CHAPTER 1

Learning Objectives

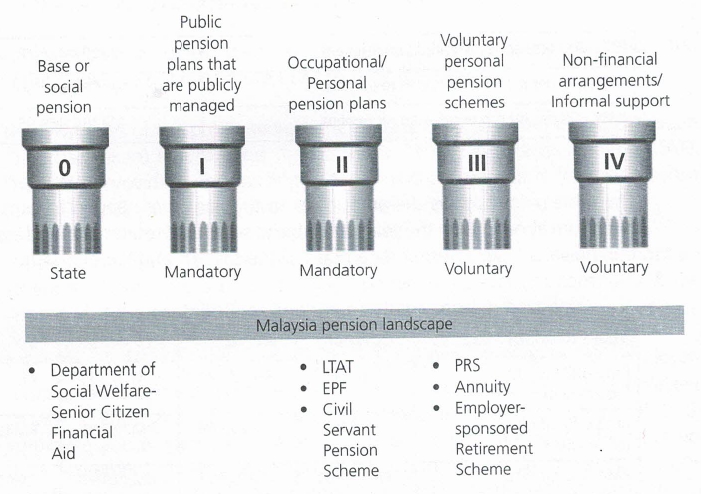

This chapter focuses on the basics of the Malaysian pension and retirement system, the World Bank’s multi-pillar pension framework and the need for Malaysia to develop the private pension industry.

At the end of this chapter, you should be able to:

(a) describe the current state of the Malaysian pension and retirement landscape and its key players;

(b) describe the World Bank’s five pillars framework for pensions and how it applies to the Malaysian context;

(c) give examples of the Schemes under the different pillars;

(d) recognise the need for higher retirement savings;

(e) explain the need to develop a private pension industry; and

(f) describe the benefits of the PRS.

1.1 THE THE MALAYSIAN PENSION AND RETIREMENT LANDSCAPE

The Malaysian pension and retirement landscape may be categorised along two distinct lines:

(a) public sector versus private sector pension schemes; and

(b) mandatory versus voluntary pension schemes.

Public sector and private sector schemes

Public sector schemes tend to be defined benefit plans in which the beneficiaries do not contribute at all to their retirement.

Two examples of the public sector schemes are the Kumpulan Wang Persaraan (Diperbadankan) (KWAP) and the Lembaga Tabung Angkatan Tentera (LTAT).

The KWAP provides pensions and other benefits for retired civil servants while the LTAT provides the same for retired armed forces personnel.

On the other hand, private sector schemes tend to be defined contribution schemes where there is a direct linkage between the amount contributed, the returns of these contributions and the resultant pension nest egg.

Two examples of private sector schemes are the EPF and the employer-sponsored retirement schemes. The EPF is governed by the Employees Provident Fund Act 1991 (EPF Act) and reflects the contributions of both employee and employers. The employer-sponsored retirement scheme refers to a retirement scheme established by a corporation in order to provide benefits to employees of that corporation or for its related corporation. It comes under the purview of section 150 of the Income Tax Act 1967 (Revised-1971) which provides a tax incentive for employers to contribute towards their employees’ retirement savings.

Mandatory and voluntary pension schemes

Mandatory pension schemes are retirement schemes that are mandated

by law. In Malaysia, all private sector employees have to participate in the EPF scheme by contributing a portion of their salary (currently the contribution is mandated at 11%) towards their retirement savings. The majority of these savings can only be withdrawn at the retirement age and the rest of the contribution can only be withdrawn under specific circumstances.

Voluntary pension schemes, as the name suggests, are retirement schemes that are voluntary and unlike the EPF, the minimum contributions to the voluntary schemes are not mandated by law. Currently, an example is the employer-sponsored retirement scheme. The purchase of annuities qualifies as voluntary schemes. The PRS initiative falls under this category.

(a) The adequacy of individual retirement savings

The average retiree in Malaysia faces the real issue of adequacy of retirement savings and whether these savings will last, given the uncertainty of life expectancy and capital erosion with inflation. The tables below illustrate the amount needed to sustain a suitable life-style post-retirement.

Amount of lump sum needed at the onset of retirement, assuming a life

expectancy of 20 years post retirement and an ability to invest the lump sum at 2% per annum:

RM2,000 per month required in retirement RM392,434.40

RM3,000 per month required in retirement RM588,651.60

RM4,000 per month required in retirement RM784,868.05

The table below shows the amount of savings per year needed to achieve the lump sum above, given the years available to save (until retirement) and assuming the individual can invest and compound the savings at 4% per annum:

So for example, an individual who is 40 years old and wants to retire in

15 years’ time with a retirement income of RM3,000 a month would need

to save RM29,398 a year, assuming he can invest this at 4% per annum over

the next 15 years while saving for retirement. Changing the variables such

as the time to accumulate the savings, the investment interest rates and the required retirement income would of course change the calculation but the crux of the matter is that there is a need for an individual to put aside a substantial amount of savings to achieve a post-retirement life-style that is acceptable.

Hence, there is a necessity to prepare an appropriate retirement savings plans so that the individual will have a sufficient nest egg come retirement. This nest egg should be made up of mandatory savings of the EPF and supplemented with voluntary schemes like the PRS. Both are necessary to ensure sufficient retirement savings. The EPF will provide the minimum savings and the PRS will help maintain a life-style that the retiree desires.

To determine the required income for the retiree, there is a need to understand the “income replacement ratio” which is the percentage of working income that an individual needs to maintain the same standard of living in retirement.

This ratio is usually between 60% and 90% of the working income before

retirement. A retiree who attains this replacement ratio through a combination of EPF withdrawal and current income through investments like the PRS and fixed deposits will be in a comfortable state come retirement.

(b) The World Bank’s Pension Conceptual Framework

(I) The five pillars framework

The World Bank’s policy framework applies a five pillar model when

evaluating a country’s pension and social security reform efforts. The

World Bank is of the view that a multi-pillar approach provides for

more flexibility and is therefore better able to address the needs of

the target segments of the population as well as provide a better safe

guard against any economic, political and demographic risks faced by a

specific pension system.

(ii) The five pillars in the Malaysian context

The following section conceptualises the World Bank multi-pillar

framework within the Malaysian context.

A non-contributory “pillar zero”

The World Bank sees this as a general social assistance financed and

provided by the local or national government to ensure people with low

lifetime income are basically cared for in their old age.

In Malaysia, the Social Welfare Department provides financial aid to

low-income citizens and this includes old age financial aid on a means

test basis.

A mandatory “first pillar”

This pillar aims to link contribution to varying degrees of earnings

with the objective of replacing some portion of lifetime pre-retirement

income. These defined benefit plans are usually financed on a pay-as-

you-go basis and subjected to demographic and political risk.

This pillar of the pension framework is not available in Malaysia but an

example of this “first pillar” would be in Japan where employees pay a

portion of their income to the national pension system which aims to

provide a “basic pension” to all residents in Japan. The basic pension

for the elderly is payable to a pensioner at the age of 65 if the person

has paid premiums for 25 years or longer.

This pillar is said to be subjected to demographic risks because, as our

example in Japan shows, the rapidly greying population puts enormous

strain on the funding. With fewer and fewer younger employees

to support the growing number of pensioners, there is a shortfall in

contributions to meet pension disbursements and there is considerable

pressure on the government to help fund the pension system.

A mandatory “second pillar”

This is typically an individual’s savings plan i.e. a defined contribution

plan where there are wide options in investment vehicles, investment

managers and withdrawal phase selections. Defined contribution

plans provide the individual with a clear link between contributions,

investment performance of the savings and end benefits.

In Malaysia, this pillar includes the EPF, the KWAP and the LTAT.

A voluntary “third pillar”

This pillar can take many forms (defined benefit or contribution plans,

individual savings plans) but it is essentially discretionary and flexible.

This third pillar’s flexibility compensates for the rigidity of the other

pillars and allows the individual to complement whatever is perceived

to be lacking in the individual’s retirement planning.

For Malaysia, this is where the PRS will feature. Other schemes under

this pillar include the private investment/saving schemes for individuals

(unit trusts, fixed deposits and insurance products), employer-sponsored

retirement scheme approved under section 150 of the Income Tax Act

1967 (Revised-1971), additional contributions to the EPF, annuities and

unfunded occupational gratuity scheme.

The PRS is being introduced to supplement EPF savings (for employed

persons) and other second pillar schemes. Although the EPF can be

considered an unqualified success with comprehensive coverage for

the employed sector and with healthy returns over the years in spite

of the global financial crisis, it is not mandatory for the self-employed.

Amongst the aims of PRS is to encourage this segment of the population

to start saving earnestly for their retirement.

Furthermore, studies have shown that most retirees exhaust their EPF

lump sum within three to five years of their retirement. This over-reliance on the EPF savings for their retirement needs is further exacerbated with leakages from their EPF savings with pre-retirement withdrawals for housing, healthcare and education. The PRS would encourage the pensioner to save more in an alternate source of scheme to provide diversity of income streams.

The PRS will also alleviate the concentration risk of the retirees who

have relied on one primary source for their retirement savings. The PRS

will provide an alternate source of fund management expertise and

one where members of the Scheme are ab[e to freely choose between

competing service providers.

A non-financial “fourth pillar”

The World Bank defines this as access to informal support such as

family financial support by the younger generation, other initiatives or

programmes such as universal healthcare, subsidised elderly housing/

retirement homes, home ownerships and availability of reverse

mortgages.

For Malaysia, this pillar relies mainly on traditional Asian values where

the young are expected to care for parents and elders.

(c) Key Players and Components

(i) Employees Provident Fund (FPF)

The EPF dominates the pension landscape in Malaysia. As at 31

December 2011, the EPF had a total of 13.15 million registered

members of which 6.26 million are active contributors and 487,664

active employers. (www.kwsp.gov.my)

The EPF is intended to help employees primarily save for retirement by

procuring a percentage of each member’s monthly salary and storing it

in a savings account. Employers also contribute a specific percentage

to the fund to meet their legal and moral obligation to safeguard and

enhance the members’ retirement savings.

Legally, the EPF is only obligated to provide a yearly dividend of

2.5% on the savings left in the member’s account but has historically

provided a higher dividend to the members although the dividends

have been declining on a trend basis because of the generally low

global interest rate environment. Unlike the net asset value (NAV)

for the PRS that will change every business day to reflect the latest

changes in the underlying fund assets, the amount of savings in the

EPF do not accrue any dividends until the dividends are declared by the

EPF. Most of the EPF savings are invested in Malaysian Government

Securities and other fixed income instruments (including private loans)

but investments in equities is allowed. Up to 20% of the EPF assets

can be invested overseas. The EPF members do have a choice of

some diversification if they participate in the EPF Members Investment

Scheme which allows the EPF members to invest 20% of the amount

in excess of the required basic savings in Account 1 with a unit trust

management company appointed by the Ministry of Finance.

The EPF is an occupational scheme and is tagged to employment

under the EPF. Thus persons who are self-employed would not

contribute to the EPF and would not benefit from mandatory savings

for retirement. With the current 11% employee and 12% employer

contributions to the EPF, an employed person saves at least 23% of

their salary each month with this scheme. Effective 1 January 2012,

the employer’s share contribution for monthly wages of RM5,000

and below increased 1% from 12% to 13%. Further, those who are

comfortable with the returns offered by the EPF (stable and higher than

fixed deposits) can opt to increase their contribution per month over

the mandatory rate of 11% by filling out a form with the EPF. This

“extra” contribution may not be tax exempt if the total contribution

amount is already above the tax relief limit.

Over time, in the absence of a viable alternative to EPF, individuals who

do not fall under the EPF would experience a significant difference

in their retirement savings. The PRS is introduced to encourage all

target groups including the self-employed to save more so as not to

be disadvantaged compared to those under the EPF although current EPF members are also encouraged to enrol in the PRS to supplement

their EPF savings if these savings in the EPF are insufficient to provide

for retirement. One thing to note is that the PRS and EPF contributions

are not inter-changeable. Once contributed, the amounts stay with the

respective Schemes and its Scheme rules. The PRS is also suitable for

any employer that wants to use it. The PRS is complementary to existing

mandatory provisions. Employers can use the PRS as an opportunity

to improve their recruitment appeal or employee value proposition to

attract employees.

The 1Malaysia Retirement Savings Scheme is akin to the PRS in that it

encourages those who are self-employed to contribute to a retirement

plan but through the EPF. Once the contribution goes into the EPF,

the self-employed will not have a say about the investments of their

contributions as per the other EPF members.

The EPF manages the fund both internally and externally through fund

managers. Unlike the PRS, the EPF members cannot select the asset

class, fund manager or the mix of funds for their contribution. There is

also no daily NAV calculation posted on the KWSP website because all

the contributions are commingled and a dividend is declared at the end

of the fiscal year. It is only then that the EPF member can assess the

performance of the fund and manager.

(ii) Kurnpulan Wang Persaraan (Diperbadankan) (KWAP)

The pension scheme for civil servants was established under the

Government Pension Ordinance of 1951 and applies to government

personnel that were eligible as of 12 April 1991. The pension scheme

is intended to provide financial security for retired civil servants by

paying them a monthly pension that reflects a percentage of their last

qualifying salary. The monthly pension benefit is no longer offered to

any civil servants after the date but the pension liability remains for

those who joined the civil service before the above date and needs to

be funded. The Pensions Trust Fund was established with the aim of

funding the pension liability in 1991 with a launching grant of RM500

million from the Government.

The KWAP was established on 1 March 2007 to replace the old

Pensions Trust Fund and receives a minimum of 17.5% of each civil

servant’s salary each month as contribution from the Government

towards financing its pension liability. There is no contribution at all

from the individual civil servant as it is a defined benefit plan. The

objective of the KWAP is to manage the fund towards achieving

optimum returns on its investments and shall be applied towards

assisting the Government in financing its pension liability.

(iii) Lembaga Tabung Angkatan Tentera (LTAT)

The LTAT was established in August 1972 by an Act of Parliament. The

main aim of the LTAT is to provide retirement and other benefits to

members of the armed forces (who are compulsory contributors) and

to enable officers and mobilised members of the volunteer forces in the

service to participate in a savings scheme. The secondary objective is

to promote socio-economic development and to provide welfare and

other benefits to retiring and retired personnel of the armed forces of

Malaysia.

Under the superannuation scheme, serving members of the armed

forces are required to contribute 10% of the monthly salary to the LTAT

and the Government being the employer will contribute 15%.

(iv) Employer-sponsored retirement schemes

As part of a broader corporate social responsibility as well as to

encourage employee loyalty, some employers have opted to provide

their employees with a pension that is usually funded by employer

contributions above the required EPF percentage. These plans need

to be approved and fall under section 150 of the Income Tax Act 1967

(Revised-1971). These contributions by the employers (usually tax

exempt up to a certain percentage — currently up to a maximum of

19%) vest immediately but can only be enjoyed at retirement in line

with the EPF savings. These schemes are usually managed in-house,

have a board of trustees with specific investment and withdrawal

rules and its funding is at the complete discretion of the employers.

These schemes are only open to the employees of the company or

group of companies. As mentioned earlier in the chapter, it is a

defined benefit plan for the benefit of the employees and not a

defined contribution plan like the PRS.

This employer-sponsored retirement scheme must be established

through a trust deed and rules of the fund, both of which must be

clearly expressed and both must also meet the strict requirements,

some of which are stipulated below:

(a) there must be alienation of contribution to the fund i.e. the

contributions made must be alienated from the contributors

and be held by a third party which is the board of trustees;

(b) payment of the retirement benefits can only be made when the

employee reaches the retirement age of 55, retires early due to

illness, dies or leaves Malaysia permanently; and

(c) the scheme is required to follow the investment policy laid

down by the IRB.

The possible losses suffered by these schemes during the recent

economic crisis and the high costs of administrating such schemes have

resulted in many employers opting to migrate their scheme to the EPF.

(v) Annuities

In an effort to encourage more retirement income, the public can take

advantage of the tax incentives under the tax law to buy annuities

offered by insurance companies. These annuities are contracts

whereby the annuitant (the person who buys the annuity) receives

a series of fixed payments at regular intervals (usually monthly) from

the insurers until the death of the annuitant. Each annuity payment

represents the repayment of a portion of the purchase price plus interest

earned.

The purchase price may be done at one go (a lump sum payment)

or more likely in the context of saving for retirement, paid monthly/

annually over the working tenure of a person. Contributions must

continue until the price of the annuity is paid or the annuity may not

provide the annuitant with the desired payment (after all, the annuity

functions on the total contributions and stopped contribution disrupts

the workings) at retirement. If an annuity is cancelled the annuitant

may get back the contribution less administrative and other charges

and the person will have to start all over again later if he wants to buy

another annuity.

(vi) Conclusion

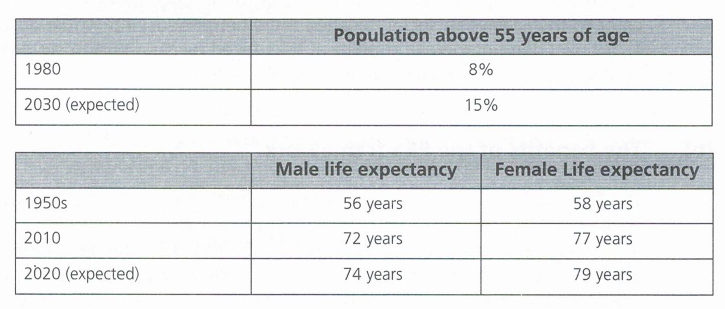

The current retirement landscape in Malaysia cannot fully address the

needs of retiring Malaysians. Although the second pillar mandatory

savings has provided the basis for retirement planning, solely relying

on it would not be adequate to maintain a comfortable lifestyle post

retirement. The traditional fourth pillar which relies on the young to

care for the elderly would only work in a society where there are many

to support the few. In an increasingly greying/ageing population like

Malaysia, the number of elderly will increase exponentially with time

and the burden on the fewer young people will be enormous. There is

an impetus to find a self-sufficient solution.

Hence, there is the need to develop the third pillar of voluntary

savings. The government’s initiative to promote the PRS through

tax incentives highlights the urgency and the importance to get the

populace to think about their own retirement needs. With a national

focus on more voluntary savings, the PRS is the platform to kick-start

this initiative by providing a universal, flexible and tailored solution to the individual.

1.2 THE OBJECTIVES AND BENEFITS OF THE PRS

(a) The need for retirement protection

Like the rest of the world, Malaysia will also be, in the coming years, experiencing a rapidly ageing population.

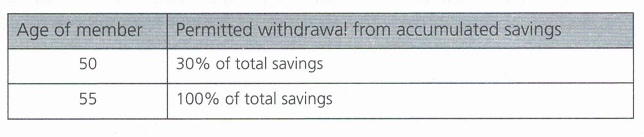

The longevity risk has posed a great challenge to the adequacy of savings for retirement. This is further compounded by premature exhaustion of retirement savings in the early period of retirement, in view of the prevailing practice of lump sum withdrawal of the EPF contributions at the age of 55 and greater demands for a lifestyle post retirement that mirrors that currently existing. This naturally necessitates an overall higher amount of savings to address this situation of funding one’s lifestyle in the retirement phase. Furthermore, there is statistical evidence to suggest that the current amount of savings under the EPF and other schemes under the mandatory “second pillar” is insuffident to last a retiree long into their retirement (with some studies showing that most run out of money within 10 years of their retirement). This is more so when the saver is wholly reliant on the EPF savings as the sole basis f retirement income and there is no alternate source of savings to supplement that income.

To address this problem, four solution are possible

Firstly, Malaysia is exploring whether to raise the mandatory retirement age which will allow a longer period for the employed to accumulate savings. Furthermore, with medical advances people are healthier and can work productively up to an older age.

Secondly, it can increase the mandatory contribution rate under the “second pillar”. This is not ideal as it puts an unnecessary strain on employers and increases the cost of doing business and can make Malaysia uncompetitive in the effort to attract and retain talent. Furthermore, this solution is not universal as only employees who are covered under the EPF or other “second pillar” schemes would benefit.

Thirdly, it can consider raising the minimum wage over time if productivity allows so that the workers can benefit from a higher level of wages and hence savings both through the mandatory EPF and other voluntary schemes.

Lastly, it can develop a voluntary retirement scheme under the “third pillar” in order to expand the range of retirement schemes, expand coverage on a voluntary basis to all segments of the population and improve the adequacy of retirement savings overall. Having a robust multi-pillar pension system would cater to the Malaysian society’s varied retirement needs and would absorb the economic, demographic and political risks faced by the pension systems. The implementation of the PRS comes under this solution.

(b) The benefits of the PRS framework

The PRS addresses the coverage issue as it helps those who do not save now under the EPF, like the self-employed. The adequacy of retirement savings is also tackled by the additional savings through the PRS Scheme. Additional or voluntary employer contributions add to the adequacy solution. Lastly, the PRS is sustainable as in terms of monthly deductions, a person need only save an additional RM250 per month to enjoy the full tax relief where a person earns a basic salary of above RM4,500.

(i) PRS is a transparent investment vehicle

The Scheme is generally a transparent investment vehicle where the

following information is disclosed upfront:

(a) all fees and charges (direct and indirect);

(b) investment mandate including investment objectives and

strategy, investment limits and asset allocation;

(c) fund performance; and

(d) publication of annual reports as well as choice of PRS Providers

and PRS funds within each scheme.

Any changes to the investment objectives or fees require the approval

of the PRS members while some other less material changes require

a supplementary disclosure document to be lodged. The portability

feature of the PRS supports transparency as members need information

PRS Providers.

(ii) Provide a pool of funds to fund retirees during retirement phase

This universal and inclusive effort would encourage Malaysians to

save more for their retirement by becoming a self-funding retiree.

Furthermore, the PRS framework will allow individuals the flexibility to

choose from various providers and funds offered. The PRS is portable

whereby contributions made and accrued to the PRS members can be transferred to another provider. The portability feature (which we will

discuss under Chapter 4 Features of the PRS) also encourages good

performance that will benefit the PRS participant. Over the long term,

this should result in better long-term returns and a higher amount

of savings available at retirement, provided investments in the fund

performs as expected.

If the retiree managed to build up sufficient savings (both through

contribution and investment performance) in the PRS during the

employment/savings phase of the retiree, then the yearly returns of the

PRS during the retirement phase will enable the retiree to supplement

a portion of the living expenses during retirement. Coupled with a ,

drawdown in accumulated wealth (the EPF savings) and other incomes

(e.g. allowance from children, interest from savings), the retiree will be

able to live a comfortable lifestyle.

(iii) Additional source of long-term capital for economic growth

While maintaining the primary aim of increasing retirement savings

for individuals so as to fund their retirement needs during old age,

the PRS has ancillary benefits of unlocking savings as Malaysians have

a high savings rate by international standards. This unlocked savings

could be channelled to create new and sustainable fund flow to spur

economic growth and growth in the capital markets in particular. This

helps the member directly as robust growth in the capital-markets may

attract talented fund managers who will manage the PRS effectively

to help the member achieve his long-term return goals. The strong

growth in the financial sector will also not be isolated and will spill over to other sectors thereby increasing wage levels and quality of life. When the members help the capital markets, they actually help themselves in a virtuous cycle.

(iv) Benefits to the Malaysian capital market

These sustained fund flows from the PRS will increase vibrancy in the

capital markets and yield benefits, including:

(a) increased product innovation and competition;

(b) increased activities and skill sets of the intermediaries;

(c) building scale in the fund management industry; and

(d) attracting more institutional investors which in turn improve

market performance and foster good corporate governance.

(v) Reduce the burden on Government finances

A vibrant PRS and other “third pillar” schemes guided by the World

Bank’s multi-pillar approach would reduce the need for the Government

to provide a social safety net for the population in retirement phase.

(c) “Third pillar” experiences in other countries

The PRS is an example of the “third pillar” under the World Bank’s framework. This third pillar scheme helps the members to voluntarily save more for their own retirement needs. The implemention of “third pillar” schemes is varied but generally the issues of an ageing population and sustainable retirement, need to be addressed promptly and many governments around the world are doing just that.

Some of the examples of implemented schemes are:

KiwiSaver in New Zealand

This scheme started out as ,a voluntary long-term savings scheme and came about in July 2007. It is aimed at improving the low average rate of saving. Employee participants can chose to contribute 2%, 4% or 8% of their gross pay with a lot of flexibility to change contribution rates or scheme providers. The self-employed can choose how much they want to contribute. There are some tax benefits to the scheme to encourage participation. There were 1.6 million Kiwi Savers as at June 2011 with total contribution of NZ$1.6 billion.

Supplementary retirement scheme in Singapore

The supplementary retirement scheme (SRS) is part of the Singapore

government’s multi-prong strategy to address the financial needs of a greying population. Contributions to the SRS are voluntary and are eligible for tax relief. Investment returns are accumulated tax-free and only 50% of the withdrawals from the SRS are taxable at retirement. The annual SRS contribution cap (currently at S$12,750 for Singaporeans and permanent residents and S$29,750 for foreigners) is subject to review. As at 31 December 2010, the total SRS contributions amounted to S$2.49 billion.

Assessment Questions

Question 1

In the context of the World Bank Pension Conceptual Framework, the Private

Retirement Scheme would fall under the _______________.

(A) “first pillar”

(B) “second pillar”

(C) “third pillar”

(D) “fourth pillar”

[Answer: C]

Question 2

What are some of the cited benefits from the Private Retirement Scheme?

I. Reduce the need for Malaysians to invest in unit trusts

II. Additional source of long term capital for economic growth

III. Improve the living standards of Malaysians at their retirement

IV. Increase the fiscal burden of the Government to provide a social safety net

(A) I and IV only

(B) I and III only

(C) II and III only

(D) II, III and IV only

[Answer: C]

Question 2

Which of the following statements are TRUE in relation to the Private Retirement Scheme?

I. It is mandated by law

II. It is a voluntary pension scheme

III. It is a defined benefit plan

IV. It is a defined contribution plan

(A) I and III only

(B) I and (IV only

(C) II and III only

(D) II and IV only

[Answer: (D]