Public sectors include the public goods and governmental services such as the military, law enforcement, infrastructure, public transit, public education, along with health care and those working for the government itself, such as elected officials…

The challenges facing governments are becoming increasingly more complex due to technological and cultural changes, demographic shifts, and the ever faster movement of money, goods and people. Governments globally are also encountering greater fiscal constraints, economic uncertainties, declining effectiveness of standard practices and procedures, as well as difficulties in attracting and retaining top talent…

Governments and businesses must accelerate their digital adoption in order to stay competitive. This will require identifying the right areas for digitalisation, prioritising technological solutions, and enhancing data privacy and cyber-security policies…

Fiscal policy is the use of government spending and taxation to influence the economy. Governments typically use fiscal policy to promote strong and sustainable growth and reduce poverty. The role and objectives of fiscal policy gained prominence during the recent global economic crisis, when governments stepped in to support financial systems, jump-start growth, and mitigate the impact of the crisis on vulnerable groups…

Overview

In Malaysia, the public sector plays a crucial role in its contribution to the GDP and provides a roadmap towards economic development, industrialization, financial planning and performance.

In Malaysia, the public sector refers to the government sector. The Malaysian public sector is divided into three levels, namely, the federal, state, and local governments. The federal government establishes various ministries, departments, and agencies (statutory bodies) in performing its duties.

In this part, basic economic theories on public finance are introduced and Malaysia’s experience in fiscal policy development is examined.

Objectives

– Discuss the role of the public sector in the economy.

– Examine the rationale for the need of a government sector in the economy.

– Examine the public sector in the Malaysian economy, and

– Describe the workings of fiscal policy and its impact on the economy.

The role of government in the economy

In order to ensure and support economic freedom as well as political freedom, the founders of our nation envisioned a very limited role for the government in economic affairs. In a market economy, such as the one established by our Constitution, most economic decisions are made by individual buyers and sellers, not by the government.

Economists, however, identify six major functions of governments in market economies. Governments provide the legal and social framework, maintain competition, provide public goods and services, redistribute income, correct for externalities, and stabilize the economy.

Citizens, interest groups, and political leaders disagree about how large a scope of activities the government should perform within each of these functions. Over time, as our society and economy have changed, government activities within each of these functions have expanded.

The public sector is that part of the economy that is owned or run by the government it exists mainly because some services such as defense, social security services, roads, water, education etc. cannot be adequately provided by the private sector.

Economic rationale for the government

(i) Defining and enforcing property rights

– Formulation of rules by the Parliament for market to operate efficiently.

– Enforcement of the rules (statutory bodies and police department); and

– Arbitrate if any conflict or dispute arises (judicial body)

(ii) Market failures (allocation function)

– Failure of competition because of existence of monopolistic powers and imperfect information.

– Misallocation of public goods for example, provision of utilities by the private sector)

– Existence of externalities (factors) not included in GNP but which have an impact on human welfare, for example, pollution); and

– incomplete markets.

(iii) Unemployment, inflation (internal balance) and balance of payments disequilibrium (external balance) i.e. stabilization functions.

(iv) Redistribution of income i.e. distribution functions.

(v) Provision of public goods, which are goods and services provided for the benefit of the population (such as education, health, housing, etc.)

The public sector in Malaysia

There are three tiers of government in Malaysia federal, state and local. The role of the federal government is considered to be the most important because it controls the bulk of tax revenues and is responsible for the conduct of macroeconomic policy.

The federal government has four main areas of economic responsibility:

– Provision of services

The responsibility for the security of the community (defence), the provision of judicial services (courts and judges in the federal sphere, e.g. the High Court); and the provision of social security and welfare services for those in need (e.g. social welfare benefits).

– National development

The provision of infrastructure, such as ports, which adds to Malaysia’s ability to produce and export goods.

– Trade regulation

Decision on competition in the private sector, i.e. whether there is adequate competition in an industry or whether some Malaysia industries should have some protection from cheaper imports (tariff policy).

– Overall economic policy

The responsibility to encourage steady economic growth with low inflation, while avoiding balance of payments disequilibrium and high unemployment.

The federal government aims to achieve the following four basic economic objectives:

– maintain levels of sustainable economic growth;

– achieve low inflation rates;

– improve the nation’s external position; and

– provide a conductive environment for private sector activities.

Fiscal Policy

Fiscal policy sets out a framework for national expenditure and income. It plays a vital role in economic growth. For example, if the government increases its spending on the country’s infrastructure like roads, it may stimulate job creation, which ultimately leads to more economic activity and growth. Fiscal policy is a process by which the national government decides on the timing and composition of government spending and taxation. It is often the case that most governments will spend money and raise taxes in order to finance their expenditure. Fiscal policy is the process through which these financial activities are achieved. The principal objectives of fiscal policy in a developing economy are; To mobilize resources for economic growth, especially for the public sector. To promote economic growth in the private sector by providing incentives to save and invest. To restrain inflationary forces in the economic in order to ensure price stability. To ensure equitable distribution of income and wealth so that fruits of economic growth are fairly dist.

Fiscal policy comprises the following instruments – changes in tax rates, transfer payments or government purchases – that the government undertakes for the specific purpose of charging the levels of output, employment and prices. The fact that the government spends more than it collects from taxes does not necessarily imply a deliberate effort to influence output and income. The purpose of fiscal policy is to reduce fluctuations in the levels of output, employment and prices and to push the economy in the direction of steady and sustainable growth of output.

In order to stabilise economic fluctuation, the fiscal policy implemented is counter-cyclical in order words, when there is recession, the stance of fiscal policy is expansionary i.e. expenditure exceeds revenue. On the other hand, when there is a boom, the stance will be contractionary. This is so, even if government expenditure does not change, as revenue collection is procyclical i.e. rising in boom years and failing in recession.

Government purchases and aggregate demand

Government purchases increase aggregate demand directly. Additional government spending increases the incomes of consumers, who will then increase their consumption spending. Hence, actual increase in real output will be larger than just the increase in government spending alone. The multiplier effect explains why the amount of increase in government spending needed to reach the target level of income and output is smaller than the gap between actual output and the full employment level of output.

Taxes transfer payments and aggregate demand

Taxes are leakages from the circular flow, leading to a reduction in planned spending. Households and corporates pay taxes. A change in taxes will shift aggregate demand indirectly. Since taxes reduce the disposable income of households and corporate income, households and corporates will respond to changes in available income by adjusting their consumptions and savings. In general:

– an increase in taxes will reduce consumption spending and therefore, reduce aggregate demand and the level of national income, and

– a reduction on taxes will increase consumption spending and therefore, increase aggregate demand, raising the level of rational income.

Transfers by the government such as welfare, scholarships, veterans’ benefits and social security, for which no production is expected in return is called transfer payments. These transfers directly affect the disposable income of households, which react by changing their consumption and savings.

The nature of the stabilization problem tends to differ between developed and developing countries. In a developed economy with a wide industrial base, substantial scope may exist for counteracting a fall in one component of demand, for example, private investment, through fiscal expansion.

On the other hand, developing countries are usually dependent on a relatively limited range of products, with the agricultural or mining sectors often responsible for a large share of output. Also, in such economies, instability often originates from fluctuations in supply, due for example, to changing weather conditions or variation in demand conditions for major export crops. In these circumstances, the traditional role of fiscal policy in stabilizing fluctuations in domestic income has to be balanced against any limitation in the responsiveness of supply and any constant imposed by the balance of payments and the external reserve position. Fiscal policy is normally not effective in a small open economy with a flexible exchange rate.

Problems in fiscal policy

Fiscal policy, in practice, is a difficult and challenging task. The process of devising and implementing a policy is slow. In addition, the choice of tools used will have important implication on the size of government expenditure, the size of national budget and income distribution.

A major problem with fiscal policy is that there can be delays between the time that a need for action is perceived and the time the policy is enacted and implemented. For example, by the time the policy is actually in place, it may no longer be appropriate. In this circumstance, the fiscal policy may destabilise rather than stabilize the economy.

The three kinds of time lags in fiscal policy are as follows:

– recognition lag – the lag in discovering the existence and size of the economic problem;

– implementation lag – the lag between recognizing the problem and legislating a policy change to address the problem. This action by the Parliament, which can be very slow;

-impact lag – the lag between changes in spending and taxes and the actual effects on economic activities.

Government finance concept

Concept of the overall balance

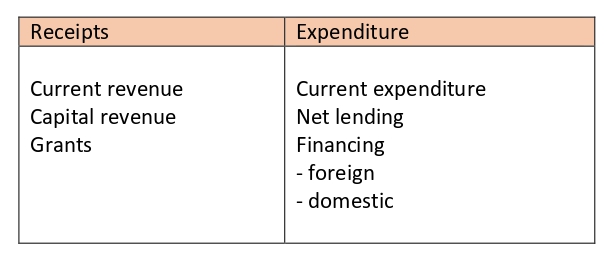

Table 1: Summary of government finances

An overall surplus or deficit is defined as total revenue plus grants (A+B+C) less total expenditure plus net lending (D+E+F). in as much as government taxes and other revenue absorb the purchasing power of the private sector and government expansionary fiscal stance. Similarly, an overall surplus may indicate a contractionary impact. However, such interpretation would need to be carefully qualified by an analysis of financing, the structure of receipts and expenditure and the factors that might be causing the deficit.

Government current account balance

The current account balance is defined as the difference between current revenue and current expenditure, excluding grants. The current account balance can be used as a measure of government savings. A high level of government savings interpreted as representing a contribution to the financing of development in as much as it allows a substantial amount of capital expenditure to be financed.

Limitations of the overall balance

A problem in using the budget balance as an indicator of policy stance is that it not only reflects the impact of the fiscal actions on the economy, but also the effects of the economy on the budget. Changes on government receipts and expenditures are due to discretionary policy actions and changes in the level of economic activity. Receipts from income tax could, for example, rise as a result of a discretionary increase in tax rates or automatically due to an increase in the level of activity and incomes.

If it is assumed that most expenditures are discretionary, while major parts of revenue vary with the level of activity, then a simple relationship between the deficit and income can be developed. In particular, as income rises, revenues will increase faster than expenditure, allowing a rising surplus or falling deficit. In this circumstance, however, a change in the deficit need not indicate any change in policy. Further changes in the overall deficit may not be an indication of the required fiscal policy action. For instance, as a result of the decline in income, a budget deficit emerges. This deficit, however, does not mean that the budget has become more expansionary due to a discretionary fiscal policy not does it indicate a need for budgetary restraint.

Another problem with the simple overall balance is that it implicitly assumes that all types of revenues and expenditure have an equal impact on aggregate demand. Thus, as long as the overall balance is unaffected, alterations in the composition of revenue or expenditure, or equal increase in both aggregates are assumed to leave the fiscal impact unchanged. This assumption may, however, prove inappropriate. For example, an increase in government purchases of goods and services, offset by an equal rise in taxation, may well have an impact on aggregate demand. This is because the rise in government purchases of goods and services directly adds to aggregate demand, while the higher taxes only reduce demand to the extent that they result in a fall in consumption, or investment, rather than savings. Similarly, government wages and salaries will have a different impact on demand than government purchases from other countries. In the former case, there is a direct contribution to domestic demand, whereas in the latter case the demand impact is transferred abroad.

Financing

The impact of a given overall surplus or deficit on aggregate demand depends on the way the balance is financed. Financing is usually divided into external and domestic borrowing.

The interpretation of an increase in the overall deficit financed by higher external borrowing depends on the way such financing is used. External borrowing does not reduce the income or expenditure of the domestic private sector. If such foreign borrowing is tied to expenditure abroad, as is the case with most official development assistance, there will normally be no immediate impact on domestic demand. Foreign borrowing used to finance domestic expenditure will, however, have an expansionary impact on the domestic economy.

Three domestic sources of finance are as follows:

(i) Printing of money (i.e. recourse to the central bank)

Net recourse to the central bank is usually considered expansionary as the rise in credit to the government does not require any compensating reduction in credit to the private sector.

(ii) Borrowings from commercial banks

The impact of government borrowing from the commercial banks depends on the extent to which such institutions are able to finance the additional credit without reducing lending to other sectors. If the commercial banks do supply of credit, increased borrowing by the government would have to be at the expense of loans to other sectors. Alternatively, if the commercial banks had excess reserves, or the central bank, through its monetary operations make additional reserves available, there would have expansionary effect on aggregate demand and the money stock. In the latter case, it might be appropriate to consolidate all net government borrowings through the banking system if the government’s fiscal policy is expansionary.

(iii) Borrowing from non-bank private sector

The impect of non-bank borrowing on private sector demand is more ambiguous. Voluntary purchases of government securities may temporarily reduce the liquidity of the private sector but are not considered to have an adverse affect on its wealth. An increase in the government’s demand for additional financial resources may, however lead to a rise in interest rates, which could adversely affect or crowd out private sector investment. Such crowding out is, however, unlikely to occur in an environment of monetary ease when funds would be available to maintain the level of private sector demand.

In developing countries, most non-bank financing may come from captive institutions, such as provident funds, which are compelled to use the resources raised from their contributors to purchase government securities. Such purchases often take place at below market interest rates. Those providing finance to these institutions are unlikely to consider the government securities purchased under these conditions as a part of their in the market. Consequently, the reduction in private sector liquidity associated with such captive finance may have a significant may have a significant contractionary effect on aggregate demand.

Impact of fiscal policy

In general, increased government expenditure (such as giving government officers an increase in salary) or tax cuts will lead to higher disposable income. Higher consumption can be expected, thereby increasing sales for businesses. Businesses will increase their orders from factories that, in turn, will increase their output and employ more people. In this way the initial increase in government spending will be multiplied several-fold. The effect of the fiscal policy is expansionary. In a similar way, during boom times, if the government cuts its spending, the reverse occurs and fiscal policy is contractionary.

Focusing only on the budget imbalance may be a simple way to assess the impact of fiscal policy on the economy, but it is a misleading way of accessing the stance of fiscal policy. The government could move from a deficit budget in one year to a balanced budget in the next year for any one of the following reasons.

– economic activity rose faster than expected; or

– the government chose to cut its outlays or increase its revenue, i.e. make deliberate changes in fiscal policy which were contractionary.

Similarly, government could move from a surplus budget to a balanced budget by increasing outlays of reducing taxes, or letting an unexpected recession do it for them.

Because of this possible confusion, economists usually make a conceptual distinction between discretionary and non-discretionary changes in the budget position. Non-discretionary changes occur because various outlays and receipts of the budget vary, automatically with the state of the economy. Hence, the size of the budget deficit or surplus will vary over time without any conscious change in fiscal policy.

Economics and policy makers have questioned the effectiveness of discretionary fiscal changes. The general view is that an expansionary fiscal policy will have temporary effects on output and employment. The reason is that bonds will have to be issued to the general public in order to finance government outlays not financed by extra tax revenues. As such, argue the critics the government is effectively borrowing savings which would otherwise have been lent to the private sector, resulting in excess demand for funds by the private sector. Because of the greater demand for funds, interest rates will rise and private spending will be discouraged to ‘crowded out’ by the higher rates.

Thus the initial expansionary effects of increased spending or lower taxes would be whittled away over time. Empirical studies suggest that the ‘crowding out’ effect is only partial at best and that expansionary fiscal policy does have desired effect on spending and growth.

Fiscal consolidation in Malaysia is being driven by outlay restraint across the general government sector (thus sector is directly responsible for taxation and for the provision of government services such as social welfare, public hospital, schools and police). Before 1998, fiscal consolidation had substantially reduced and/or eliminated the need for new external financing to support government expenditures.

Exercise:

1. An increase in government spending shifts the aggregate demand schedule:

A. upward by the increase in government spending.

B. downward by the increase in government spending

C. upward by the increase in government spending times the expenditure multiplier

D. downward by the increase in government spending times the expenditure multiplier

2. The public debit imposes a burden on future generation if:

A. the government balance the budget over the business cycle

B. it is completely owned to the citizen of the issuing country

C. it is largely owned to foreigners

D. taxes do not have to be increased in the future to cover higher interest payments on the debt