible, and that the conduct of market participants is responsible.

DBR focuses on whether the applicable standards of disclosure are complied with and whether due diligence is performed by the issuers or offerors of securities and their advisers in respect of the accuracy and completeness of the information disclosed by them. The regulator, under DBR, does not assess or pass the investment merits or quality of any securities to be issued or offered. Instead, it is the investors who have the

responsibility to assess the potential risks and rewards. The role of the SC is to focus on the disclosures made and the quality of the disclosures to ensure that they are full, timely and accurate. The regulatory emphasis is on full disclosure and education.

In addition, DBR provides for a continuous flow of information about listed companies so that the secondary market is adequately informed and operates more efficiently and in a transparent manner.

The standards of disclosure, which affect market integrity and investor protection, and due diligence, corporate governance and accountability apply equally in the context of compliance.

Corporate governance

Corporate governance is the process and structure whereby the business and affairs of a firm should be directed and managed, as well as the observance of codes of best practice and standards. The strengthening of the corporate governance mechanism in companies is a key component of the shift to disclosure-based regulation. Good corporate governance involves essentially the promotion of shareholders’ rights and responsibilities, transparency in the management of the company and investor education.

The High Level Finance Committee Report defines corporate governance as:

The process and structure used to direct and manage the business and affairs of the company towards enhancing business prosperity and corporate accountability with the ultimate objective of realising long-term shareholder value whilst taking into account the interest of other stakeholders.

In July 2011, the SC launched its five-year Corporate Governance Blueprint which provides the action plan to raise the standards of corporate governance. This includes strengthening self and market discipline and promoting greater internalisation of the culture of good governance. It engenders a shift in corporate governance culture from mere compliance with rules to one that more fittingly captures the essence of good corporate governance, namely a deepening of the relationship of trust between firms and stakeholders.

The Malaysian Code on Corporate Governance 2012 is the first deliverable of the Corporate Governance Blueprint. It sets out the broad principles and specific recommendations on structures and processes which firms should adopt in making good corporate governance an integral part of their business dealings and culture.

Principles of Regulations

Disclosure of information

One of the aims of regulation is to ensure that markets are fair. By fairness, we mean that market participants are able to compete on a level playing field, i.e. no one group of individuals or corporations is advantaged at the expense of another, and there are equal trading opportunities for everyone.

Specifically, disclosure of information refers to providing investors with the necessary information to enable them to make informed investment decisions. It relates directly to the objectives of investor protection and the establishment of fair, efficient and transparent markets.

Disclosure is particularly important when advertising an offer of securities, especially in relation to the interests of directors in the equities.

Prudential capital requirements

Prudential standards and requirements have been adopted for firms to provide professionally managed and financially strong conduits for investors to access the markets. The capital adequacy requirements refine the prudential benchmark for maintaining better market integrity at the level Of the exchange and the clearing house.

These requirements include:

(a) Maintenance of a minimum amount of paid-up capital to support its business.

(b) Standards for the classification and treatment of interest on non-performing accounts.

(c) Standards to ensure capital adequacy, that is that the liquid capital of a firm is sufficient to cover its total measured risks. The capital adequacy requirements are a risk-based financial monitoring tool, and necessitate management and assessment of the risk of the operations of firms on a daily basis, including actual and contingent short-term liabilities.

(c) Rules to protect clients’ assets relating to a firm’s dealings with its clients’ assets and minimum criteria for margin financing activities.

(d) Reporting of financial position to the exchange and/or clearing house.

The Rules of Bursa Malaysia Securities Berhad addresses both liquidity and solvency issues together with risks faced by a firm. Liquidity is represented by liquid capital in the nearest form, solvency is represented by liquid margin after accounting for a series of identified risks inherent in the operating environment and the composition of liquid

capital. These risks are operational risk, position risk, counterparty risk, large exposure risk and underwriting risk.

Capital adequacy requirements:

(a) promote enhanced risk management by enabling firms to identify the capital available to cover risks;

(b) provide a proactive mechanism for firms allowing them to quantify, manage and address business risks; and

(c) improve and enhance monitoring.

Firms must also satisfy the minimum financial requirements prescribed by the regulators as follows:

(i) Dealing in securities

Capital Markets Services Licence holders carrying the regulated activity of dealing in securities are required by the SC to maintain the following minimum financial requirements:

Stockbroking company (other than Investment Bank or Universal Broker)

(a) Minimum paid-up capital of RM20 million

(b) Minimum shareholders’ funds of RM20 million to be maintained at all times

(c) Minimum capital adequacy ratio of 1.2 or any other financial requirement as determined by the SC from time to time

Investment bank

(a) Minimum capital funds unimpaired by losses of RM500 million or minimum capital funds unimpaired by losses of RM2 billion on a banking group basis

(b) Minimum risk-weighted capital ratio of 8%

Universal broker

(a) Minimum paid-up capital of RM100 million

(b) Minimum shareholders’ funds of RM100 million to be maintained at all

times

(c) Minimum capital adequacy ratio of 1.2 or any other financial requirement as determined by the SC from time to time

Issuing house

(a) Minimum shareholders’ funds of RM2 million to be maintained at all times

Dealing in unit trust products

(a) Applicable to an applicant dealing in unit trust products as a principal business (for own products and/or third party products). Such companies may use a nominee system.

(i) Minimum paid-up capital of RM5 million

(ii) Minimum shareholders’ funds of RM5 million to be maintained at all

times.

(b) Applicable to persons licensed to carry on the regulated activity of financial planning and who want to deal in unit trust products following a financial plan.

(i) Minimum paid-up capital of RM100,000

(ii) Minimum shareholders’ funds of RM100,000 to be maintained at all

times

Dealing in unlisted debt securities

Advising on Corporate Finance (to carry out the activity of principal

adviser)

(a) Minimum shareholders’ funds of RM100 million to be maintained at all

times

(ii) Dealing in derivatives

Both the SC and Bursa Malaysia Derivatives Berhad requires a Trading Participant to maintain a minimum paid-up capital of RM5 million and a minimum adjusted net capital of RM500,000 or 10% of aggregate margins required, whichever is higher.

(iii) Fund Management

Capital Markets Services Licence holders carrying the regulated activity of fund management are required by the SC to maintain minimum financial requirements as follows:

Portfolio Management

(a) Minimum paid-up capital of RM2 million

(b) Minimum shareholders’ funds of RM2 million to be maintained at all times

Business Trust

(a) No specific paid-up capital

Real Estate Investment Trusts

(a) Minimum shareholders’ funds of RM1 million at all times

Self-assessment 1

Exercise

1. Select from the following the minimum paid-up capital requirement for a

stockbroking company.

A. RM2 million

B. RM5 million

C. RM10 million

D. RM20 million

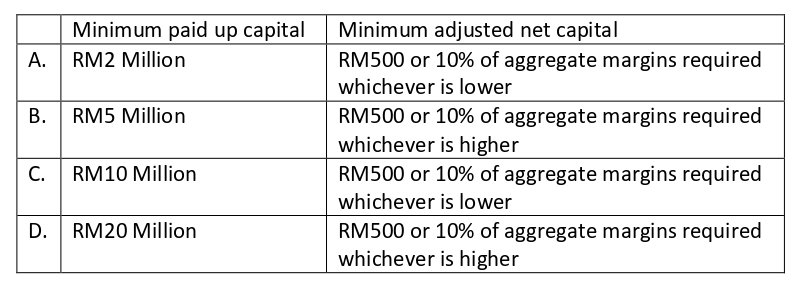

2. Select from the following the minimum financial requirements to be

maintained by Trading Participants.

Answer: B

3. Which of the following statements are TRUE of the minimum financial

requirements to be maintained by a firm licensed for fund management in

relation to portfolio management?

I. Minimum paid-up capital of RM500,000

II. Minimum paid-up capital of RM2 million

III. Minimum shareholders’ funds of RM100,000

IV. Minimum shareholders’ funds of RM2 million

A. I and III only

B. I and IV only

C. II and III only

D. II and IV only

Transparency

The rules of the exchanges set parameters designed to achieve greater clarity, transparency and consistency in the conduct of business of firms. Transparency connotes exchanges which are efficient and in which there exists legal certainty. The key areas are:

(a) best business practice

(b) dealing in securities/derivatives

(c) rules on trading

(d) delivery and settlement

(e) financial resources and accounting requirements

(f) audit regulations

(g) disciplinary actions.

Also aimed at enhancing transparency in dealing are the requirements for firms to take all reasonable measures to know their clients (particularly when the client deals on behalf of other persons) and for all trading to take place on the market (i.e. any off-

market trading can only be undertaken in accordance with the business rules of the exchange).

Self-assessment

Exercise 2

1. The rules which restrict trading by staff and directors of firms aim to avoid breaching duties owed to clients. Which of the following are the duties owed by firms to its clients?

I. act honestly and in the best interest of its clients

II. observe professional standards of integrity and fair dealing

III. to give precedence to client orders ahead of its own orders

IV. ensure the suitability of recommended transaction to the client

A. I and III only

B. II and IV only

C. I, III, and IV only

D. All of the above

Market manipulation and other unfair trading practices

The expression “fairness” is sometimes also taken to encompass the notion of investor protection (such as the elimination of fraud and manipulation, and the protection of uninformed investors against exploitation by insiders).

The trading offences under the legislation are designed to deter undesirable or fraudulent practices. They also discourage and prevent unfair use of advantageous positions and price distortions. The integrity and efficiency of the markets should rely solely on the existence of the natural forces of supply and demand.

The regulators strictly regulate trading by employees. Such transactions require approval and must be properly recorded. The accounts kept of such trading need to be subject to regular monitoring and review. The SC’s Guidelines on Market Conduct and Business Practices for Stockbrokers and Licensed Representatives relates to the standards expected of stockbrokers, their representatives and where applicable, their staff, in

market and business conduct.

The SC also promotes professionalism, ethical standards and responsible conduct among fund management companies and their representatives and employees and to this effect, had stipulated the core principles to be complied with by fund management companies in its Guidelines on Compliance Function for Fund Management Companies.

Perhaps the most widely known form of unfair trading is insider trading. Insider trading is an issue of which all employees need to be aware. It is of particular importance in corporate finance where staff is more likely to be in possession of non-public price sensitive information.

One of the best known examples is that of Ivan Boesky and the information he received from an employee of Drexel Burnham Lambert which was used indiscriminately. This is discussed in Appendix 1.

Management of large exposures, default risk and market disruption

The expression “large exposure” refers to an open position that is sufficiently large to pose a risk to the market or to a clearing house. The Rules of Bursa Malaysia Securities Berhad defines Large Exposure Risk as follows:

Large exposure Risk means the risks a participating organisation is exposed to from a proportionally large exposure to:

(a) a particular client or counterparty;

(b) a single issuer of debt securities;

(c) a single equity.

Market authorities and the firm, therefore, must monitor large exposures and share information to permit appropriate assessment of risk. See Rules of Bursa Securities Berhad for the principles applicable in calculating Large Exposure Risk Requirement.

The global financial crisis in 2007-2009 also highlighted the need for regulation of Over-the-Counter (OTC) products. Regulators globally are looking at reforms to strengthen oversight of OTC products. To promote transparency in the OTC derivatives market, the SC had amended and included a new definition in the Capital Markets & Services Act 2007 on derivatives and has made “dealing in derivatives” as a regulated activity.

In addition, the SC has also announced that a framework will be established for the reporting of OTC derivatives contracts to a trade repository.

Single Licensing Framework for the Capital Markets

The Capital Markets & Services Act 2007, which was enforced on 28 September 2007, introduces a single licensing regime for capital market intermediaries. Under this regime, a capital market intermediary will only need one licence to carry on the business in any one or more of the regulated activities set out in Schedule 2 of the Capital Markets & Services Act 2007, as follows:

(a) dealing in securities;

(b) dealing in derivatives;

(c) fund management;

(d) dealing in private retirement schemes;

(e) advising on corporate finance;

(f) investment advice; and

(g) financial planning.

Under the SC’s Licensing framework, both the firm and the individuals representing the firm who carry out the regulated activity would require a licence. Licence granted to the firm is the “Capital Markets Services Licence” and licence granted to individuals is the “Capital Markets Services Representative’s Licence”.

Licensing ensures an adequate level of investor protection, including the provision of sufficient safeguards to protect investors from default by market intermediaries or problems arising from the insolvency of such intermediaries. More importantly, it instils confidence among investors that the firms and people they deal with will treat them fairly and are efficient, honest and financially sound.

Through its authority to issue licences, the SC regulates the capital markets by ascertaining the fitness and propriety of companies and individuals applying for licences.

In considering whether an applicant is fit and proper to hold a licence, the SC takes into account the following factors:

(a) Probity

(b) Ability to perform such functions efficiently, honestly and fairly

(c) Financial status

(d) Reputation, character, financial integrity and reliability

Electronic Licensing Application

All licensing applications, except for applications for a new Capital Markets Services Licence, are to be made online to the SC via the Electronic Licensing Application (ELA) system.

All Capital Markets Services Licence holders, must, within three months of being licensed, apply to the SC for access to the ELA. Capital Markets Services Licence holders will be required to sign the “Acceptance of Terms and Conditions” with the SC.

On the anniversary of the grant of licence by the SC, all Capital Markets Services Licence and Capital Markets Services Representative’s Licence holders are required to submit the Anniversary Reporting for Authorisation of Activity Form (ARAA) via ELA to the SC. In addition, any change to particulars of the Capital Markets Services Licence or Capital

Market Services Representative’s Licence holder may require SC approval or notification via ELA as prescribed under the SC’s Licensing Handbook.

Note that all submissions under ELA are required to be printed out and signed by the relevant authorised persons (in the case of a submission by a Capital Markets Services Licence holder), the relevant representative (in the case of a submission by a Capital Market Services Representative’s Licence holder) or the relevant registered person (in the case of a submission by a registered person), before the application or notification, as the case may, is submitted to the SC through ELA. The particulars appearing on the printed copy shall be the same as that submitted through ELA.|

The printed copy of all submissions together with the supporting documents, shall be kept by the firm and/or the relevant person at the business address or the principal address, or a designated place which has been approved by the SC, at all times for as long as the person is licensed or is in the employment of the firm, and for the period of

seven (7) years after the person leaves the firm.

All information submitted to the SC through the HA must be true and accurate. Hence, a firm must have in place the necessary policies and procedures to ensure that information submitted via ELA on behalf of its representatives and/or registered persons is true and accurate.

APPENDIX 1

Ivan Boesky’s choice

Securities Institute of Australia.

Reproduced with permission.

In 1985 Ivan Boesky was known as the king of the arbitragers’, a specialised form of investment in the shares of companies that were the target of takeover offers…

His personal fortune was estimated at between $150 million and $200 million. Boesky had achieved both a formidable reputation, and a substantial degree of respectability…

‘Ivan said one colleague, ‘could get any Chief Executive Officer in the country off the toilet to talk to him at seven o’clock in the morning’…

At the height of his success, Boesky entered into an arrangement for obtaining inside information from Dennis Levine. Levine, who was himself earning around $3 million annually in salary and bonuses, worked at Drexel Burnham Lambert, the phenomenally successful Wall Street firm that dominated the ‘junk bond’ market. Since junk bonds were the favoured way of raising funds for takeovers, Drexel was involved in almost every major takeover battle, and Levine was privy to information that, in the hands of

someone with plenty of capital, could be used to make hundreds of millions of dollars, virtually without risk.

The ethics of this situation are not in dispute. When Boesky was buying shares on the basis of the information Levine gave him, he knew that the shares would rise in price. The shareholders who sold to him did not know that, and hence sold the shares at less than they could have obtained for them later, if they had not sold. If Drexel’s client was someone who wished to take a company over, then that client would have to pay more for the company if the news of the intended takeover leaked out, since Boesky’s purchases would push up the price of the shares. The added cost might mean that the bid to take over the target company would fail; or it might mean that, though the bid succeeded, after the takeover more of the company’s assets would be sold off, to pay for the increased borrowings needed to buy the company at the higher price. Since Drexel, and hence Levine, had obtained the information of the intended takeover in confidence from their clients, for them to disclose it to others who could profit from it, to the disadvantage of their clients, was clearly contrary to all accepted professional ethical standards… Boesky also knew that trading in inside information was illegal. Nevertheless, in 1985 he went so far as to formalise the arrangement he had with Levine, agreeing to pay him 5 percent of the profits he made from purchasing shares about which Levine had given him information.

Why did Boesky do it? Why would anyone who has $150 million, a respected

position in society… risk his reputation, his wealth, and his freedom by doing something that is obviously neither legal or ethical? Granted, Boesky stood to make very large sums of money from his arrangement with Levine. The Securities and Exchange Commission was later to describe several transactions in which Boesky had used information obtained from Levine; his profits on these deals were estimated at $50 million. Given the previous track record of the Securities and Exchange Commission, Boesky could well have thought that his illegal insider trading was likely to go undetected and unprosecuted. So it was reasonable enough for Boesky to believe that the use of inside information would bring him a lot of money with little chance of exposure. Does that mean that it was a wise

thing for him to do?.. In choosing to enrich himself further, in a manner that he could not justify ethically, Boesky was making a choice between fundamentally different ways of living. I shall call this type of choice an ‘ultimate choice’. When ethics and self-interest seem to be in conflict, we face an ultimate choice. How are we to choose? (Singer, 1993).

The author of the above extract almost takes it for granted that insider trading is unethical. However, it is useful to ponder why insider trading is thought to be unethical and what, in particular about it is unethical.

First, consider who is harmed by insider trading?

A convincing argument can be put that insider trading does not harm the other person to the transaction. After all, that other person was a willing buyer/seller at the relevant market price. Arguably, the insider’s profit is not made at the expense of the other person. This is especially so in an anonymous market transaction where the matching of buyers and sellers is fortuitous. If the other person had not dealt with the insider at the relevant market price, he/she presumably would have dealt with another person.

Consider, then, whether insider trading harms the company to which the information relates. Although there is little empirical evidence to go on, it could be argued that investors may be reluctant to invest in a company if its securities are subject to insider trading, especially if the insider trading is done by persons connected with the company.

In such a case, the reputation of the company in the securities market may well be damaged.

In considering why insider trading is unethical and, in particular, what is unethical about it, it is useful to distinguish between insider trading by persons who are directly/indirectly connected with the corporate issuer of securities on the one hand, and insider trading by unassociated persons on the other.

In the former case, it is well recognised that persons who are directly connected with the company (such as directors/senior executives) have a fiduciary duty to act in the best interests of the company and not to exploit, for personal gain, opportunities obtained as a result of their connection with the company. Thus, to exploit inside information

coming into their possession would be to betray their fiduciary duty to the company by acting unethically and, indeed, illegally.

By parity of reasoning, it could also be argued that persons coming into possession of inside information by reason of their relationship with a person directly connected with the company (i.e. tippees or persons procured to trade by a person directly connected with the company) are a party to the betrayal of fiduciary duty or relationship of confidence, and for them to trade while in possession of inside information obtained in

that way is similarly unethical.

Boesky’s conduct was unethical because he was exploiting inside information obtained by Levine, by virtue of a relationship of confidence between Drexel (of which Levine was a principal) and Drexel’s clients. When he did so, Boesky knew that the inside information had been given to Levine in confidence by Drexel’s clients. Boesky was therefore a party to a betrayal of a relationship of confidence. Arguably, it was that Which made Boesky’s conduct unethical, and not merely the exploitation of an

informational advantage.

The position is much more difficult to analyse from an ethical point of view where the insider trader has come into possession of inside information quite independently of the company (e.g. by innocently overhearing a confidential discussion in a restaurant). In such a case, can it be said that the exploitation by that person of an informational advantage is in itself unethical? There is likely to be a division of opinion on this question.

Yet, as we will see below, the current insider trading laws of Australia provide that it is illegal (and not merely unethical) for a person in a position of special informational advantage (i.e. in possession of non-public price-sensitive information) to deal in securities of the company to which the inside information relates.

As will be seen, the policy rationale underlying the current insider trading laws of Australia, is that insider trading diminishes public confidence in the integrity of the securities market and therefore, regulation is required in order to promote investor confidence.

However, one must ask why insider trading diminishes investor confidence? Presumably, it is because investors regard insider trading as unfair. But why do they regard it as unfair? Is it because they are concerned that persons directly/indirectly connected with the corporate issuer of securities are betraying a fiduciary duty owed to the company or because they expect equal access to information in the securities market?

Underpinning the current legislation is the assumption that investors expect equal access to information in the securities market and that insider trading is unfair because it allows some persons to exploit a special informational advantage (regardless of how they obtained it).

From an ethical perspective, there must be some doubt about this assumption. Prior to the introduction of the current legislation, there were no empirical studies done to establish why (if at all) investor confidence is diminished by reason of insider trading. It could be argued (in the absence of evidence to the contrary) that investors in a securities market see discrepancies in access to information as inevitable and that the exploitation of a special informational advantage, innocently obtained, is not unethical or unfair.

It could thus be argued that the current legislation overreaches what would be an ethical solution to the problem of insider trading and, by doing so, creates criminality (as well as civil liability) in respect of conduct which, from one point of view, is not unethical.

You be the judge.

Checklist

Below is a checklist of the main points covered by this topic. Use this checklist to test your learning.

(a) Disclosure-based regulation (DBR) is integral to the Securities Commission Malaysia’s (SC) aim to ensure that the Malaysian capital market is transparent, efficient, sound and credible, and that the conduct of market participants is responsible.

(b) The role of the SC is to focus on the disclosures made and the quality of the disclosures to ensure that they are full, timely and accurate.

(c) Corporate governance is the process and structure whereby the business and affairs of a firm should be directed and managed, as well as the observance of codes of best practice and standards. One of the aims of regulation is to ensure that markets are fair. By fairness, we mean that market participants are able to compete on a level playing field, i.e. no one group of individuals or corporations is advantaged at the expense of another, and there are equal trading opportunities for everyone.

(d) The capital adequacy requirements refine the prudential benchmark for maintaining better market integrity at the level of the exchange and the clearing house.

(e) The rules of the exchanges set parameters designed to achieve greater clarity, transparency and consistency in the conduct of business of firms. The expression “fairness” is sometimes also taken to encompass the notion of investor protection (such as the elimination of fraud and manipulation, and the protection of uninformed investors against exploitation by insiders).

(f) Licensing ensures an adequate level of investor protection, including the provision of sufficient safeguards to protect investors from default by market intermediaries or problems arising from the insolvency of such intermediaries. More importantly, it instils confidence among investors that the firms and people they deal with will treat them fairly and are efficient, honest and financially sound.

(g) All licensing applications, except for applications for a new Capital Markets Services Licence, are to be made online to the SC via the Electronic Licensing Application (ELA) system.