What is the Real Economy?

The real economy refers to all real or non-financial elements of an economy. An economy can be solely described using just real variables. A barter economy is an example of an economy with no financial elements. All goods and services are purely represented in real terms. A barter economy does not require the presence of an underlying monetary system…Read more

It is also referred to our ability to produce things that people need and want such as food, clothing, shelter, societal infrastructure, machinery, computing, etc. It’s more or less a function of the amount of workers there are and how much capital (machines, technology, etc.) they can bring to bear on their work — all other things equal, the more that both of these increase, the more the economy is able to produce what it needs to sustain itself and thrive…Read more

Overview

The real economy refers to all real or non-financial elements of an economy. An economy can be solely described using just real variables. A barter economy is an example of an economy with no financial elements. All goods and services are purely represented in real terms. A barter economy does not require the presence of an underlying monetary system.

The real economy concerns the production, purchase and flow of goods and services (like oil, bread and labour) within an economy. It is contrasted with the financial economy, which concerns the aspects of the economy that deal purely in transactions of money and other financial assets, which represent ownership or claims to ownership of real sector goods and services.

In the real economy, spending is considered to be “real” as money is used to effect non-notional transactions, for example wages paid to employees to enact labour, bills paid for provision of fuel, or food purchased for consumption. The transaction includes the deliverance of something other than money or a financial asset. In this way, the real economy is focused on the activities that allow human beings to directly satisfy their needs and desires, apart from any speculative considerations. Economists became increasingly interested in the real economy (and its interaction with the financial economy) in the late 20th century as a result of increased global financialization, described by Krippner as “a pattern of accumulation in which profits accrue primarily through financial channels rather than through trade and commodity production”.

The real sector is sensitive to the effect liquidity has on asset prices like, for example, if the market is saturated and asset prices collapse. In the real sector this uncertainty can mean a slowdown in aggregate demand (and in the monetary sector, an increase in the demand for money).

The real economy of any nation reflects the aggregate demand for and aggregate supply of goods and services in the economy at constant prices. Both the aggregate demand and supply of goods and services can be summarised in the national income.

The part in traduces the basic aspects of national income and inflation and how both these factors affect the economy. The two main concerns of macroeconomics are inflationary pressure and unemployment.

Objectives

– Describe the information contained in the national income of an economy of an economy and the concept of GNP and GDP.

– Examine the methods of measuring national income and Malaysia’s national income accounting.

– Discuss the productive sectors of the economy and the importance of such sectors in the Malaysian economy.

-Discus the concept of inflation and the causes of inflation, and

– Gain an insight into Malaysia’s inflationary experience.

The national income

The total income of an economy or a nation is represented in the national income accounts. The national income accounts provide a summary measure of the values of a myriad of economic activities taking place in a country during a specified period of time.

The national income accounts provide information on the following:

(a) what and how much an economy produces;

(b) the productive sectors of the economy;

(c) the amount of savings and investments in the economy; and

(d) the distribution of income among factors of production, i.e. land, labour, capital and entrepreneur.

Some uses the national income accounts can be summarised as follows:

(a) suitable statistical framework to measure some key economic variables and to facilitate the analysis of the behaviour of an economy.

(b) means of comprising the performance of the economy against its potential performance.

(c) means of making inter-temporal comparisons in order to judge the progress of the economy through time; and

(d) means of comparing the economic well-being of different countries at a certain point in time.

Methods of measuring national income

Production is generally defined as the output of final goods and services. Production is a process by which value is added to the value of goods and services in existence. From this production data , the economy’s gross output can be calculated Gross output is the sum of all goods and services that comprise the final product. Since intermediate products are incorporated into final products, they are implicitly included in gross output. As such, care should be taken to ensure that double counting is avoided.

Example

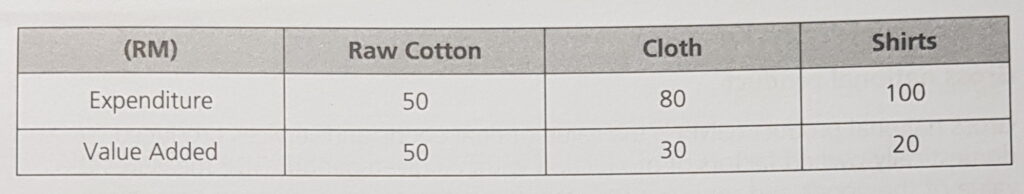

Raw cotton produced by the agricultural sector is converted into cloth by the textile industry and into shirts by the garments industry. Their transactions are summarised below:

The textile industry sells its cloth for RM80. The value that this industry adds to raw cotton is only RM30. The value of the final product (shirt: RM100) is identical to the total value added by all three transactions (RM(50 + 30 + 20) = RM100).

Based on the above example, we can measure output in three ways:

(i) The expenditure method – under which society’s expenditure on final products (RM100 for shirts) constitute gross output.

(ii) The value-added method – under which the creation or addition of value by each industry is added up (RM(50+30 + 20) = RM100)

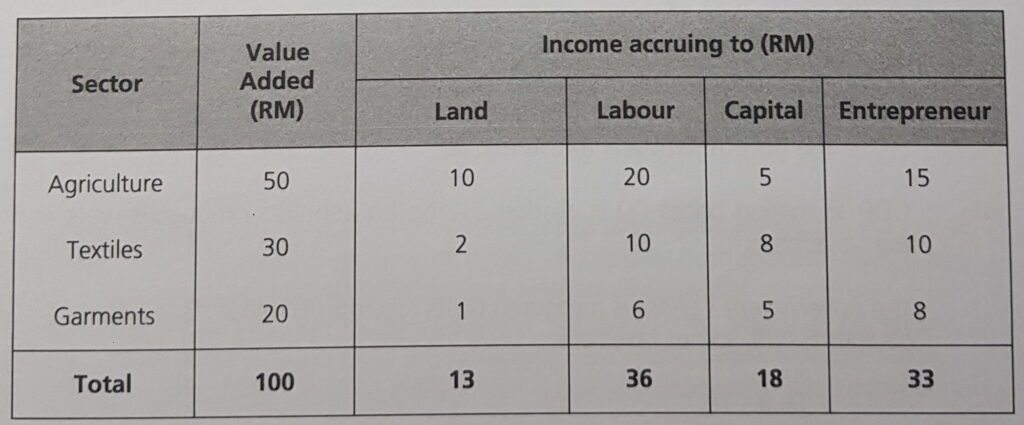

(iii) The income method – under which income accruing to each factor of production is added. The income method can be illustrated as follows:

Theoretically, all three methods of measuring gross output should give identical results. In practice, however, discrepancies may occur due to factors, such as the variety of sources for different types of data and the various agencies involved in the collection and synthesis of information. Other problems that may arise in measuring gross output include the existence of an underground economy where transactions are unrecorded under-reported and there are changes in quality of goods and services supplied.

Measurement of gross output

Gross domestic product

Gross domestic product (GDP) is the total value of current production of final goods and services within a country during a period of time, normally a quarter or a year. GDP may also be defined as the market value of the goods and services newly produced in a country and not resold during the accounting period. it is a measure of production that accrues to final users during the period. Thus, final and intermediate products must be carefully distinguished to avoid double counting.

Gross national product

Gross national product (GNP) is the value of final goods and services produced by domestically-owned factors of production within a given period. GDP measures the value of the good and services produced within the country. It is a geographical concept that takes no account of the resident status of those who supply the labour or own the capital. GNP, on the other hand, attempts to measure goods and services attributable to the labour or property owned by residents. To reconcile GDP with GNP, factor income (wages, dividends, interest, etc.,) paid to non-residents must be deducted from GDP while factor income receipts of residents earned abroad must be added to GDP to arrive at GDP.

National income identities

National income identities are useful and serve as rules for consistency checks.

(i) The value added of the economic sector must be equal to the pretax factor income.

GDP = W + QS + Ts

W = wages and other remuneration of employees (household)

QS = operating surplus of producing units (firm)

Ts = sales taxes and other indirect taxes plus transfers received by the

government less transfers paid.

(ii) GDP at market price (Y) is divided among households, producing units and the government:

The government share is measured by its receipts (R) minus it transfer payments (TP), so net taxes are:

T = R – TP

The shares going to households includes after-tax income plus net transfers received (Yd).

The share of producing units includes the operating surpluses are interest and dividends paid and income taxes and other direct taxes on producing units (SB).

Y = Yd + T + SB

Y = GDP at market prices

Yd = personal disposable income

T = net taxes, or government receipts, R minus its net transfer payments,

TP.

SB = saving of producing units.

(iii) GDP at market prices must equal to the sum of consumption expenditure plus gross investment expenditure plus net exports.

Y = TC + Tlg + NX Where, Y = C + I + G + X – M

Y = GDP at market price

TC = total consumption expenditure

Tlg = total gross investment in plant and equipment plus the change

NX = net export, export minus import

C = private consumption expenditure

I = gross investment in plant, equipment and inventories

G = government purchases of goods and services

X = exports of goods and non-factor services

M = imports of goods and non-factor services

Malaysia’s national income

Since Malaysia achieved independence in 1957, its economy has registered a consistently high growth rate. Malaysia’s GDP grew steadily from an average from an average annual rate of 4.1% in the second half of the 1950s to 8.1% in the 1970s. The early 1980s witnessed a slowdown in economic growth due to the prolonged world recession and the existence of structural problems in the domestic economy. This culminated with a recession in 1985, when real GDP contracted by 1.1%. In the early and mid-1990s, Malaysia experienced several years of rapid economic growth, with the GDP growth at an average of 8.5% between 1991 and 1997. However, the 1997/1998 Asian Financial Crisis disrupted this growth momentum, resulting in negative growth rate of 7.4% in 1998. Despite the slowdown in 1998, it quickly regained its growth during 1999 and 2000 with an average GDP of 7.2%. In the last decade, the Malaysian economy continued to expand at an average rate of 4.6% per annum.

Over the last 50 years, the Malaysian economy has undergone significant structural changes. The economy expanded from a two-commodity economy namely, tin and rubber to a more broad-based and resilient economy with a well-diversified production based and a wide range of exports, namely rubber, tin, palm oil, timber, cocoa, crude oil and increasingly, manufacturers. Like many developing countries, Malaysia is highly dependent on exports and is open to changes in the international trade environment. Nevertheless, the economy has managed to achieved high rates of growth with relative price stability.

The economy of Malaysia is expected to continue its growth at a satisfactory rate in the future. Nevertheless, the management of the economy will be more challenging than before. efforts to sustain competitiveness will be intensified in light of competition for trade and investment with countries like Indonesia, Thailand, China and Vietnam. Malaysia will also need to expand the range and quality of its products as well as exploit new export markets. These efforts will be pursued as Malaysia’s drive towards becoming a fully developed economy by the year 2020.

The productive sectors

The productive sectors of the economy represent the aggregate supply side. Malaysia is essentially a trade-oriented economy based initially on agriculture, but increasingly on industry in 1957, when independence was attained, agriculture accounted for about 40% of GDP and over 60% of total employment and export earnings. However, following the implementation of policy measures in the 196-0s and 1970s aimed at export diversification in the agriculture, mining and manufacturing sectors, the economy has become fairly well diversified and services and manufacturing sectors have become the main contributing sectors.

Aggregate demand

Aggregate demand comprises the following:

– private final consumption expenditure, which comprises expenditure on goods and services by households (other than capital goods; which are treated separately);

– private gross fixed capital expenditure, which comprises private expenditure on capital;

– public expenditure, which comprises government consumption and public fixed capital expenditure;

– increase in stocks, which the change in stocks of goods for sale, raw materials and work in progress and fuels held by private enterprises and public marketing authorities; and

– exports and import of goods and services, which comprise the expenditure by foreign residents Malaysia-produced goods and services and expenditure by Malaysians on foreign-produced goods and services respectively.

Inflation

Inflation occurs when there is an increase in the general price level (i.e. when the cost of a given quantity of goods and services increases). Inflation reduces the purchasing power of a unit of money and occurs when a given quantity of money purchases a smaller quantity of goods and services. Inflation is also defined as a persistent tendency for the general price level to rise.

Indicators used to denote inflation are as follows:

– consumer price index;

-producer/wholesale price index:

– GDP deflator;

– export and import price index;

– retail price index (United Kingdom);

– domestic supply price index (Singapore)

The consumer price index (CP) is the most popular indicator used to measure inflation. However, it is only applicable to the consumer sector and not other sectors, such as the supplier sector. The retail price index covers the retail sector while wholesale price index is confined to the wholesale sector. Only the GDP deflator covers the whole economy. Export and import price indices are used to measure the terms of trade and price competitiveness vis-a-vis other services. Singapore uses the domestic supply price index to measure domestic cost inflation.

The CPI is the most popular inflation indicator used in Malaysia. It measures the average rate of change in prices of a fixed basket of goods and services which represents the expenditure pattern of all households in Malaysia. It is a composite index, weighted by regional expenditure weights based on three regional indices computed separately for Peninsular Malaysia, Sabah and Sarawak. The base year expenditure weights for the three regions were derived from the household expenditure survey.

Domestic factors contributing to inflation

Demand sources of inflation

Inflation can be generated by excess demand, i.e. the level of aggregate demand for goods and services in excess of the flow of goods and services produced. Based on the principles of supply and demand., a temporary disequilibrium resulting from an increase in demand may lead to a higher profit margin and a subsequent increase in supply. However, persistent excess in demand over supply implies that the monetary value of demand exceeds that of output at current prices. Under such circumstances, price will tend to rise to reconcile the difference unless direct controls are imposed upon them.

Money supply and inflation

Excessive monetary expansion is considered one of the basic mechanisms through which excess demand for goods and services are generated. An increase in monetary expansion in excess of growth in real output will lead to an increase in the amount of real cash balances that are in excess of what individuals and firms desire to hold. They will, therefore, exchange their excess cash balances for other financial asset as well as for goods and services. Thus, aggregate demand will increase. If production cannot adjust sufficiently or if it is at the full employment level, prices will tend to increase. Price will continue to rise until excess real cash balances are eliminated.

The rate of increase in domestic inflation will depend on the rate of expansion of money supply and the extent of the flow excess cash balances abroad. A country may witness a shift of expenditure patterns away from domestically produced goods towards imports. This process will be constrained by the availability of foreign reserves in the economy. If foreign reserves are not sufficiently available, domestic prices may take most of the brunt of excessive monetary expansion in the economy.

Government expenditure and budget deficit

Government expenditure has a direct and significant influence on the level and composition of aggregate demand as well as on inflation. The manner in which budget deficits are financed also has an impact on inflation.

Most of the cases of chronic and hyper-inflation, as well as a great majority of cases of mild inflation, have their roots in fiscal deficits that are financed by recourse to the banking system. Inflation is almost inevitable when fiscal deficit financing allows money to be created at too fast a rate in relation to the real growth of the economy. Inflation may be generated even if budget deficits are financed through borrowing from capital markets (rather than banks). Generally, recourse to the non-bank sector, such as purchases of government securities by the non-bank public (which amounts to a redistribution of domestic savings), has less inflationary impact than allowing the money supply to increase.

Fiscal policy can influence inflation directly through the prices in the sectors to which spending is channel. Government spending could cause a shift in sectoral demand. As a result, excess demand may appear in some sectors while some other sectors of the economy may experience excess capacity. Prices and wages are likely to rise in sectors experiencing excess demand. Further, immobility of resources from the excess capacity sectors to the excess demand sectors may present a dampening of the inflationary effect that arises out of the sectoral shift in demand.

In this regard, prices and wages in the excess capacity sectors which may not fail due to downward inflexibility and the immobility of resources, may even increase for several reasons. First, wages in the excess capacity sectors may be linked to those in the excess demand sectors. Second, the excess capacity sectors may use as inputs the higher priced output of the excess demand sectors. Third, the increase in the general price level, which resulted from the price increase in the excess demand sectors, may generate a rise in wages and prices throughout the whole economy if nominal wages are automatically adjusted to a cost of living index.

It is important to recognize the independence between budget deficits and inflation. In some industrial countries, government receipts tend to rise more rapidly than government spending as a result of a short-term increase in the rate of inflation. In most developing countries, however, government expenditure rises concomitantly with inflation while government revenue tends to fall behind due to collection lags. The financing of this inflation-induced deficit would then increase money supply and generate further inflation.

Private expenditure

Inflation could result from excessive expenditure. Increase I private expenditure may be due to the excessive extension of back credit to the private sector. Inflation increases when credit expansion to the private sector is not under the firm control of monetary authorities. While the general perception is that credit the productive purposes is not inflationary, excessive extension of credit to the private sector would lead to an excess supply of money balances and an excess demand for goods and services, which would then have an inflationary impact.

Supply factors contributing to inflation

Wages and productivity

Money wages may rise in response to the pressure of excess demand in the labour market. When the level of output is rising, firms tend to increase employment and money wages are likely to rise. The initiate may also come from the labour’s side in the form of wage demands. Increases in money wage rates, if not offset by productivity gains, will increase labour costs and this will eventually lead to an increase in product prices.

Wages increases are probably one of the most significant sources of cost-push inflation. This is so because in modern economies, governments have actively pursued full employment policies. Furthermore, an increasingly organized and defiant labour force and the acquiescence of firms operating in rapidly growing markets have exacerbated the problem of wage inflation.

The growth of both economic and political power by group of workers and the readily available information on the earning in other sectors of the economy and even in other countries have made wage inflation easily transmittable. Thus, a wage increase in one profession becomes a signal foe wage increases in complementary professions of the economy.

Market structure

It is possible for business monopolies to mark up prices relative to costs if they believe that the market demand for that products has changed sufficiently to allow such a practice. If many industries increase their profit margins, the economy will experience a profit inflation. This tends to accentuate inflation originated from the demand side. Sellers are naturally ready to exploit any opportunity which presents itself for raising prices. Such opportunities tend to increase the demand for their products. Although such cost-push pressures are sectoral in nature and originate from the monopoly sector, they are likely to filter through to other sectors of the economy.

Monopoly power becomes more serious when it exists in both business and labour. The combination of both could create a built-in inflation that could gear the economy to a condition of ever increasing prices.

Excess demand may also induce cost-push pressures in general through the process of expansion of output. Due to scarcity of some inputs such as materials and managerial talent, economic expansion is likely to increase cost not only because of diminishing returns but also because successive units of input, be it labour of capital, are not equally efficient. Expansion of production often involves the hiring of less skilled workers and the utilization of older equipment and therefore, adds to diminishing returns. This occurs in the production of both manufactured and agricultural goods. However, in the long run, improvements in technology and training can offset such possible cost increases.

Skill workers and the utilization of older equipment and therefore, adds to diminishing returns. This occurs in the production of both manufactured and agricultural goods. However, in the long run, improvements in technology and training can offset such possible cost increases.

Structural constrains

Inflation is inevitable in an economy facing structural bottlenecks or constraints and attempting to achieve rapid growth. Three basic structural constraints have been identified, namely supply inelasticity, foreign exchange bottlenecks and financial constraints.

– Supply inelasticity

The most important form of supply inelasticity in developing countries lies in agriculture. The weak supply response of the agricultural sector is due to structural constrains pertaining, among other things, to land ownership and market integration. Demand for food is likely to rise in an economy that is experiencing growth and if food supply fails to increase to match the increase in demand then food prices will rise. Agricultural prices tend to be more sensitive and to respond more quickly to changes in demand than prices of manufactured goods. Inflation in the agricultural sector is likely to have repercussion in other sectors of the economy.

Inelastic goods supply may not be the only bottleneck impacting growth and contributing to inflation. For instance, economic growth produces expansion in demand for public utilities such as power and transportation. Response of supply to prices in these sectors is also very slow

– Foreign exchange bottlenecks

For many developing countries, the growth in foreign exchange receipts is not sufficient to meet the growth in the demand for imports generated by development efforts. Many developing countries find it difficult to expand their export earning because demand for their exports, which are predominantly primary products, have low-income elasticity and the markets for such products are competitive. Unavailability of sufficient foreign exchange to provide the economy with necessary imports has an inflationary impact as shortages in materials, intermediate goods and capital equipment for the manufacturing and other sectors would curtail domestic production.

Policies aimed at solving foreign exchange bottlenecks may not necessarily mitigate their inflationary impact. For example, by raising tariffs on imports, prices of goods to domestic consumers will be forced up. On the other hand, a policy of import substitution, without sufficient regard to comparative costs can also be a source of inflationary pressures. Furthermore, pursuing an import substitution policy will introduce inflexibility into the production structure. This will increase the likelihood of inflation being imported through rising the impact of shortages of foreign exchange more significant on inflation. Import substitution policies should be designed to encourage industries to achieve a more efficient scale to eliminate inflationary pressures. However, monopolies operating in a protected market do not have the incentive to be cost-conscious.

– Financial constraints

Industrialization increases the need for government physical and social infrastructural facilities, which necessities increases in government expenditure. However, government revenues in many developing countries expand less rapidly than their expenditure needs. This could be due to an inefficient tax collection system and inadequate tax structure. The problem is usually circumvented by recourse to deficit financing leading to inflationary consequences.

The inadequate financial markets that prevail in many developing countries compound the inflationary impact of government deficits. This is especially true when a large portion of the deficit has to be financed through borrowings from the banking system. Inadequate financial markets also hinder mobilization of savings and limit private capital formation. As a result, governments tend to assume a larger role in capital formation.

The above structural constraints become insidious in an economy that is attempting to achieve rapid growth. Such constraints exist in most of the developing countries through inflationary and non-inflationary periods. In many cases, these constrains have resulted from policy measures. For instance, in appropriate pricing policies including interest rates and exchange rates have introduced distortions to the market mechanisms in many countries. Attempts to achieve rapid growth normally create demand pressure accompanied by excessive growth in credit and money supply. Bottlenecks then aggravate inflationary pressures.

External factors contributing to inflation

Small open economy under a fixed exchange rate system

Small and open economy to the rest of the world varies from country to country. A tight linkage applies when internationally traded goods and services contribute a large proportion of the total goods and services contribute a large proportion of the total goods and services of the economy. A loose linkage applies when the share of internationally traded goods and services in the economy is small. The latter may result from trade and payments restrictions.

If inflation prevails in the rest of the world and assuming that the rate of inflation in the country remains initially unchanged, this will induce an increase in foreign demand for the country’s goods and services resulting in an improvement in its balance of payments. An excess demand for the country’s currency will emerge in the foreign exchange market. To prevent an appreciation of its own currency under a fixed exchange rate system, the country’s monetary authorities will have to purchase the excess supply of foreign currencies with their own currency. This will cause the domestic supply of money in the country to increase, thus causing the rate of inflation to adjust towards the world level. The adjustment will involve both traded and non-traded goods and services. The adjustment in prices of non-traded goods and services will also be aided by the shift in expenditure by public of the country away from internationally traded goods and services towards domestic goods and services. This shift will be induced by the initial disequilibrium in relative prices between traded and non-traded goods and services.

In short, under a fixed exchanged rate system, countries experiencing surpluses in their balance of payments will import inflation while deficit countries will export inflation. The extent to which inflation is transmitted from abroad will be larger for a tightly linked than a loosely linked economy.

The above analysis may not apply to countries with a limited export potential and inelastic demand for imports. Under such circumstances, a country may not experience importation of foreign money. On the contrary, it is more likely to experience deterioration in its balance of payments and a reduction in foreign reserves and consequently a reduction in money supply. In this case, world inflation will be transmitted directly through the increase in import prices. Prices of non-traded goods and services will be affected in two ways. First, the shift in domestic demand towards non-traded goods and services will induce a price increase. Secondly, the reduction in money supply due to the deterioration in the balance of payments will have a dampening effect. The magnitude of each effect will determine the end result.

Small open economy under a flexible exchange rate system

When foreign demand for a country’s goods and services increases, this will result in an increase in the demand for the country’s currency in the foreign exchange market. Monetary authorities are not under the obligation to accumulate foreign exchange to stabilize the exchange rate and, hence, domestic money supply may not increase. In this situation, the exchange rate will appreciate, inducing and adjustment in relative prices of traded goods towards equilibrium and a slowdown, if not a halt, in importation of foreign money. Furthermore, a shift in domestic expenditure from traded to non-traded goods is less likely to take place and, therefore, an increase in prices of non-traded goods will not materialize. In addition, as a result of the appreciation of the domestic prices of traded goods will not increase. Thus, a floating exchange rate system would prevent the transmission of excess demand from one country to another.

Impact of the real economy on the capital market

The national income

National income indicators are important to the capital market. An improvement in the national income reflects the betterment in the economic well-being of the economy, which will enable the economy to support further development and activities in the capital market. Release of the national accounts, which provide details about economic growth, may also impact investment values stronger than expected growth implies greater prospects for company earnings, thereby increasing share prices. However, this may also imply rising inflationary pressures, which will result in weaker bond prices. The make-up of growth can also be important for different sectors of the market. Financial markets often reflect what goes on in an economy because the value of an investment is determined by its expected cash flows and the aggregate economic environment also influences its required rate of return.

Inflation

Inflation has a direct impact on the value of debt and equity markets. A high inflation rate may lead to a tightening of monetary policy, which in return will result in an increase in interest rates. This will lead to lower bond prices in the debt market. Higher interest rates will have a negative impact on cost of financing, which will result in deterioration in a company’s financial performance. Hence, this may lead to a fall in share price.

What is a Business Cycle?

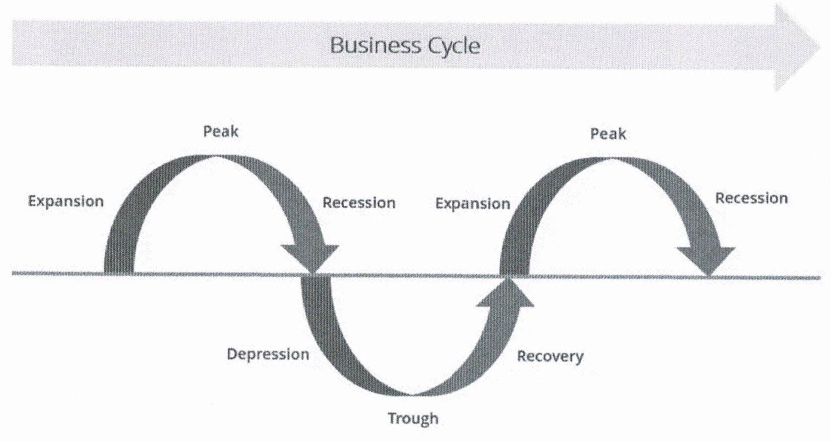

A business cycle is a cycle of fluctuations in the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) around its long-term natural growth rate. It explains the expansion and contraction in economic activity that an economy experiences over time.

A business cycle is completed when it goes through a single boom and a single contraction in sequence. The time period to complete this sequence is called the length of the business cycle.

A boom is characterized by a period of rapid economic growth, whereas a period of relatively stagnated economic growth is a recession. These are measured in terms of the growth of the real GDP, which is inflation-adjusted.

Exercise:

1. GNP is the market value of

A. all transactions in an economy during a 1-year period

B. all goods and services exchanged in an economy during a 1-year period.

C. all final goods and services exchanged in an economy during a 1-year period.

D. all final goods and services produced in an economy during a 1-year period.

2. Which of the following is NOT an indicator used to denote inflation?

A. Money supply

B. Producer/Wholesale price index

C. GDP deflator

D. Retail price index

3. Which of the following will have an adverse impact on share prices?

A. High economic growth

B. Lower interest rate due to easy monetary policy

C. High inflation

D. Higher money supply

4. In a simple cost-push model, an increase in the price of output will:

A. Increase prices and output

B. Increase prices and reduce output

C. Increase prices with no impact on output

D. have no effect

Additional Questions:

Business Cycles

Source: Corporate Finance Institute (Business Cycle)

1. Which of the following is NOT a stage in the BUSINESS CYCLE?

A. Recession

B. Recovery

C. Expansion

D. Failure

2. In the _______ stage, COMMODITIES AND STOCKS are attractive investment opportunities.

A. Recession

B. Recovery

C. Early Expansion

D. Late Expansion

3. In the _______ stage, CYCLICAL INVESTMENTS are attractive investment opportunities.

A. Recession

B. Recovery

C. Early Expansion

D. Late Expansion

3. In the _______ stage, REAL ESTATES are attractive investment opportunities.

A. Recession

B. Recovery

C. Early Expansion

D. Late Expansion

4. In the _______ stage, BONDS are attractive investment opportunities.

A. Recession

B. Recovery

C. Early Expansion

D. Late Expansion