Investment guide

Ethical and responsible investing is not a foreign concept. Globally, investors are showing interest in investments that cover a whole range of ethical options, from investing in businesses which cause the least environmental damage to those that safeguard human rights, or promote corporate governance and shareholder advocacy…Read more

The word “Compliance” means:

The act of obeying a law or rule, especially one that controls a particular industry or type of work.

Examples:

(a) Knowledge of banking and regulatory compliance is required for this post.

(b) Our cake is made in strict compliance with the original recipe.

(c) We have been working diligently to ensure compliance.

(d) In this industry, compliancy with the highest safety standards is key.

(e) We hope that the new policy will result in a higher compliancy rate.

Compliance

Contents

Overview

Introduction

Objectives

1.0 Compliance

1.1 What is Compliance?

1.2 What Compliance is Not

2.0 The Compliance System

2.1 Establishing a Compliance System

2.2 The Compliance Plan

3.0 Implementing the Compliance Plan

3.1 The Compliance Committee

3.2 Structure of the Compliance Program

3.3 Tools of Compliance

3.4 Role of a Compliance Officer

4.0 Requirement to Adopt Compliance Procedures

5.0 Authority of the Compliance Officer

6.0 Summary

Appendix 1: Case Examples of Compliance Failure

Suggested Answer

Overview

Introduction

Even before 1917, when a case before the Supreme Court referenced speculative securities schemes that had no more value than a patch of blue sky, regulatory agencies have attempted to protect investors from fraud, and provided frameworks for fair and orderly market operations.

In the 100 years since, there has been a slow but steady rise in regulatory activity across all industries—leading to the 24,694 pages of final rules published in the Federal Register in 2015. As a result, financial regulatory activity is taking up more space on corporate calendars than ever before. A total of 1,371 institutions lobbied the Dodd-Frank bill during the legislative process. And after the enactment of the “Conflict of Interest Rule” on fiduciary investment advice, the Department of Labor (DOL) received a record 3,134 comment letters from both institutions and individuals.

Agency activity around oversight of the investment industry has increased correspondingly (see figure 1). In 2016, the US Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) reported 868 enforcement actions stemming in part from examinations of 17 percent of investment companies, a record high on both counts…Read more

In this topic we look at the concept of compliance — an aspect of a fund management company’s business that has received much publicity and attention over the years. Compliance is a term that is often misunderstood and it is important that fund management company’s representatives have a proper appreciation and understanding of the term and of how compliance is a vital part of a fund management company’s business.

Objectives

At the end of this topic you should be able to:

(a) define ‘compliance and ‘due diligence’ and suggest the circumstances in which each is appropriate

(b) appreciate the significance of the compliance function to a funds management company

(c) recognise that compliance is your responsibility

(d) list the key steps in establishing a compliance system and the tools that can be used to build one

(e) describe the role of a compliance officer

Why Investment Compliance?

Regulatory rules are becoming more complex and paramount for investment managers dairy, by day but the need of compliance will help portfolio managers not only to fortify their presence in market but to effectively manage their portfolio. Investment compliance can be defined in many ways as per the prevalent rules in the industry, in general the compliance within the asset management industry or investment banking adhering to the regulatory guidelines to trade in the market and by following both internal standards set by internal management and external compliance set forth by legal or regulatory authorities…Read more

Risk, Regulation and Compliance

Redefining the value of regulation for Fund Management Companies.

A corporation that conduct business in the regulated activity of fund management in Singapore are required to either hold a capital

markets services licence issued by the Monetary Authority of Singapore (“MAS”) as a Licensed Fund Management Company (“LFMC”) or Venture Capital Fund Manager (“VCFM”), or be registered under paragraph 5(1)(i) of the Second Schedule to the Securities and Futures (Licensing and Conduct of

Business) Regulations as a Registered Fund Management Company (“RFMC”) (collectively known as “FMCs”)…Read more

1.0 Compliance

1.1 What is Compliance?

The age of compliance has arrived — and will not go away!

We have seen in previous topics that the law in Malaysia may impose severe personal liabilities on the directors and officers of a fund management company where that company breaches the law. Those penalties may include both financial penalties and imprisonment.

We have also seen that a potential defence to a breach of the law (and therefore relief from the penalties) may exist where the directors and officers can demonstrate that they have properly completed a procedure known as ‘due diligence’ in relation to an activity which is subsequently found to be in breach of the law.

But what is ‘due diligence’? How can directors and officers demonstrate that it has been properly completed? And how is it different to ‘compliance’?

Compliance is a management discipline to ensure that an organisation, such as a fund manager, actually complies with the laws, regulations and codes of practice relating to its business activities.

Different terms are frequently used in discussions of ‘compliance’ –including legal compliance, due diligence, and risk management.

Legal Compliance

The term ‘legal compliance’ tends to be used to emphasise that business activities should be conducted within the law. A fund management company should therefore ensure that it complies with its legal obligations under, for example, the Capital Markets and Services Act 2007.

Due Diligence

‘Due diligence’ is a term often used in completing a legal obligation, such as ensuring that a prospectus for the issue of shares or units in a unit trust complies with the Companies Act or the Prospectus Guidelines for Collective Investment Schemes, or in reviewing the process leading to an investment recommendation. In conducting due diligence, it is common to utilise checklists as part of the review procedure. Sometimes due diligence refers to adherence to wider obligations — such as complying with corporate philosophy or ethics — in addition to compliance with legal obligations.

Risk Management

Compliance is also often associated with the term ‘risk management’ since it relates to the control or management of risks that arise from breaches of the law. The ‘compliance system’ is all the formal measures taken by management to ensure that it meets all the obligations imposed upon it by law. Sound compliance systems could therefore be considered as a type of insurance against the risk of breach of the law.

In this topic the precise technical meanings of these terms and the differences between them are not relevant. Of greater significance is that you appreciate the importance of compliance and gain an understanding of the need for a compliance system and the role of a compliance manager within that system.

1.2 What Compliance is Not

We have said that compliance is a management discipline. It is a kind of quality or ‘best practice’ management.

In a manufacturing environment, quality control is a discipline designed to achieve a reliable output of product with no (or minimal) defects at a reasonable cost. In the legal compliance area of a fund management company’s business, disciplines are to be designed and implemented with a view to achieving full compliance with its legal obligations, consistently and at a reasonable cost. The ‘output’ of a legal compliance system is proper compliance with the law and the removal of the potential (and severe) consequences of failure to comply with the law.

Compliance is often thought to be the domain of lawyers. Many involved in the compliance area in the securities industry and in a fund management company’s office may be qualified in law. While knowledge of the legal obligations imposed upon a funds management company is clearly important, it is also significant that those involved in the compliance area have the management skills to make compliance work in a practical sense. For example, many believe that compliance ‘means’ manuals and checklists. Of much greater importance to effective compliance is the realisation that good line management and operating procedures are more significant than legalistic manuals, checklists, and reliance on external monitoring by internal and external auditors, other experts, or even the Securities Commission (SC) through its surveillance programs! The best manuals and checklists do not themselves constitute an effective compliance system. If nothing else, remember that the law, regulations and other practices change and checklists can quickly become outdated or irrelevant.

Compliance must also be distinguished from ‘audit’. While an ‘audit’ of the efficacy of a compliance system is a useful tool in assessing and proving its effectiveness, the audit function (for example, of financial statements) is usually an ‘after the event’ activity. Monitoring and checking does not prevent breaches of the law.

Compliance, on the other hand, is involved in the prevention of breaches of the law.

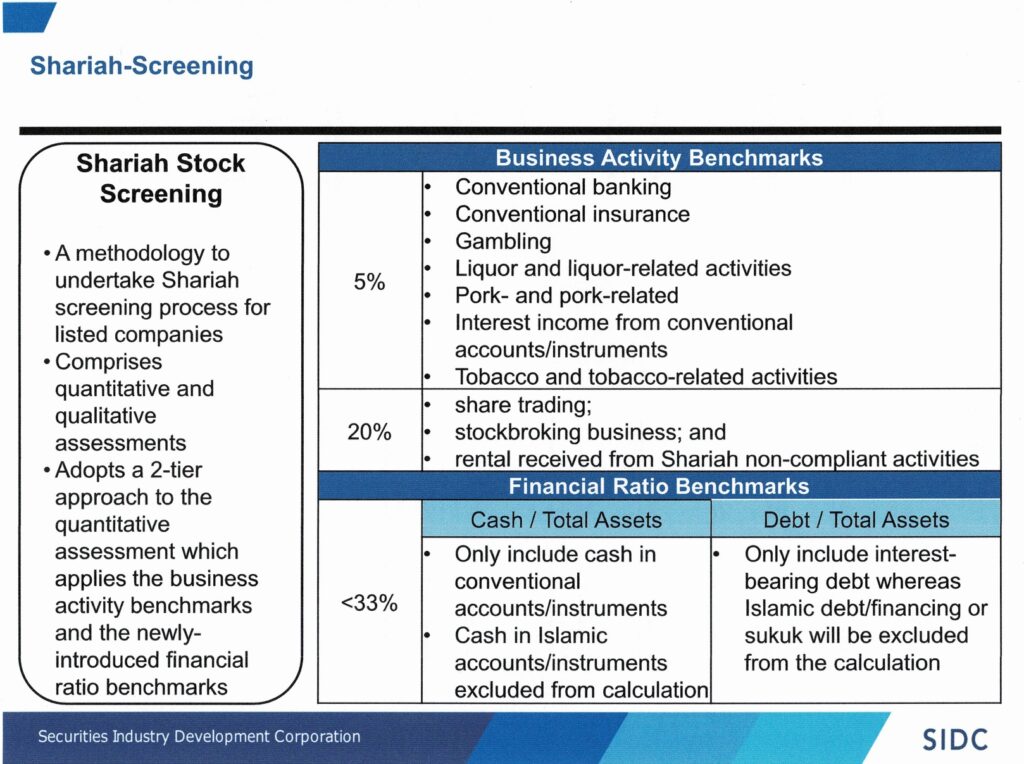

Understanding Shariah-Compliant Investments

Shariah-compliant investments adhere to the principles of Islamic law, steering clear of activities considered “haram” or forbidden, such as alcohol production or gambling. These investments provide opportunities for investors wanting to align their financial strategies with their ethical beliefs…Read more

2.0 The Compliance System

2.1 Establishing a Compliance System

With the full support of the directors, establishing a compliance system — like any important project — involves a number of steps. In a compliance system the key steps include:

(a) Establishing a proper understanding of the fund management company’s business (i.e. its management structure; products [e.g. discretionary investment management, non-discretionary management, equities, fixed interest securities, property etc.]; product design; investment processes; marketing; sales; sales and marketing culture; systems) and its existing compliance system(b) A review of the existing compliance system. (Each fund management business has an existing compliance system even if it is informal and undocumented.)

(c) Conducting a legal audit to establish the legal and other requirements (e.g. Acts, Regulations, Codes of Conduct and ethical requirements) that apply to the business of a fund management company

(d) Identification of the risks, any gaps in existing coverage of those risks, and the means by which those gaps can be narrowed and the risks realistically minimised.

(e) The production of a compliance plan and the determination of the structure of the compliance program

(f) The selection of appropriate compliance tools

(g) The implementation of the compliance program

2.2 The Compliance Plan

The compliance plan identifies all the areas of a fund management company’s business which will be a part of the compliance system (e.g. the board of directors, the board’s delegate in relation to compliance [i.e. the compliance committee], the compliance department, marketing and sales, investment, administration, IT etc.) and the aspects of compliance for which each area is responsible.

3.0 Implementing the Compliance Plan

3.1 The Compliance Committee

The Compliance Committee’s role is to direct the compliance program and to supervise its operation to ensure that it is working properly. This means reviewing the program on a regular basis to ensure that no systemic problems appear, and to ensure that appropriate disciplines are imposed when necessary.

The responsibilities of the Compliance Committee therefore generally include:

(a) setting the scope of the investigation

(b) reviewing the results of the investigation including recommendations, priorities and reporting the results to the board

(c) securing the approval of the board to the proposed compliance system

(d) approving the final form of the compliance system and allocating responsibilities and powers

(e) devising a program to properly supervise the compliance system

(f) obtaining reports on the installation of the compliance system and ensuring its installation is completed on a timely basis

(g) co-ordination of all parties involved in the compliance system

(h) reviewing reports of each compliance failure, resulting action and discipline imposed.

The disciplinary process is important since ineffective or inconsistent discipline may send the wrong signals to management and employees. All infringements should be properly considered and appropriate discipline imposed. Changes by management to eliminate the causes of compliance failures should be requested in writing, responded to (in writing) by management responsible, and properly recorded.

3.2 Structure of the Compliance Program

This aspect of the compliance system describes the structure chosen by the fund management company. The structure describes the relationships between the board, the compliance committee (where such committee has been established), the chief executive officer, the compliance officer and those involved in the various areas of the fund management company’s business identified in the compliance plan.

3.3 Tools of Compliance

Compliance tools are methods that may be used in building an effective compliance system. These will generally include:

• a board presentation on the importance of compliance to obtain the board’s commitment to the compliance plan and program, and to its implementation

• endorsement by the chief executive officer of the compliance program (evidenced by continuing emphasis on — and active involvement in — the program)

• a properly documented and detailed compliance program up-to-date manuals and checklists

• education of all directors and employees in the importance of compliance

• training of all directors and employees in compliance a system of effective monitoring of the compliance program

• identification and control of high risk areas

• a legal audit

• an effective system for complaints monitoring and resolution

• the incorporation of compliance checks into all operating procedures

• a system to report compliance system breaches

• prompt changes to the system where identified breaches occur, and appropriate disciplining of those responsible

• maintenance of detailed and complete records and statistics relating to compliance

3.4 Role of a Compliance Officer

Assuming that a compliance system has been properly planned, devised and implemented by the fund management company’s compliance officer following the principles and procedures described above, on an on-going basis, the compliance officer’s role will include:

• administering the implementation of compliance policies and procedure within the company

• updating such compliance policies and procedures and compliance manual in line with changes in the law, regulations and guidelines etc

• co-ordinating the company’s compliance efforts

• establishing procedure for the annual review of its compliance programmes

• disseminating compliance manuals, procedures and policies and any other compliance related information within the company

• establishing, maintaining and implementing policies and procedures designed to:

(a) comply with all relevant laws, regulations and guidelines etc

(b) detect and prevent violations

(c) report any material violations and/or recommend remedial action

(d) ensuring relevant personnel are appropriately licensed

(e) establish and maintain a comprehensive compliance manual

(f) report to the compliance committee (if any) and the board

It should be remembered that the role of the compliance officer is to organise and assist others in ensuring compliance occurs. It is not the function of the compliance officer to comply for the company.

4.0 Requirement to Adopt Compliance Procedures

While it is good business practice to adopt compliance procedures, there is no specific legal requirement that compliance procedures be adopted. Rather the law penalises those persons and organisations that do not comply with the law.

The SC, however, is able to, and does, consider the emphasis placed on the compliance function by an organisation — and its effectiveness — in connection with the licensing of those involved in the securities industry.

In its Guidelines on Compliance Function for Fund Management Companies, the SC requires the management company to ‘organise and control its affairs responsibly and effectively, with adequate risk management and supervisory system’.

The SC’s emphasis on compliance function has also been made apparent with the issuance of the Guidelines on Compliance Function for Fund Management Companies.

Broadly, the guidelines require fund management companies to adhere to the best practices for trading and portfolio management, reporting to clients, safeguarding of clients’ assets and specifies best practices for meeting ‘know your client’ obligations and the roles and responsibilities of the board of directors and compliance officers. In addition, the guidelines also specify the requirements for compliance with the Guidelines on Prevention of Money Laundering a Terrorism Financing for Capital Market Intermediaries.

5 Authority of the Compliance Officer

We have seen that the compliance officer has an important role to play in the business management of a fund management company. The importance of this role is evidenced by the SC’s requirement (in relation to the management of unit trust) that the appointed senior compliance officer be responsible to the board of directors.

In the past, compliance officers have been given relatively low status in the structure of many organisations in the securities industry. Low status has often meant poor support (particularly from senior management and directors) and insufficient funding to operate a compliance function in a proper manner. The result of several high-profile compliance failures (see Appendix 1) and the increasing significance placed by regulators (such as the SC) on the compliance function has been an improvement in the status of those who work in this area — and a much greater understanding of the importance of compliance and the compliance function within fund management organisations and of the need for the compliance officer to report at the highest level in an organisation.

A compliance officer’s seniority and status is crucial as reporting at too low a level will be seen by many in the organisation as having little relevance to the way they conduct their business activities. A compliance officer needs to be a strong, well-regarded individual with an appropriate level of status and authority. This is because the compliance officer will report to the senior management of the area for which the officer has responsibility. If the reports and suggestions of the compliance officer to the senior management of a business area are not taken seriously by senior management, it is highly likely that those at a lower level will treat them similarly. It would be remembered that management may have a vested interest in ignoring a compliance officer’s recommendations, for example if sales targets are likely to be affected or budgeted levels of cost exceeded. Only by reporting at a high level can these conflicts be resolved to the long-term benefit of all involved in the business area.

Resources available to the Compliance Officer

It is important too, that the compliance officer has an appropriate budget within which to work to first build a proper compliance system, and then to ensure its ongoing operation.

While the costs of a compliance function have a tendency to increase, it is usually the case that the cost of not complying increases at a faster rate!

The costs of compliance can be regarded as equivalent to an insurance premium.

The costs of not complying could extend to closure of the business by the SC, or as a result of litigation or threatened litigation by clients. Additionally, the costs of non-compliance can include financial penalties and imprisonment for those involved.

More positively, the benefits of compliance are several, including:

(a) removal of the fear of litigation and the fear of imposition of penalties (some of which are personal) for failure to comply

(b) a reduction in customer complaints and the costs of restitution (including time in ‘putting things right’)

(c) an enhancement to the company’s reputation (particularly in comparison with the consequences of failure) and the reputation of its staff — with

(d) important consequences in terms of employee morale and the ease of attracting new, high quality employees

(e) a basis for the up-dating of employee knowledge on legal and other changes in a regular and formal manner.

6.0 Summary

The purpose of this topic was to introduce the subject of compliance. It is important to appreciate that compliance is an important part of the management of the business of a fund management company. It is also important that you understand that compliance is the responsibility of everyone in your company—including you! Compliance is a requirement of doing business in the same way as keeping accounting records, meeting tax requirements and internal audit.

In the next topic we will conclude our study of the regulation of the funds management industry with a review of some topical issues relevant to fund management companies — corporate governance and investment performance presentation.

Activity 1

Refer to your copy of the CMSA 2007.

For which activity under s.212 of the CMSA is conducting ‘due diligence’ a defence?

Appendix 1:

Case Examples of Compliance Failure

The objective of describing the following major failures in compliance procedures is to increase your appreciation of the compliance function and the consequences of failure.

In the first case, the compliance failures are described by the responsible regulators after completion of their investigations. In the second case, the source is an industry commentator writing as events unfold.

Case No. 1:

Jardine Fleming Investment Management

Jardine Fleming Asset Management Ltd (JFAM), a Hong Kong-based and operated company regulated by IMRO (the UK regulator), managed institutional investments and funds delegated from other firms totalling GBP1 billion.

JFAM itself delegated fund management of GBP810 million to an associated company, Jardine Fleming Investment Management Ltd (JFIM), a Hong Kong investment management company regulated by the Securities Et Futures Commission (the Hong Kong regulator). Other IMRO-regulated investment managers also delegated fund management of GBP1.2 billion to JFIM on behalf of nine customers whose funds were invested in Asian markets.

In August 1996 the Securities and Futures Commission (SFC) announced that it had reached agreement with JFIM to make voluntary payments to compensate three accounts managed by JFIM following a five-month investigation by the SFC into practices by JFIM fund managers between 1993 and 1995.

The investigation indicated that Mr Colin Armstrong, a former senior fund manager and director of JFIM, had engaged in late allocation of deals after changes in the price of the instruments traded had occurred. Moreover, there emerged a pattern of preferential late allocation in his trading regarding Japanese exchange traded options, which as reflected in:

(a) allocations to his personal account and one particular client account of deals in respect of which there had been favourable price movement between execution and allocation.

(b) allocations to three clients of deals in respect of which there had been unfavourable price movement between execution and allocation.

JFIM subsequently agreed (without admitting liability) to make voluntary payments of HK$148.96 million to compensate the three clients.

The SFC issued a public reprimand to JFIM for breaches of the SFC Code of Conduct relating to JFIM’s inadequate and ineffective internal controls and compliance monitoring over the period under investigation. The SFC found that JFIM:

(c) failed to adopt dealing procedures whereby the fund managers intended allocation for a particular trade was rewarded prior to or at the time of placing the trade

(d) failed to ensure compliance at all times with the JF Dealing Rules requiring fund managers to record in writing their intention to trade through their personal accounts prior to or at the time of placing the trade

(e) lacked an effective audit trail to monitor compliance, and, where misconduct is suspected to have taken place, to facilitate investigation.

(e) failed to ensure that adequate resources, training and managerial support were devoted to compliance monitoring; and

(f) when it became aware of the failings in dealing procedures failed to take sufficient action to remedy the situation.

The SFC reported that JFIM had, since March 1996, banned all personal account dealings by its fund managers and had substantially improved its internal control procedures and compliance capabilities. An independent compliance review commissioned by JFIM in March 1996 did not reveal serious deficiencies in the way JFIM conducted its business at the time of the compliance review.

Mr Armstrong made payment to JFIM of the amount of substantial profits made through preferential late allocation to his personal account. The SFC revoked his registration as an investment advisor and securities dealer on the grounds of misconduct.

Mr Robert Thomas, the former Managing Director of JFIM, agreed to accept revocation of his registrations with SEC on the grounds that he, as the Chief Executive of JFIM during the period under investigation, bore ultimate responsibility for JFIM’s internal control and compliance failings.

The IMR0 investigation of JFAM (who had delegated fund management to JFIM) found that JFAM:

(a) failed to adequately monitor business delegated to JFIM

(b) failed to ensure that JFIM put in place adequate systems and procedures to ensure and demonstrate, the timely and fair allocation of customer, personal and house-account deals

(c) failed to ensure that JFIM adequately supervised and enforced its fund managers observance of JFIM’s own internal dealing procedures; and filed to ensure that JFIM had well-defined compliance procedures that would be enforced.

IMRO’s investigation established that when JFAM learnt of weaknesses in, and non-compliance with, dealing procedures at JFIM, it did not take adequate steps to remedy the failings, and to remove the potential for customer disadvantage. Alternatively, JFAM could, in IMRO’s view, have terminated the investment management arrangement with JFIM and have reallocated the investment management of the delegated funds to another fund manager, but failed to do so. When JFAM learnt about the problems, the steps it took over a two-year period were inadequate to rectify them in a timely manner.

These failings were in breach of Securities and Investment Board

principles 2 and 9.

IMRO’s investigation also found that:

(a) JFAM did not disclose that some of the total commissions charged and disclosed to its customers were retained by an associated broker. In one instance the retention of such commissions (amounting to HK$26.3 million) was prohibited by JFAM’s customer agreement. Failure to disclose retention of commissions is a breach of IMRO Rules.

(b) when JFAM became aware of the failing of JFIM in December 1993, it failed to inform IMRO that investment business had been delegated to a firm which had dealing and compliance procedures which did not meet IMRO standards. In 1994 it also suggested to IMRO that there were no significant concerns about compliance. In addition, when it subsequently lodged a Statement of Representation with IMRO in 1994, the failings were not disclosed despite JFAM being aware that the failings described above remained uncorrected. However, disclosure of some failings was made in the 1995 Statement of Representation, leading to IMRO’s investigation. Failure to disclose was a breach of Securities and Investment Board Principle 10.

IMRO noted that the failings of JFAM are of particular significance because JFAM, in essence, operated only through JFIM. JFAM and JFIM showed a common chief executive, common directors, common staff and common office space. According to IMRO, JFAM was, or should have been aware of the weaknesses in the system and the non-compliance with the dealing procedures in JFIM. JFAM, as a result of this interconnected relationship could therefore have easily taken steps to remedy JFIM’s failings more quickly than it did.

IMR0 also found that after investment managers that had delegated to JFIM were in breach of Securities and Investment Board Principles 2 and 9, had failed to disclose retention of commissions, and had failed to inform IMR0 that investment business had been delegated to a firm which had dealing and compliance procedures which did not met IMRO’s standards.

All the investment managers undertook to make any necessary compensation to their customers, and to disclose commission paid to an associated broker. Substantial reviews of and revisions to internal procedures were also undertaken by the investment managers. Additionally, IMR as costs were borne by the investment managers.

Important Note: The above information is extracted from IMR0 Press Release 20/96 dated 29 August 1996 and SFC Press Release dated 29 August 1996.

Case No. 2:

Morgan Grenfell

In the Morgan Grenfell (UK) compliance failure it was alleged that certain unit trusts managed by Mr Peter Young included within their portfolios unquoted securities in excess of the limits permitted by the regulations.

Mr Young was an investment manager responsible for Morgan Grenfell’s unit trusts investing in European shares. At one stage the performance of these funds had out-performed — by a considerable margin — due mainly to a concentration in high-tech Scandinavian stocks which were unquoted. As these stocks fell out of favour with investors, fund performance dropped dramatically. Mr Young apparently maintained his holdings because he was convinced that eventually the investments would prove profitable.

Reportedly, Morgan Grenfell’s compliance monitoring identified that the funds’ holdings in unquoted securities had breached the 10% limit for such securities, but that no action was taken. The trustee of the funds appeared not to spot the breaches.

Rather than sell the illiquid unquoted securities at prices lower than those used to value units in the fund that held them (which would have reduced performance even further), it appears that a series of holding companies were set up to which the shares could be sold or transferred in exchange for shares or bonds in the holding companies. The holding companies were registered in Luxembourg and, although unquoted, their shares and bonds were issued so that they conformed with the definition in the unit trust regulations of an ‘approved security i.e. that they were issued in the last 12 months on terms that an application for listing would be made to an exchange or market, that the application had not been refused, and that the unit trust manager knew of no reason why the application should be refused.

The funds now held ‘approved securities’ whose assets comprised entirely unquoted securities. Mr Young therefore had appeared to comply with the letter of the regulation but not the spirit in that effectively he had exposed unit trusts to unquoted securities to an extent which was not deemed by the regulators to be appropriate.

Other allegations were:

(a) that the values of the unquoted securities in the unit price calculation and the values of the shares in the holding companies were overstated resulting in inflated and unrealistic unit prices (including the prices of other funds that derived their unit prices based on such prices)

(b) that as the unit trusts involved held more than 10% of the voting share capital or other share capital or convertible loan capital of certain of the companies in which the trusts invested, there was a breach of the regulations relating to the concentration of investments

(c) that the trusts invested in companies which fell outside the investment objectives of the trust as set out in the scheme particulars (prospectus) and promotional material of the funds

d) that some investments were made with the intention of benefiting Mr Young.

In reviewing the alleged breaches, one commentator raised the following questions in relation to the unit trust manager’s position. The regulatory position is that:

(e) the manager is solely responsible for calculating the value of units. In the case of unquoted securities the regulations require that the manager uses the best available market dealing offer or bid price, as appropriate, or if no price exists the manager’s reasonable estimate of a buyer’s or seller’s price.

(f) the manager is responsible for setting the investment objectives and strategy which appear in the scheme particulars and is responsible for managing the scheme in accordance therewith.

Against the catalogue of alleged breaches and the regulatory duties set out above, one must question the adequacy of the management controls at Morgan Grenfell. Fairly basic questions are:

(g) was there no committee of senior management to ensure that the investments which were detected matched up to the ‘house’ criteria?

(h) was there no list of approved investments for the ‘house?

(i) was there no vetting procedure for the acquisition of investments which were not on the ‘house’ list?

(j) did not the compliance department

(i) check to see that the investments all fell within the investment objectives?

(ii) check to ensure that the regulatory limits on unlisted securities were observed?

(iii) check to ensure that there was compliance with the regulation relating to concentration?

Given that it appears that is was known internally at Morgan Grenfell that certain regulations were breached, why was corrective action not taken?

(j) was there no senior investment expert overseeing Mr Youngs activities who would realise that the unlisted investments and investments in the Luxembourg holding companies were completely unknown and take steps to investigate their quality?

in connection with the establishment of the Luxembourg holding companies — were these set up by Mr Young? If so, did he have authority to sign applications for registration and was his authority checked by the Luxembourg authorities? Presumably there were registration fees and legal fees. How did Mr Young get authorisation to make these payments and did anyone question the reasons for the payments?

Important Note: The above information and comments are taken from Bankers

Trustee News, Issue 7, October 1996.

Suggested Answer to Activity

Activity 1

For which activity under s.212 of the CMSA is conducting ‘due diligence’ a defence?

Answer:

Section 214 makes it an offence to submit to the SC any false or misleading statement or information (including a material omission) or engage in conduct that is or may mislead or deceive the SC in relation to proposals primarily involving the issue or listing of securities.